Investigative Tips for Following the Cryptocurrency Trail

Read this article in

There is one key reason why reporters should start learning about cryptocurrencies, says Jan Strozyk, data editor at the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). “The people that [journalists] investigate will also be interested in these things – and will use them – and so you should know about them,” he told GIJN after a panel at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia, Italy.

A lack of regulatory oversight of cryptocurrencies like bitcoin, he says, plus the anonymity that they offer, makes them “very interesting” for organized crime figures and cyber thieves. Understanding cryptocurrencies may involve learning a new financial language, as well as exploring a parallel financial system favored by everyone from investors to anarchists. But experts say there are ways to investigate this murky topic that can reap rich rewards for reporters asking the right questions.

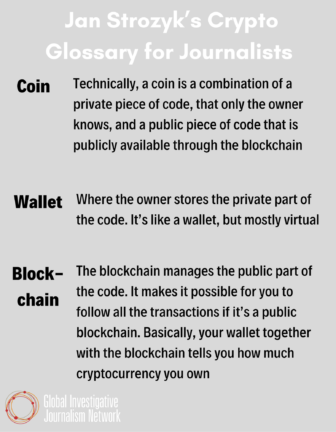

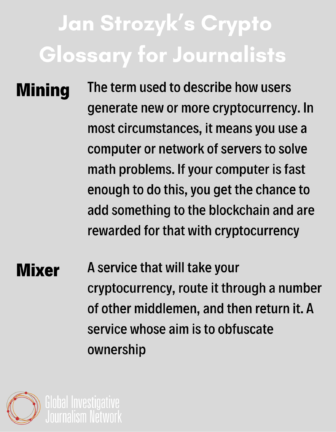

First, says Strozyk, journalists need to know what they are talking about. (For more on cryptocurrency terms, see Strozyk’s glossary for journalists at the end of this story.) Here he provides a quick primer for the uninitiated:

Q: What are cryptocurrencies?

Strozyk: Cryptocurrency is a term that describes, basically, virtual currencies that you can use for payments on the internet. Technically, you can use it also offline, but mostly it refers to pieces of code that can be used like you would use a coin or a bill or any other form of payment.

Q: How do they differ from normal money?

Strozyk: Cryptocurrencies have a few advantages over regular money and regular transactions and one of them is that you can make these payments and you don’t necessarily have to reveal who you are. With a bank transaction, if you go open a bank account the bank will need to see your identification card, they will probably also ask you for what you need the money for. If you put a lot of money into your bank account they will probably ask you where it comes from. Since cryptocurrencies work a little bit differently technically — and there’s no single authority over them — there’s no bank-like thing that controls these transactions. Nobody’s going to ask you for anything.

Q: Who is interested in that?

Strozyk: That makes them very interesting for a group that most reporters are also interested in, and that is organized crime figures or cybercriminals that use them in their schemes.

Following the Money

Ana Poenariu, an investigative journalist with the nonprofit RISE Project Romania and OCCRP, also spoke at the Perugia panel. She says the anonymity factor is a particular draw to those engaging in illegal activity: “Every criminal believes if they are using cryptocurrency, they are hiding.”

To some extent, these bad actors are right to think this way, Strozyk says. There are inherent difficulties in tying individuals to particular cryptocurrency wallets – or proving that a multi-million dollar transfer was, for example, made by a particular person. “As an investigative reporter you have the chance to figure out who owns a [traditional] bank account because there’s a direct connection,” he notes. “You have the chance to find a bulletproof chain of documents that links a person to a bank account. It’s really, really hard to do the same for a cryptocurrency wallet.”

However, cryptocurrencies do offer investigators something else, Strozyk adds. The blockchain, a decentralized and public ledger that contains every transaction for a particular cryptocurrency, can contain important information. So for bitcoin, currently the largest cryptocurrency, the blockchain gives you information such as when a particular bitcoin was bought, or sold, and for how much. That, Strozyk notes, makes for rich financial digging when you know what you are looking for. “That’s what I mean by it’s transparent, it’s traceable,” he says.

Perhaps the most famous bitcoin transaction tells the now-sorry tale of a man who, in 2010, bought two pizzas using 10,000 bitcoins. At the time, those coins were only worth about $40. But if he’d held onto them, today they would be worth hundreds of millions of dollars. That disastrous exchange could in theory still be found in the publicly available cryptocurrency data.

Since bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are not backed by governments or central banks, these wild swings in value are not uncommon. A huge surge in popularity of the currency created bitcoin millionaires. But a steep drop in its recent valuation subsequently wiped out a number of them. Volatility seems par for the course. The chairman of the US Securities and Exchange Commission, Gary Gensler, has compared the cryptocurrency market to the Wild West, calling it a system “rife with fraud, scams, and abuse.”

A bitcoin cryptocurrency mining operation, or crypto farm. The mining process consumes a great deal of electricity. Image: Shutterstock

While many users of cryptocurrencies are ordinary people and investors, it’s also a financial system popular with those seeking to mask their financial dealings.

Hakan Tanriverdi, who is with German public broadcaster Bayerischer Rundfunk, worked on a story that allegedly identified a ransomware millionaire by investigating cryptocurrency transactions and social media profiles. That investigation began with the ransom note and worked backwards.

“This is what ransomware is: somebody hacks your company’s network, they are able to encrypt all the data,” Tanriverdi told reporters in Perugia. “Your PDFs don’t work. Your pictures won’t show up. Your [document] files won’t work. The one thing that is working is a ransomnote.txt file. If you open it, it’s a message from the hackers: ‘You have been hacked. If you want to get your data back, this is how you can reach us.’”

But since these ransomware hackers are trying to get as much money as possible from as many companies as possible, Tanriverdi says they still have to make it “easy” to pay. “That also means that the hackers are going to give away all the information needed to get in touch with them in the same file they are hacking the company with,” he explains. “Everything you need to know is in the file.”

In Tanriverdi’s case, that involved investigating the ransomware note and tying the digital ID of a cryptocurrency wallet to a real person. The reporting team believes they found a core member of a ransomware group identified by the US Treasury as one of 10 malware groups potentially behind $5.2 billion in illicit bitcoin transactions.

Investigative Tools

While the chase can be complicated in the crypto space, Strozyk says there are a number of tools out there to help reporters.

- The networking diagram tool neo4J: “Someone wrote a script where you can import the blockchain and run all types of analysis on it,” he says.

- Learn me a bitcoin: “It’s a fantastic website, an analysis tool where you can type in addresses and transaction ID’s and you can figure out who sent money to whom. That’s the basic thing, but it has a lot of documentation around working with bitcoin working with the blockchain as well,” he notes.

- Blockchain.com: Reporters can use this to study historical data about cryptocurrency wallets. “The blockchain is basically a very, very, very long list that contains all the transactions,” Strozyk says, “and there are some tools out there that help you analyze the blockchain and figure out who sent money to whom, which address sent money to which other address.”

- Elliptic: “At OCCRP we use this,” he explains. “It’s a paid tool, where you can do these nice visuals, clustering. What Elliptic does is it scans the internet for ransomware actors — for hackers, for cybercriminals of all sorts — and then it would basically tag wallets so you can figure out if a wallet was used in a crime before. If someone gets a lot of money from a wallet that was in a crime, it’s highly likely that this person is also involved in the crime as well, or in sorts of cybercrimes.”

- Aleph: Strozyk adds that OCCRP’s database toolkit Aleph also has some cryptocurrency digging capabilities, and journalists can sign up for free access. “With this, you can find from leaks or other sources how cryptocurrencies link to email, which is a good step if you want to find out who is behind a wallet,” he says.

- Whale Alert: This tool is a Twitter account that sends an alert when someone makes a big transaction. Strozyk pointed to an example from the day before the Perugia panel where someone sent $178 million in bitcoin “from somewhere to somewhere: You can click the link and start investigating from there,” he says.

From left to right: OCCRP’s Jan Strozyk, RISE Project Romania’s Ana Poenariu, and Bayerischer Rundfunk’s Hakan Tanriverdi spoke at a panel on investigating cryptocurrency. Image: Naima Bettinsoli/ International Journalism Festival. Published under a Creative Commons license.

Following the Trail — And Why It Matters

For many years, Poenariu thought that the easiest way for criminals and organized crime figures to wash money was through real estate. “But I was wrong,” she says. “The easiest way to wash money is also through bitcoin. The thieves evolved.”

As our lives have gone digital, so too have the methods of the groups who want your assets, explains Poenariu, who has worked on several cross-border investigations, including the award-winning Riviera Maya Gang series. And those trading in online currencies often profit from a chronic lack of legislative oversight. While bitcoin was created in 2009, the first crypto confiscation by law enforcement in her home country of Romania wasn’t until 2020, she notes.

“Our authorities are a little bit late, meaning cryptocurrencies are used not only for money laundering but for getting card data, also for drug trafficking,” she points out. Poenariu, who has also gone undercover to buy cryptocurrency from a crypto farm believed to be linked to organized crime, says there are some key areas journalists can investigate to find out what is happening in this area in their countries.

- Trace the equipment linked to crypto. “One of the things I discovered can be done is to follow the hardware – here I’m talking about mining,” she says, speaking about the process by which miners lend their computing power to verify cryptocurrency transactions and to create new cryptocurrency tokens. But for this, miners need equipment. “In order to mine and bring new crypto to the market you have to have hardware. This can be bought online or on eBay, but if it gets into a country you have trading data.”

- Track blackouts and spiraling power use. “Another important thing is to check electricity consumption: Ask yourself in your country or city, who is the biggest electricity consumer?’” she says. “In order to mine [cryptocurrency], you need big, big amounts of power. Think about: Who are the electricity providers? Where do you get this type of data?” A number of countries have banned crypto mining, with countries like Kosovo and Iran citing the strain it can put on domestic power grids, and Poenariu says power cuts can be a clue for starting an investigation.

- Fieldwork is still key. “Track exchanges and cryptocurrency ATMs [which are rare, but do exist]. These exchanges can have two forms: online, where you have to identify yourself with an ID card and email; or a physical one, which is like going to an office and exchanging crypto like you exchange euros or dollars,” she explains. “Go to where the ATM is to observe what’s happening there. Are there cameras nearby? Of course, we also rely on human sources, is there someone working for an exchange or in law enforcement?”

- Lastly, she advises reporters to check if there have been court decisions in their countries that detail bitcoin or other cryptocurrency transactions. In 2014, she states there were only two court cases in Romania that included this information. But since then, there have been 345 rulings that involve cryptocurrency data and nearly 90% of these cases involve criminality. “Everything bad that you think of that can be done in this world you can find in these court decisions,” she says.

Ignoring a modus operandi favored by criminals and bad actors, Strozyk suggests, is like trying to solve a puzzle with only some of the pieces. “I think it’s a tool that’s used mostly, honestly, by criminals,” he says. “Since we as investigative reporters are interested in these criminals, it’s something that we need to know about.”

Additional Resources

Reporter’s Guide to Investigating Organized Crime: Cybercrime

Tracking Illegal Funding Campaigns via Cryptocurrency

GIJC21: The New Organized Crime

Laura Dixon is GIJN’s associate editor and a freelance journalist from the UK. She has reported from Colombia, the US, and Mexico, and her work has been published by The Times, The Washington Post, and The Atlantic. She has received reporting fellowships from the International Women’s Media Foundation and the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting.

Laura Dixon is GIJN’s associate editor and a freelance journalist from the UK. She has reported from Colombia, the US, and Mexico, and her work has been published by The Times, The Washington Post, and The Atlantic. She has received reporting fellowships from the International Women’s Media Foundation and the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting.