Image: Screenshot, Reuters

How They Did It: The Pulitzer Prize-Winning Series Exposing Fentanyl’s Global Supply Routes

Read this article in

Fentanyl, a powerful opioid 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, has flooded illegal markets since 2013. The effects have been devastating: synthetic opioid overdoses, largely driven by fentanyl, have claimed tens of thousands of lives each year, peaking at 110,000 deaths in the US in 2022. The drug is relatively easy to produce and can be made entirely in a lab using a few essential chemicals known as “precursors.” But it’s difficult for US regulators to prevent the creation of fentanyl simply by banning precursors, because new or different combinations of these chemicals are created faster than regulations can take effect.

To show the business of fentanyl production in the US today, a team of Reuters investigators led by Maurice Tamman, the editor-in-charge of computational and forensic journalism, pitched an audacious idea: the team would legally purchase the precursor chemicals needed to fully create fentanyl and have them shipped to New York and Mexico City using international carries such as FedEx. Over the course of their reporting, they succeeded in purchasing enough precursor materials to create up to $3 million worth of fentanyl tablets for little more than US$3,600 in bitcoin, mostly from international sellers based in China.

Their resulting seven-part investigative series, Fentanyl Express, revealed just how easily chemicals used to create fentanyl can be acquired, and was recently awarded the 2025 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting.

GIJN spoke to Tamman, Reuters correspondent Laura Gottesdiener, and Stephen Eisenhammer, Reuters’ Bureau Chief for Mexico and Central America, to walk through how they reported the story.

Acquiring the Precursors

Coming off an investigation that tracked the smuggling of electronics into Russia to make weapons for its invasion of Ukraine, Tamman considered using a similar approach to track import-export data in Mexico — a country at the heart of the international fentanyl trade due to the role of Mexican organized crime in producing and trafficking illegal fentanyl.

But that strategy hit a dead end, so the team pivoted to contact the overseas sellers directly. “What I was working on at the time was trying to understand, essentially, the formula. How are these things advertised? What are the kinds of chemicals we really wanted to get? Which ones could we legally get? Which was a lot of understanding the different regulations in different countries,” Gottesdiener explains.

They decided to try legally purchasing chemicals originating from Chinese companies that had been indicted by the US Department of Justice for their role in the fentanyl trade. “We thought, if we can test what impact these indictments make by contacting the companies that had been indicted and seeing if they would still be willing to sell fentanyl precursor chemicals, either to the United States or Mexico,” he adds.

The team quickly found that these chemicals could easily be found on the public internet, on social media, Google Image Search, and even Soundcloud. From there, it was a matter of contacting the sellers, which was done through encrypted messaging platforms like Signal.

“These relationships we developed with these sellers were pretty dynamic and kind of curious,” Tamman says. “They are at once flirty and friendly, but also completely agnostic as to why we were getting this stuff. They didn’t ask questions. They had no curiosity about what the purpose was, although they were clearly advertising these chemicals for the purposes of making fentanyl.”

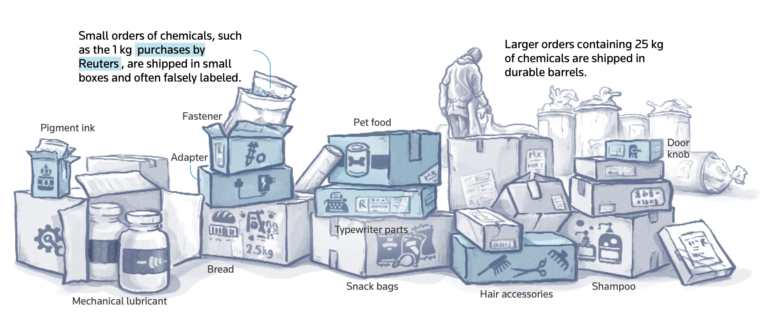

Ultimately, the team was able to acquire 11 of the 12 precursor chemicals needed to create fentanyl from seven separate Chinese suppliers (the 12th chemical was acquired through an order from a US chemical company via Amazon), purchasing them through transactions made through the difficult-to-track blockchain currency bitcoin.

By forming consistent relationships over the course of a year with sellers — including landing multiple buys from the same sellers — the team was able to see how dynamic the fentanyl industry was.

“At the very beginning of the project, they [the sellers] would offer you a very straight pre-precursor for [the key fentanyl chemical compound] piperidine, for example. Six, nine months later, they were not hawking those anymore. They were hawking variations of those because they were trying to get around regulation,” Gottesdiener explains. “So by continuing to talk with these people, buy from these people, we were able to sort of see just this tiny snapshot about how their market was evolving.”

Importing the Chemicals

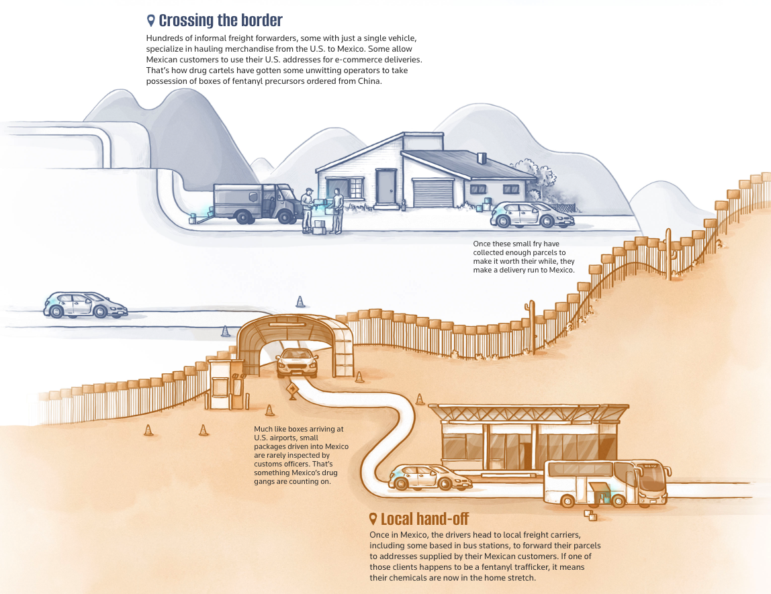

The fentanyl trade is embedded in the global supply chain. As many precursor chemicals are legal and used for legitimate means, such as in pharmaceuticals and perfumes, the team found it easy to import the chemicals into the US, including through carrier services like FedEx. In total, 14 chemical deliveries were made, including six to Mexico City, seven to a mailbox in New Jersey, and one to an apartment in New York City.

The diversity in delivery locations was intentional. “There has been — and continues to be, to some extent — a fairly simplistic narrative from some areas of government and law enforcement, that this stuff all just comes in and is produced in Mexico and is then consumed in the US, a very kind of binary narrative,” Eisenhammer said. “We really wanted to show that it’s not as simple as that, that these supply chains are incredibly complicated and actually the US plays a pretty important role.”

The Reuters team’s reporting showed that the US plays a key link in the supply chain of providing fentanyl precursors to illegal drug manufacturers in Mexico. Image: Screenshot, Reuters

Tamman adds: “By making that choice to try and ship it into the states as well as into Mexico, we opened up an avenue of reporting that we probably hadn’t anticipated.”

In at least two situations, the team found gaps in US regulations and customs enforcement. In one case, a package containing a precursor chemical mislabeled by the seller as “ink” was held by FedEx until an updated form could be provided by the team. On advice of their legal team, the team filled out an updated form that correctly identified the chemical being shipped, and the package was subsequently waved through. In another situation, a package containing a precursor chemical was searched by US customs, but was still permitted to enter the country without issue.

“Clearly they looked at it and they said — this chemical, this package is suspect, but they opened it up, they resealed it, and they sent it along its way, so it arrived. No problems, right? And it’s remarkable to me that that was allowed to happen,” Tamman says.

After acquiring the chemicals, there was one more step: verifying that the chemicals they received could, in fact, be used for fentanyl. To do so, they approached a chemist at the Center for Forensic Science Research and Education, who identified the chemicals as fentanyl precursors, as well as one unidentified chemical that later proved to be a little-known “designer precursor” not on the list of US-regulated chemicals.

The team did not make fentanyl with the chemicals, and ensured the chemicals were safely destroyed after identification.

Fentanyl precursors were shipped from China in a variety of container sizes, and some were mislabeled to avoid detection. But other suspicious packages were flagged by customs officials and searched yet still allowed to proceed for delivery. Image: Screenshot, Reuters

Safety, Legal, and Ethical Considerations

The team wanted to ensure that every transaction, and every chemical imported, was legal according to US and Mexican law — not just for their own ethical and legal reasons, but to show how easily fentanyl ingredients could be obtained.

“We thought about where we have the chemical sent to, then the legal concerns were also really significant, and involved a lot of research here in Mexico… around what things were banned, what wasn’t banned, what chemicals we could buy, what we couldn’t buy,” Eisenhammer explains. “We also have in-house lawyers who went through all of this with a pretty fine-toothed comb.”

During their reporting, laws in the US and Mexico were updated to target different precursor chemicals, so the team had to be continually aware of what was currently legal to buy and import.

“One of the things that the lawyers stressed when we were doing the reporting was that you could not ask the sellers to do anything illegal,” he says. “If there was anything around mislabeling, or how they were going to get the stuff into Mexico, they [the sellers] had to do that entirely of their own accord.”

The team also maintained strict security protocols throughout the investigation. To contact sellers, journalists used burner phones, burner SIM cards, and even a burner laptop, and used end-to-end encrypted platforms like Signal and WhatsApp to communicate with sellers.

The team was also careful about personal security, and took precautions against inadvertently provoking cartels or drug traffickers during their transactions. “Mexico has a terrible reputation for attacks on journalists, murders of journalists, and so that was something we took incredibly seriously,” Eisenhammer points out.

Follow-up Investigations

The Reuters team wasn’t able to uncover every aspect of the transnational fentanyl trade. “Reuters couldn’t determine whether any of the Chinese suppliers were the actual manufacturers of the chemicals received or simply middlemen. Nor could the news organization determine where the operations were located. Reporters could dig up nothing more than phone numbers for two of the sellers. For the others, corporate websites and Chinese business-registry documents yielded addresses,” the article states.

Reuters did send reporters to one of the locations listed — an office tower in Wuhan, China — where a seller, Hubei Amarvel Biotec, was registered, but was told by the building’s management that the company did not rent a space there. Nevertheless, the team found it important to follow up on the lead: “Just because they’re in China doesn’t change how we go about doing our reporting. We had an address for these outfits, and we certainly wanted to see whether or not they were legitimate, if there was somebody there who could talk to us,” Tamman says.

While the investigation helped illuminate the nature of the global fentanyl trade, many questions remain unanswered that could prompt future investigations. “I think we did break new ground with it, and did get closer to understanding the supply chain than anyone has done before, but we didn’t get all the way,” Eisenhammer says. “Where were they [the sellers] getting these chemicals from, and where were they producing them? Were they getting them from someone else? Those were questions that we weren’t really able to answer.”

For investigative reporters looking to dig into big, front-page stories like fentanyl, looking for unique angles is key, Tamman says. “You have to think about reporting in ways or approaches to stories that cannot be replicated,” he adds.

But Gottesdiener also notes that even criminal networks or drug rings share similarities with legitimate businesses: “Remember always that it is a market governed by logical financial interest, and there’s always going to be a reason, a logical reason, that crime groups are doing the things they’re doing.”

Devin Windelspecht is a Washington DC-based writer and editor with a passion for solving pressing global problems through journalism. His writing highlights the work of independent journalists covering some of the most pressing topics of today, including conflict, human rights, climate change and democracy. His reporting has highlighted the work of pro-democracy reporters in Russia, environmental reporters in Brazil, journalists covering reproductive rights in the US, war correspondents in Ukraine, and exiled media outlets covering authoritarian countries around the world.

Devin Windelspecht is a Washington DC-based writer and editor with a passion for solving pressing global problems through journalism. His writing highlights the work of independent journalists covering some of the most pressing topics of today, including conflict, human rights, climate change and democracy. His reporting has highlighted the work of pro-democracy reporters in Russia, environmental reporters in Brazil, journalists covering reproductive rights in the US, war correspondents in Ukraine, and exiled media outlets covering authoritarian countries around the world.