Calculating Corruption: Peru’s Ojo Público Creates Tool to Gauge Contracting Risks

Read this article in

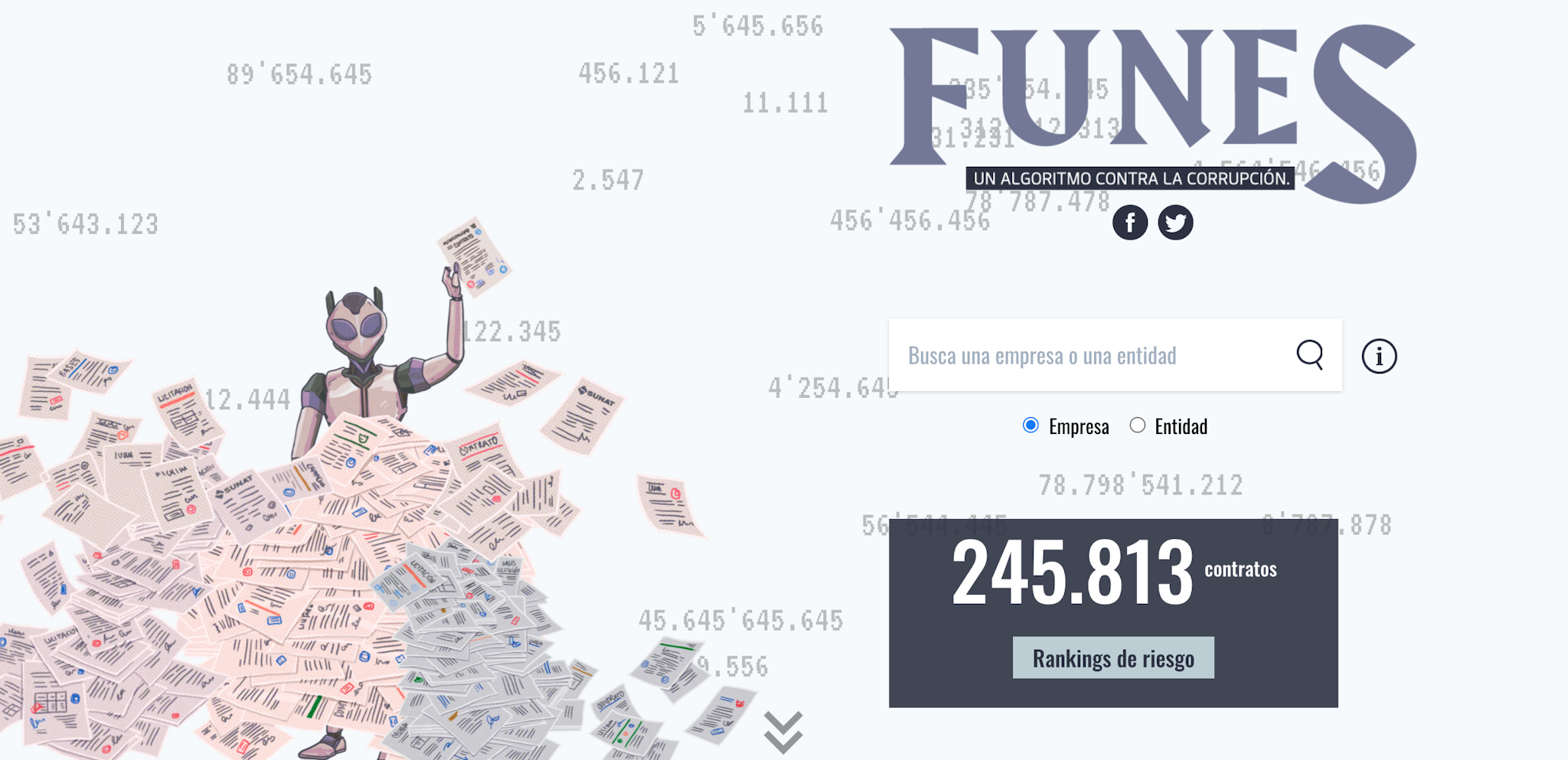

Image: Open Contracting PartnershipFUNES, a tool created by the Peruvian news outlet Ojo Público to investigate government contracts, is a website, a search engine, and a repository of more than 245,000 public contracts. Simply enter the name of a company or entity, and in the blink of an eye, an algorithm checks hundreds of documents and calculates the corruption risk as a percentage.

FUNES has already played a key part in many of Ojo Público’s investigations. In 2019, for example, the outlet revealed that the main milk supplier in Peru was the sole bidder for 90% of the contracts it obtained and that the government had paid the same organization more than US$70 million.

The platform took a team of close to a dozen people more than a year to create. With the support of a grant from the ALTEC initiative, journalists, programmers, and specialists in statistics and law formed a multidisciplinary team with a clear objective: to investigate the public procurement system in Peru in a more systematic way. In 2020, the tool won first place in the “Innovation” category of the Sigma Awards, the most prestigious prize in data journalism.

Why the name? “Funes the Memorious” is the protagonist of a short story by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges whose character had the so-called sage syndrome: the ability to remember everything down to the smallest detail. This is the spirit of the algorithm. An instrument to read thousands of documents and detect signs of “collusive” corruption: instances in which a public official is linked to a company and uses their power and influence to win a public tender.

The FUNES algorithm is unique. It is based on a methodology developed by Mihály Fazekas, an assistant professor on big data at the Central European University, and which proposes a definition of corruption according to certain indicators. More than 20 parameters, each carrying a certain weight, are used to calculate the corruption risk of a company in a few seconds.

The tool draws on four databases containing more than 245,000 documents. It analyzes records of public contracts, electoral campaign contributions, lists of suppliers, and even the official gazette. When the calculation is complete, the alerts or “red flags” allow Ojo Público to tell stories that expose cases of corruption that promote change.

Ernesto Cabral, one of the journalists in charge of the project, said that FUNES not only helps to shorten the time it takes to conduct an investigation, but it also gives a better overview of the contracting system by combining different databases. Nelly Luna, co-founder and editor-in-chief of Ojo Público, said that FUNES is much more than a tool for journalists, it allows people to “exercise greater citizen control.”

Behind the Scenes of the Project

But the project did not happen overnight. The information used by the tool is the result of years of searching for data, cleaning it, and assembling public databases that were not readily available. “When we asked the departments for access to their information, they told us that it was on the website, but they only had general search engines and the databases we were looking for weren’t there,” Cabral said.

This led the team to create scripts to download the data that the government sites did not show and that was critical to the newsroom’s investigations. However, the process for obtaining information on public contracts was even more complicated: “With the body that supervises government contracting, we had more difficulties because when they detected our IP, they blocked it. That was the most difficult [part],” Cabral said.

Organizing and cleaning the data was another challenge. Although the team had worked on stories with data, they had never encountered such a large volume of information that combined several data sources at the same time.

The FUNES algorithm also included testing processes that were carried out simultaneously against the data that Ojo Público structured and organized to upload to the platform.

Validating the results produced by the tool was a critical part of developing the algorithm. At this point, the weighting given to the various indicators was adjusted to reflect the Latin American context more accurately. For example, Cabral said that the weight of the “campaign contributions” variable was increased. They also had to make adjustments to how the algorithm weighted regional contracts: “FUNES originally gave greater emphasis to local governments due to the number of contracts, but later we saw that a ministry had three contracts that, combined, represented much more money than the contracts in those places.”

Since the Open Contracting Partnership (OCP) also developed a red flag system to detect risks and inefficiencies in contracting, Ojo Público used its model to re-validate the algorithm analysis. “We always ran the same data against the OCP model; if we got the same results, it was a sign that we were on the right track,” Cabral said. The Open Contracting Partnership alert scheme evaluates, among other elements:

- Short bidding periods

- A low number of bidders

- A low percentage of contracts awarded competitively

- A high percentage of contracts with amendments

- Large differences between the value of the award and the final amount of the contract.

Confronting Pre-existing Beliefs

FUNES also had a big impact on the journalists who worked on its development: “The results that the algorithm produced confronted you with your pre-existing assumptions… we were faced with our own prejudices,” Cabral said. “You might have thought the biggest risk of corruption occurred in a certain entity, but the analysis threw something else out. At that time [when developing the tool], we had to verify whether it was our prejudice or indeed if we should adjust the weighting of the indicators.”

The team said that the duration of the project was also a challenge: “It was a full-time job for a year, and we had to keep up the pace, drive, and motivation of the team throughout,” one participant noted.

Automation and New Stories

“There are still many stories to tell,” said Cabral about the use of FUNES. “Our plan is also to automate the process for loading the data onto the platform.” The COVID-19 crisis affected the way newsrooms work all around the world, but it also showed the importance of media investigations into public contracts.

For Cabral, the current crisis is a turning point: “With the pandemic it became clearer that procurement is not something abstract; it affects people. For example, if there is corruption in a contract to purchase masks, within days many people can die. The pandemic highlighted the direct relationship between contracting and violations of human rights, especially those of the most vulnerable.”

FUNES is now an essential part of the investigations carried out by Ojo Público within the framework of the RED PALTA network, an alliance of Latin American media outlets scrutinizing public procurement.

What was the main lesson from FUNES? “We journalists are used to working on specific contracts,” Cabral said. “When we do that, the only thing that happens [as a result of a story] is that they remove the corrupt official, and thus, the corrupt system continues to operate. So we need to say: ‘Let’s not look at one case; let’s not look at ten; let’s put the focus on 200,000 and find the common pattern in all of them.’ That’s what FUNES does. It allows us to have a holistic view of the system, to fight corruption in public procurement more effectively.”

This blog post was originally published on the website of the Open Contracting Partnership and is republished here with permission. It has been lightly edited. Ojo Público is a member of GIJN.

Additional Reading

Researching Government Contracts for COVID-19 Spending

Citizen Investigations: Digging Into Government Records

Document of the Day: Algorithms for Journalists

Romina Colman is a journalist based in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She works on the data team at La Nación, a national daily newspaper, and was previously a Chevening fellow. She also lectures on data journalism at the Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina.

Romina Colman is a journalist based in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She works on the data team at La Nación, a national daily newspaper, and was previously a Chevening fellow. She also lectures on data journalism at the Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina.