Photo: Pexels

Get Crafty: 7 Story Structures to Try Out in Your Next Investigation

العربية | বাংলা | 中文 | Русский

There are many ways to tell a story, and many stories to tell. An investigation can be trying to establish the cause of a problem, or solutions to that problem; it can be revealing previously hidden unethical behavior, or shining a light on issues which are “hidden in plain sight”; it can be holding a mirror up to a part of society to reveal its scale; or giving a voice to that part of society as a step towards a more sophisticated understanding of problems affecting it. And depending on the type of story, you might adopt different approaches to telling it.

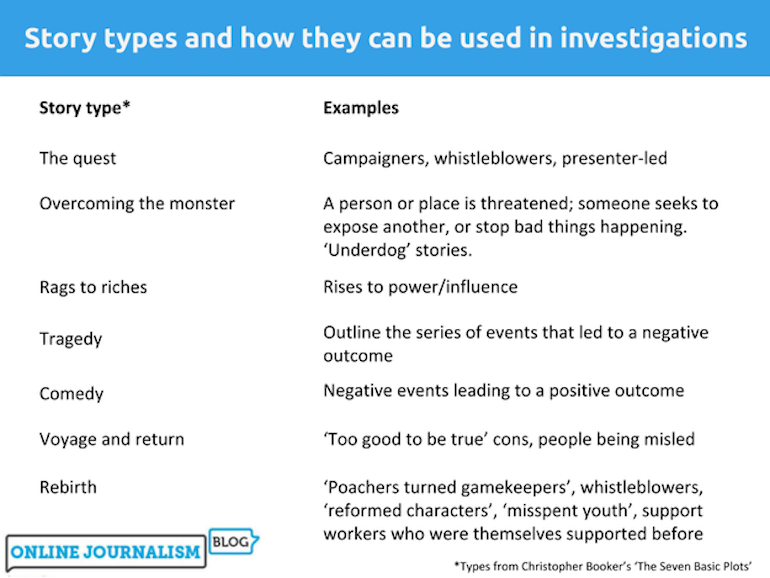

Christopher Booker’s “The Seven Basic Plots” provides a useful set of frameworks. It’s a book about fictional storytelling, but you will find the same structures recurring in long-form and investigative work.

The Quest

A quest narrative (where the protagonist sets off in search of some sort of “prize”) is one of the most common investigative formats, particularly in broadcast where the presenter’s own “quest for the truth” provides a convenient narrative device.

But quests don’t have to be presenter-driven: The story of a campaigner’s quest, for example, or someone inside the establishment who is trying to effect change, a whistleblower or pretty much anyone trying to achieve or uncover something (the “prize” in Booker’s terms) can lead to this sort of approach.

The mystery plot is also mentioned in the book but not listed among the seven. This is essentially a quest to uncover the truth of something, but is worth identifying separately as Booker does.

This form can be the story of your quest to get to the bottom of the truth (useful if you don’t succeed but the journey is still informative). It is a useful back-up option if you anticipate you may not get a satisfactory resolution to your investigation but the information that you have uncovered – and the obstacles you faced – are still important.

Overcoming the Monster

Overcoming the monster is a similar plot, but this specifically involves an antagonist. It may be a faceless one such as a police force, or it may be more concrete such as people traffickers, or a particular individual such as a powerful person suspected of child abuse.

The monster could be threatening a person, a place (a country might be threatened in an investigation into wealth extraction or tax evasion; a town might be threatened in a story about organized crime or environmental change), or even the world (some stories about environmental change or nuclear weapons involve a global threat).

The lawyer who takes the cases no one wants is one example, as the main subject of the story takes on the system to try to represent his clients.

Rebellion Against ‘The One’ (also not included in the seven) is perhaps a darker, dystopian version of this:

“The hero spends the first half of the storyline insistent that he is right, and the power is wrong, but over the course of the story he comes to realize he has a very limited perception of reality, and that the reverse is true. In the end, the hero recognizes the governing force’s right to rule.”

What stories might this suit? Perhaps someone who has switched sides or left behind a rebellious past? Its potential for propaganda leaves this option perhaps less useful than others.

Rags to Riches

Rags to riches plots are self-explanatory. They might be used to tell the story of a person’s rise to power, for example. This is most likely to be a subplot in an investigation but in specialist reporting there are many profiles or interviews with senior figures which fall into this category.

Tragedy

Tragedy is the opposite of rags to riches: It tells the story of a fall from grace, typically because of a specific mistake (it may be that trying to cover up that mistake is what initiates events).

Investigations that revolve around the question “how did this happen” often use this plot: For example after the Grenfell Tower fire or the collapse of Carillion, journalists will dig into the background to see what mistakes led to this – and here you will literally hear the word used: “tragedy.”

The long-form piece “How Boots Went Rogue” is a more subtle example of a tragedy, drawing attention to how a company has strayed from the ideals of its founders and employees.

Voyage and Return

Voyage and return follows a journey “there and back.” The key point here is that there must be a reason for the person to have to come back: It may be because something turns out to be too good to be true.

Examples in investigations include trafficking (a person is tempted by misleading claims of conditions, and must then make their way back home); whistleblowing (someone gets a great job but discovers things aren’t as they should be – see the film “Snowden” for one example of this); or even perhaps change-of-career stories (the footballer who has a career-ending injury and has to return home to start again).

The investigation “Follow the Money,” which I produced with Yemisi Akinbobola and Ogechi Ekeanyawu, uses this approach as it follows aspiring footballers from Nigeria as they are transported to Cameroon and abandoned. Once we had the facts of those events we knew it would probably be an important part of the eventual narrative.

Rebirth

Rebirth plots have a similar focus on a “return” – in this case it is a return from some form of death, i.e., a rebirth. “Redemption” may in some cases be a better term.

Snow White is perhaps the best-known example (she is trapped in a 100-year sleep before being woken by a prince) but “The Frog Prince” or “Beauty and the Beast” are perhaps better examples: In each case the protagonist is trapped in some form (frog/beast) and redeem themselves in some way to escape it (be “reborn”).

“A Christmas Carol” is perhaps more useful for journalistic purposes: This is the story of a mean business owner who is reborn as a generous benefactor, and how that transformation happens is the subject of the story.

Again, this might be useful for profiles and interviews. Investigations regarding “poachers turned gamekeepers” (or whistleblowers) might also fit this plot.

“The Uncatchable” is one example from journalism: It tells the story “of how Greece’s most wanted man became a folk hero.”

Comedy

Comedy plots are less common in journalism, probably because they do not tend to deal in serious subjects, and/or may be seen to trivialize those. These plots are not comedies in the sense that they are humorous, but in the sense that “things go wrong” and are then righted.

Shakespeare’s comedies are the best-known examples of these: stories full of misunderstandings, with a wedding at the end. If you hear a story of a “comedy of errors” (the phrase itself comes from an early Shakespeare play) then that’s a clue that the comedy plot might work – but be careful it doesn’t end up twee.

Perhaps the best recent example I’ve seen of a comedy plot is the Twitter thread above. I do hope it’s true…

Combining Plots

Bear in mind that one story might have multiple plots. A campaigner might be on a quest, but that might involve overcoming one or more monsters along the way. Scrooge’s story of rebirth also involves a rags to riches tale and the accompanying tragedy of his broken engagement to Belle, both of which are told as part of the Ghost of Christmas Past section.

Try to be clear which is the bigger story, and which are smaller elements of that (subplots).

Questioning the Plot

Of course these plot forms are only devices to help you understand the information that you have collected, and the sorts of stories that they might be telling. It does not mean that we seek to force the facts into an unsuitable box, or to misrepresent events.

The fact that a story fits into the “rags to riches” form, for example, does not alter that story; it only helps us to better communicate it to editors, and think more clearly about what that means both in terms of the structure of the telling, and the issues it raises.

For example, you might draw attention to the fact that it is “no ordinary rags to riches story” or “her journey was not a straightforward one”; you might critically interrogate whether the rags to riches story is all that it seems (the tweet below is a great example of drawing attention to the way that the myth of the entrepreneur can be better interrogated).

This critical stage is important. Humans naturally create patterns from noise (including random noise), and journalists are professional pattern-makers: Events are structured into sequences that can be understood, stripped back to the essentials.

We do this anyway, so making it explicit by thinking about story forms can help us push further and test whether we are reaching for those forms unthinkingly.

Some questions to ask, then, once you realize the sort of story you are leaning towards, include:

• Is the “monster” really a monster — why has it ended up that way? (Perhaps it is on a quest too?)

• Is a quest inherently good? (Answer: No.) What unintended consequences does it have?

• In a “voyage and return,” do you have all the facts about why someone returned?

• Is someone hiding information in order to make a story look like “rags to riches”?

• Have they really been “reborn”?

• Losers are rightly the focus in a tragedy — but are you failing to look for those benefiting from a tragedy?

Ultimately this is one of the biggest values of the story form: By externalizing the narrative we inevitably lean towards (and those we speak to), it helps us avoid blind spots.

This article first appeared on Paul Bradshaw’s Online Journalism Blog and is reproduced here with permission.

Paul Bradshaw runs the MA in Data Journalism and the MA in Multiplatform and Mobile Journalism at Birmingham City University and is the author of a number of books and book chapters about online journalism and the internet, including the “Online Journalism Handbook,” “Finding Stories in Spreadsheets,” “Data Journalism Heist,” and “Scraping for Journalists.”

Paul Bradshaw runs the MA in Data Journalism and the MA in Multiplatform and Mobile Journalism at Birmingham City University and is the author of a number of books and book chapters about online journalism and the internet, including the “Online Journalism Handbook,” “Finding Stories in Spreadsheets,” “Data Journalism Heist,” and “Scraping for Journalists.”