Photo: Raphael Huenerfauth / huenerfauth.ch

Tips on Investigating Disinformation Networks from BuzzFeed’s Craig Silverman

Craig Silverman talking disinformation at #GIJC19. Photo: Raphael Huenerfauth

Digital disinformation from scammers and political operatives is proliferating around the world, requiring journalists to adapt and respond.

Governments have significantly stepped up social manipulation campaigns in recent years, according to the latest Oxford University research. Another recent research report estimated that disinformation sources make some $200 million in ad revenues each year.

So journalists are increasingly required to investigate strange-looking websites, social media accounts, and patterns of behavior — as well as understand when they are being manipulated.

One of the most fundamental parts of investigating disinformation is looking for the network around a social media account or website, says Craig Silverman, media editor at BuzzFeed News. “Start with one piece of content or site, and pivot on it to identify a larger network through consistent behavior and other connections,” he told the 11th Global Investigative Journalism Conference.

Here is some of Silverman’s top advice to journalists investigating disinformation.

Start at the Beginning

Look at the very first photo a social media account posted, such as a profile picture, and see if that photo received any likes. When people first set up a page, they’ll sometimes like it from their personal account, or their friends and family will. If the account has hidden their list of friends, for example, their relatives might have public lists that will provide further clues.

Facebook pages also have a “page transparency” feature, which allows you to see when the page was created, the location of its managers, whether the page has changed its name, and if it has run any Facebook ads.

Understand Their Network

“It’s not just who they claim to be but who they are interacting with,” Silverman said. Look through their friends, followers, conversations, retweets, shares, and likes, and look for patterns, or things that have changed dramatically over time.

Twitter also has a useful feature on profile pages that automatically recommends other accounts for you to follow. They are likely to be other accounts that interact with each other.

Look Across Platforms

“If there is an information operation going on it is usually cross-platform, using a variety of accounts of entities like websites, pages,” Silverman said. “You need to find what connects all of these things together.”

You can use tools that were originally created for marketers, like Namech_k to see if the same username is used on different platforms. If you find a match, you’ll still need to scrutinize the account to check if there is actually a connection.

Analyze the Content and Engagement

The Facebook-owned social monitoring site CrowdTangle has a browser extension which enables you to track how much web pages are being shared and who by. You can also use another tool, BuzzSumo, to analyze which of a website’s pages have the highest engagement.

This adds important context about the spread and impact of disinformation. Silverman used BuzzSumo, for example, to report on the pro-Trump websites run by Macedonian teenagers in November 2016. The Macedonian websites had already received some coverage, but not this level of detail.

“We were able to say that they were getting insane engagement on Facebook for stories that are completely false,” Silverman said. “It made us have a stronger story because we looked at engagement.”

Look for Connections

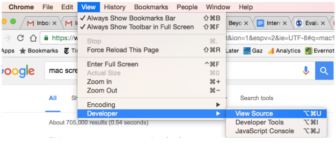

If you’re looking for connections between different websites, one option is to analyze their Google Analytics and AdSense IDs. You need to view the page’s source code and search in the HTML for “UA-” or “Pub-”; these numbers show their IDs, which you can then run through AnalyzeID.com, DNSlytics.com, and spyoneweb.com to find any other sites that share the same ID.

Silverman’s bonus tip: If you can’t find the Google Analytics and AdSense IDs, you can check if this appears in earlier versions of the site by using the Internet Archive’s WayBack Machine. However, he warned to bear in mind that sites do change owners.

Don’t Rush to Attribute to State Actors

“Everyone wants to point the finger at a state to get a scoop but it can be really difficult to meet the standard for attribution,” Silverman cautioned, noting that a lot of disinformation produced for political and financial reasons looks quite similar. “It can be really difficult from digital signals alone to say ‘this is a state operation,’ so be really cautious about that.”

He noted that even the technology platforms sometimes make mistakes about attribution, and they have access to far more data behind such operations. “Attribution is difficult,” Silverman said. “If we do it and get it wrong, that undercuts all of the work that came before that.”

Discuss the Tipping Point

When and how to report on disinformation is often complicated by the consideration that coverage can do more harm than good. It’s useful to consider the “tipping point,” based on the work of Claire Wardle, executive director of First Draft, the nonprofit research, training, and collaborative journalism organization. She defines this as when the story becomes relevant to people outside the niche community in which it originally occurred.

Many information campaigns start in private, anonymous, or niche parts of the web, and journalists can help spread them further by reporting on them. In fact, media coverage may be their main goal.

“If they can get us to pick up their information operation, to spread it unwittingly, that is a huge win for them,” said Silverman. “In some cases, they’re quite happy for us to debunk their campaign because it’s still a win, because it’s still an element of amplification.”

More Resources for Reporting on Disinformation:

Claire Wardle, First Draft: 5 Lessons for Reporting in an Age of Disinformation

Whitney Philips, Data & Society: The Oxygen of Amplification

Joan Donovan and Brian Friedberg, Data & Society: Source Hacking: Media Manipulation in Practice

Danah Boyd, Data & Society: Media Manipulation, Strategic Amplification, and Responsible Journalism

Dart Center: Dealing with Hate Campaigns: Toolkit for Journalists

Charlotte Alfred is an investigative journalist and editor who has reported from the Middle East, Africa, Europe, and the US. Her work has been featured by HuffPost, De Correspondent, The Guardian, News Deeply, Zeit Online, El Diario, and First Draft, amongst others.