The Real Reason I Took a Break From Reporting Aboriginal Deaths in Australia

A collection of articles and photos related to Mark Haines, a 17-year-old Aboriginal Australian, whose death reporter Allan Clarke investigated for six years. Photo: Greg Nelson / ABC

I’m a Muruwari man from far western New South Wales, Australia.

We’re strong stock. Muruwari literally means to fall with a fighting club in your hand. That’s what it feels like I’ve been doing all my life, and as a journalist — fighting unfair battles that no one wants me to win.

I’ve spent most of my career reporting on Indigenous issues. Most of those stories have been about the way Aboriginal people are treated in the Australian judicial system. Aboriginal people make up just over 3% of the Australian population, yet are disproportionately represented in the prison and juvenile justice system.

However, last year, while I was at the top of my career — after winning one of Australia’s most prestigious journalism awards — I stepped away from reporting. I didn’t feel right. Looking back on it now, it was a breakdown. To be honest, I just couldn’t keep reporting on all the injustice leveled at my community, and that’s because I am also part of that community, and these things are happening to my family.

The final blow came at the end of six years of reporting on the unsolved murder of Gomeroi teenager Mark Haines.

In 1988, the 17-year old was found dead on the train tracks in a small city in New South Wales. Despite overwhelming evidence that Mark had been placed there by someone else, the police conducted a perfunctory investigation and concluded that he killed himself — just another drunk Aboriginal boy doing something stupid.

The exhaustion of trying to get some justice for Mark’s family and trying to convince the public — as well as the police — that his life mattered, ate away at me to the bone until I had nothing left to give. The sheer scale of injustice in the case was and remains breathtaking. The depths of despair and grief in that family was and is bottomless.

Snapshot of 17-year-old Mark Haines, whose body was found on the train tracks in New South Wales in 1988. Photo: Courtesy of the Haines family

The reality was that Mark was a Black teenager who no one cared about outside of his family and community. Mark’s story was just one of many; death, after death, after death. I’d report them and then return home to see my own family experiencing the same injustices, day after day after day. Nothing changed. I was becoming numb to the way Australia discards our people like we’re roadkill. Every night I was haunted by the ghosts of my people whose lives were snatched away from them, the sobs of their families echoing in my ears.

In May, I was sitting on my couch in France when I opened Facebook and I saw the video of George Floyd; it was death in real time. It was triggering.

Immediately I was reminded of the video of 26-year-old David Dungay, a Dunghutti man, who died in Sydney’s Long Bay prison in 2015.

David’s crime that day? He’d refused to stop eating from a packet of chocolate biscuits.

Australians should be forced to watch the CCTV footage. It’s brutal. David is pinned under six police officers. He’s face-down, yelling “I can’t breathe.” One officer responds with: “If you can talk, you can breathe.” He’s coughing up blood, and moments later the last bit of air is crushed from his lungs.

Australians should also be forced to watch the CCTV footage of 26-year-old Ms Dhu, (whose first name cannot be revealed due to cultural reasons within her Aboriginal clan, which does not allow first names to be said publicly after death) dying alone in a Western Australian concrete cell. They should be forced to watch as her limp body is dumped in the back of a prison van like a freshly hunted kangaroo.

Her crime? $3,622 of unpaid fines.

Australians should be forced to read Palm Island man Mulrunji Doomadgee’s autopsy report and imagine what it must be like to have one’s liver almost cleaved in two in police custody.

His crime? Walking past a police officer in Queensland, singing “Who let the dogs out.”

I could fill a library with examples. There’s Mr Ward, who was literally roasted alive in the back of a police wagon. There’s David Gundy, who was killed with a shotgun blast to the chest after police raided the wrong home. There’s Tanya Day, who fell asleep on a train and died in custody 17 days later.

It goes on. And on. And on.

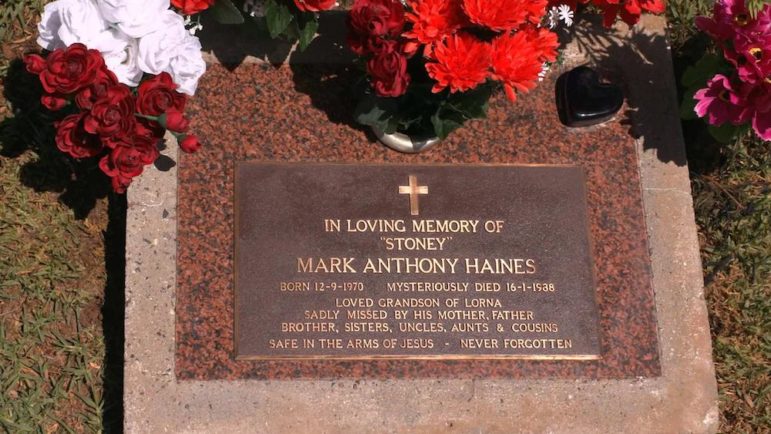

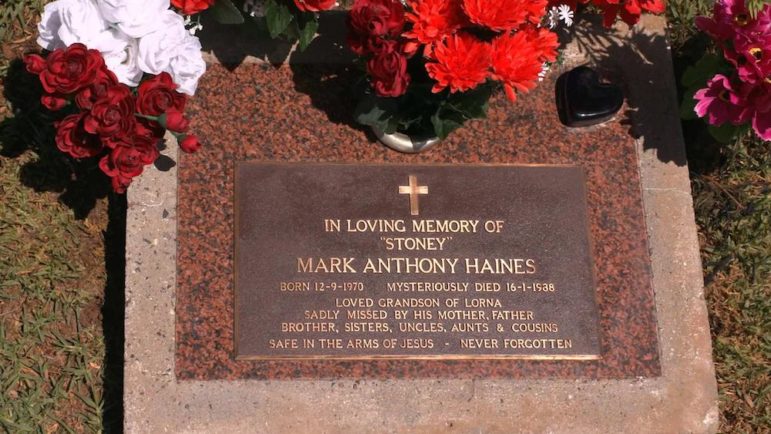

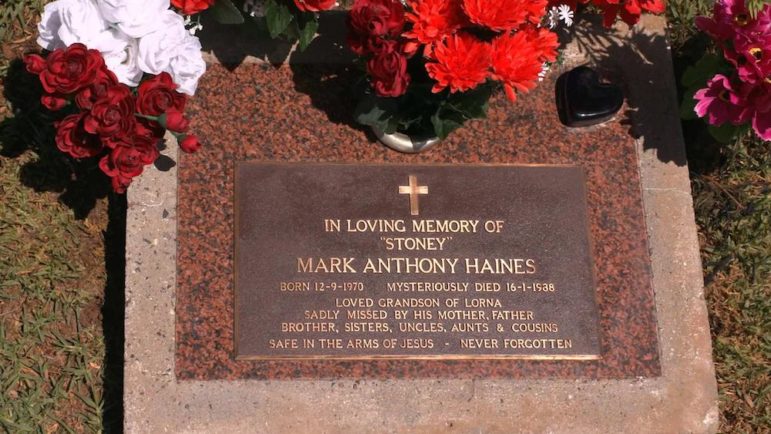

Mark Haines’s gravestone in a cemetery Tamworth, northwestern New South Wales. Photo: Greg Nelson/ABC

The reality is Australians won’t be forced to bear witness to the trauma and the unjust killing of my people. They won’t be asked to put themselves in our shoes because we have always been the other, the fringe dweller.

Is falling asleep on a train a death sentence? Is singing a pop song a death sentence? Even if it’s cheeky? Is having a few thousand dollars worth of fines a death sentence? The answer is ‘yes’, if you’re Black in Australia. Since 1991, there have been at least 432 Aboriginal deaths in custody and it continues to climb. Not one police officer has ever been convicted of murder or manslaughter. Let that sink in.

That’s because Australia, like all countries built on the violence of colonialism and the dispossession of Indigenous people, has created a narrative that says Indigenous people are more likely to be perpetrators of crime, not victims of it.

Now let me go one step further. You think it’s just the judicial system that discriminates? Wrong. Our media are also complicit. They pander to that mentality that I am lesser, that my people are somehow lesser. We are rarely people to them, we’re talent — people to exploit in order for you to receive awards and get a bit of kudos from “woke” colleagues for stepping off the ledge and dipping their toes into the raging pool of racial turmoil. But, in the end, they go home. My people pay the price. Our pain and suffering is often their career gain.

Rarely are deaths in custody presented in context, rarely is our culture presented in context, rarely is our history presented in context. For Aboriginal journalists like me, when we begin our career, we’re expected to take a saw and hack parts of our soul and our lived experiences until they fall away, just to get a bloodied foot in the door.

This reminds me of the first story I ever got published. I was 18 and commissioned by a big mainstream newspaper to write about an event called Reconciliation 2000.

It was a huge day — around 250,000 Australians united to walk across the Sydney Harbor Bridge in solidarity with the Aboriginal community. The day before there was an event at the Sydney Opera House. It was a big deal. The mood outside was almost festive; everyone felt good for doing their bit to try and end racism. In the midst of all this were two older Aboriginal women. They sat directly in front of an official procession on the opera house steps, and held each other, and they sobbed. The procession swept up the stairs and around them as if they didn’t exist.

No one one wanted to be confronted with their trauma. Everyone just wanted to feel good about their solidarity. But I knew those women were part of the Stolen Generations, Aboriginal people who were forcibly removed from their families and placed in government run institutions. They suffered horrific sexual abuse under state care and they had come to tell us about it. I fought to have their story published, but the other media who were there looked the other way. To most Australians, they remained invisible, just like our history.

So, you’re surprised when the day comes where Indigenous journalists speak up and speak out with an authentic voice in the hope of educating the public to the real history of their country, and we’re tagged “activist,” and we’re stripped of our professional credibility; left standing naked? You’re surprised when we’re left exposed to the barrage of hate flung at us on every medium, all the time?

Now Indigenous journalists and journalists of color have started to speak out.

From the desks of some of the world’s largest media organizations, they have bravely shared their personal stories, and it feels like the start of a reckoning that’s long overdue in the fourth estate. Now is not the time for platitudes and piecemeal diversity initiatives from our industry. Now is the time for real substantive introspection and action.

Truth-telling is ugly, but it’s essential.

Everyday Injustices

Back on my couch in France and Facebook, I scrolled through the comments on the George Floyd video, bracing myself for what would inevitably come next. And, just as predictable as the injustices we suffer every day, there it was:

“I’m white and I work hard and I’m better than dirty fucking black people. And if I had the opportunity I’d step on a coon’s neck and kill them too”.

Some things just never change. We can do better, and we must do better. I tried, but, for now, I’m taking a break.

A version of this article first appeared on the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s website and is reproduced here with permission from the author.

More Reading

The Guide for Indigenous Investigative Journalists was created to encourage Indigenous investigative journalists and to provide empowering tips and tools. Developed collaboratively by the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN) and the Native American Journalists Association (NAJA), the guide explores eight key topics, including investigating disappearances.

Allan Clarke is a multi-award winning investigative journalist, writer and producer from Australia. Working across broadcast, radio, podcast and digital, his reporting focuses on the intersection between the Indigenous community and the judicial system. Allan is a descendant of the Gomeroi and Muruwari tribes of far western New South Wales. He helped lead GIJN’s track for Indigenous journalists at the 2019 Global Investigative Journalism Conference.

Allan Clarke is a multi-award winning investigative journalist, writer and producer from Australia. Working across broadcast, radio, podcast and digital, his reporting focuses on the intersection between the Indigenous community and the judicial system. Allan is a descendant of the Gomeroi and Muruwari tribes of far western New South Wales. He helped lead GIJN’s track for Indigenous journalists at the 2019 Global Investigative Journalism Conference.