You Won’t Kill the Message: How Investigative Journalists Are Pushing Back Against Attacks

Matthew and I talk about sail boats. Pavla and I talk about beer.

Matthew and I talk about sail boats. Pavla and I talk about beer.

Like me and 600 others, these two ordinary-seeming colleagues had come to Norway for a weekend in April to attend a conference on investigative reporting.

Yet ordinary they are not.

Matthew’s mother, Daphne Caruana Galizia, was a Maltese investigative journalist silenced by a car bomb last October. For years she had exposed political corruption and dirty money flows in the tiny European Union country.

Pavla Holcová, a Czech, worked closely with Slovak journalist Ján Kuciak, who was assassinated in his home last February, with two bullets through his chest. In all likelihood, this was the result of their collective research into the close connections between the Italian Mafia and the higher echelons of Slovakia’s political system.

Investigative journalism is characterized by systematic effort and perseverance. It holds power to account. It can hit hard. And this makes it dangerous. Not just for those at the center of the stories but also for the people who write the stories, and for people close to them.

Pavla is living under Czech police protection. Security experts have warned Matthew against returning to Malta.

Exposing Powerful Interests

Infographic from Reporters Without Borders

Worldwide, a total of 65 journalists were killed in 2017, according to the organization Reporters Without Borders.

Of these, 39 were murdered or directly targeted because their work threatened political, financial or criminal interests, states the organization’s annual report.

While it is well known that journalists are at risk in countries such as Mexico, Turkey and Russia, it is very uncommon for the work of journalists within the EU to cost them their lives.

What Ján and Daphne, the two journalists who were killed, shared was the classic journalistic approach of “following the money.”

One of the most skilled investigative reporters in Putin’s Russia right now, Roman Anin from the opposition paper Novaya Gazeta, expressed it succinctly in a conversation last year: Banking statements are his “favorite documents” because they show where the money comes from and who receives it.

At Danish daily Berlingske, for our series on money laundering at Denmark’s biggest bank, Danske Bank, we pored over more than 100,000 of the bank transactions that Anin loves. These revealed, among other things, that the Azerbaijani regime systematically sent large sums of money through the Estonian branch of Danske Bank to recipients, including senior European politicians, and that both the Putin family and Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) apparently also laundered their dirty money through the bank. All of this happened because Danske Bank did not put a stop to it.

We collaborated with the the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) and journalists across 15 countries – because money from organized crime and corrupt politicians does not stop at any national border. It winds its way through secret accounts under fake names in offshore tax shelters, from one bank to another, from one country to another.

This is why investigative journalists also need to work together across borders.

Finish Their Work

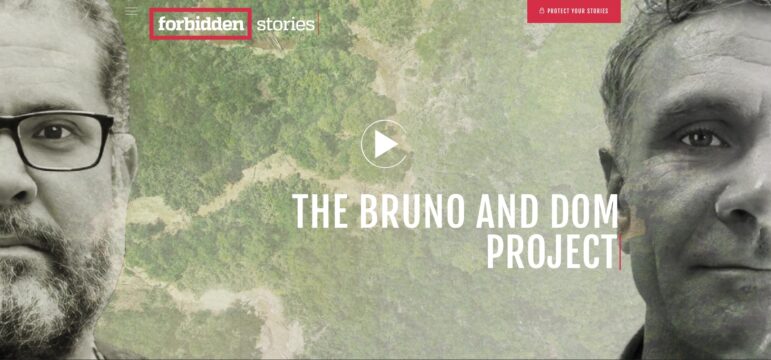

This is exactly the message coming from 45 journalists in 15 countries who have been collaborating for the past six months to continue the work of Daphne Caruana Galizia, together with the NGO Forbidden Stories.

Looking for Completion: Journalists from 15 countries collaborated with Forbidden Stories on the Daphne Project to continue the work of Daphne Caruana Galizia before she was murdered. Image: Screenshot

French documentary journalist Laurent Richard, who founded the NGO, sees collaboration as “the best protection.”

”What is the point of killing a journalist if 10, 20 or 30 others are waiting to carry on their work?” said Richard. “Whether you’re a dictator, the leader of a drug cartel or a corrupt businessman, exposure of your crimes is your biggest fear. Journalists are the enemy of the corrupt ecosystem that you have constructed.”

The Forbidden Stories platform allows journalists to upload any material they are working on if they fear for their lives or fear being jailed.

The message of Laurent Richards is clear:

“You killed the messenger. But you won’t kill the message.”

The Daphne project “feels like a taste of justice,” said her son, Matthew.

He hopes that one day he will be able to return to Malta and buy himself a boat.

This comment was originally published in Berlingske and b.dk.

Eva Jung is an investigative journalist and Brussels correspondent for Danish daily Berlingske. She is on the board of the Global Investigative Journalism Network, on the advisory board of Dataharvest and former deputy chair of the Danish Association for Investigative Journalism.

Eva Jung is an investigative journalist and Brussels correspondent for Danish daily Berlingske. She is on the board of the Global Investigative Journalism Network, on the advisory board of Dataharvest and former deputy chair of the Danish Association for Investigative Journalism.