The website of "Maisy Kinsley," who does not actually exist.

With the Proliferation of Fake Profiles, Old School Vetting Signals Don’t Work

The website of “Maisy Kinsley,” who does not actually exist.

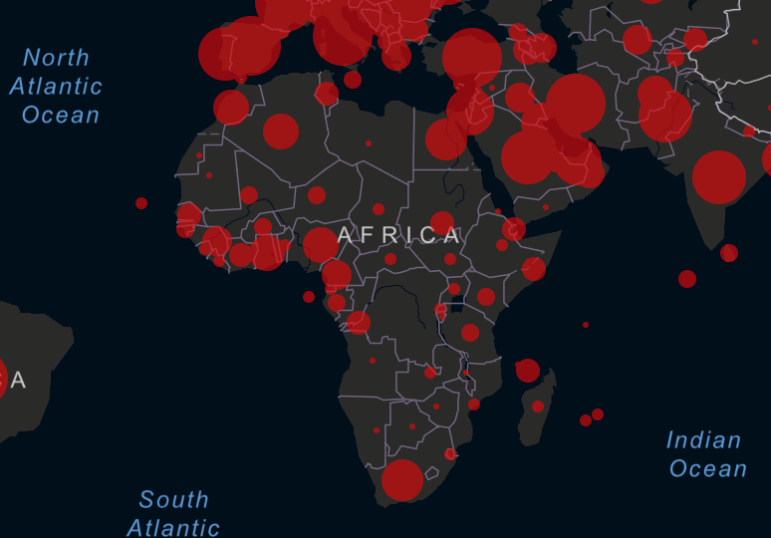

There was a story going around recently about a “reporter” who was following people shorting Tesla stock and allegedly approaching them for information. I won’t go into the whole Elon vs. the Short Sellers history; you don’t need it. Let’s just say that posing as a reporter can be used for ill in a variety of ways and maybe this was a case of that.

Snapshot of Maisy Kinsley’s profile.

The way a lot of people judge reputation is signals, the information a person chooses to project about themselves. Signals can be honest or dishonest, but if a person is new to you, you may not be able to assess the honesty of the signal. What you can do, however, is assess the costliness of the signal. In the case of a faker, certain things take relatively little time and effort, but others take quite a lot.

Let’s list the signals, and then we’ll talk about their worth.

First there’s the Twitter bio and the headshot. The headshot is an original photo — a reverse image search here doesn’t turn up Maisy, but it doesn’t turn up anyone else — so it’s less likely to be a stolen photo. The Twitter bio says she’s written for Bloomberg.

This isn’t that impressive as verification, but wait! Maisy also has a website, and it looks professionally done!

Maisy’s website.

From the website we learn that she’s a freelancer. Again, user supplied, but she links to her LinkedIn page. She’s got 194 connections, and is only 3 degrees of separation from me! (I’m getting a bit sick of this photo, but still.)

LinkedIn profile.

Oh, and she went to Stanford! Talk about costly, right? You don’t do that on a whim!

Screenshot of education panel in LinkedIn.

The Usual Signals Are Increasingly Garbage

Here’s the thing about all the signals here: They are increasingly garbage, because the web drives down the cost of these sorts of things. And as signals become less costly, they are less useful.

Your blurb on Twitter is produced directly by you — it’s not a description on a company website or in a professionals directory. So, essentially worthless.

That photo that’s unique? In this case, it was generated by machine learning, which can now generate unique pictures of people that never existed. It’s a process you can replicate in a few seconds at this site here, as I did to generate a fake representative and fake tweet below.

The website? Domains are cheap, about $12 a year. Website space is even cheaper. The layout? Good layout used to be a half-decent signal that you’d spent money on a designer — 15 years ago. Nowadays, templates like this are available for free.

LinkedIn, though, right? All those connections? The education? I mean, Stanford, right?

First, the education field in LinkedIn is no more authoritative than the bio field in Twitter. It’s user supplied, even though it looks official. Hey, look, I just got into Stanford too! My new degree in astrophysics is going to rock.

Screenshot of a fake degree I just gave myself on LinkedIn. I deleted it immediately after; fake-attending Stanford was messing up my work-life balance.

The connections are a bit more interesting. One person called one of Maisy’s endorsements to see if they actually knew this person. Nope, they didn’t. Just doing that thing where you don’t refuse connections or mutual endorsements. “Maisy” just had to request a lot of connections and make enough endorsements and figure that enough of a percentage would follow or endorse her back. Done and done.

I’ll tell you a funny story, completely true. I once friended someone on LinkedIn that I knew, Sara Wickham or somesuch. And we went back and forth talking about our friends in college in 1993 — “Remember Russ?” “Guy with the guitar, always playing the Dead and Camper Van Beethoven?” “Oh you mean Chris?” “Right, Chris.” “Absolutely. Whatever happened to Chris, anyway?”

A week or so into our back and forth I noticed we had never attended the college at the same time, and as I dug into it, I remembered the person I was thinking of didn’t have that last name at all. I had never met this person I was talking with, and in fact we had no common friends.

That’s LinkedIn in a nutshell. Connections are a worthless indicator.

Stop with the “Aha, I Spotted Something” You’re Firing Up in Your Head

So now maybe you’re channeling your inner Columbo and just dying to tell us all about all the things you’ve noticed that “gave this away.” You would not have been fooled, right?

I mean, there’s a five-year work gap between Stanford and reporting. She graduated in 2013 and then started just *now*. Weird, right? There’s a sort of bulge in the photo that’s the tell-tale sign of AI processing! And it’s the same photo everywhere! The bio on the website sucks. The name of her freelancing outfit is Unbiased Freelancing and Storytellers, which feels as made up a name as Honest Auto Service.

Here’s the thing — you’re less smart if you’re doing this stuff than if you’re not. You know the person is fake, and so what you’re doing is noticing all the little inconsistencies.

But the problem is that life is frustratingly inconsistent once put under a microscope. The work gap? People have kids, man. It’s not unusual at all — especially for women — to have a work gap between college and their first job. If that’s your sign of fakery, you’re going to be labeling a lot of good female reporters fake.

That photo? Sometimes photos just have weirdness about them. Here’s the photo of a Joshua Benton on Twitter, who tweets a lot of stuff.

Joshua Benton’s Twitter profile picture.

Joshua’s Twitter bio claims that he’s a person running a journalism project at Harvard, so it’s a bit weird he’s obscuring what he looks like. Definitely fishy!

Except, of course, Benton does work at Harvard, and in fact runs a world-famous lab there.

What about Maisy’s sucky bio? Well, have you ever written a sucky bio and thought, I’ll go back and fix that? I have. (A lot of them made it all the way into conference programs.)

And finally the name of her freelance shop: Unbiased Freelancing and Storytellers. Surely a fake, right?

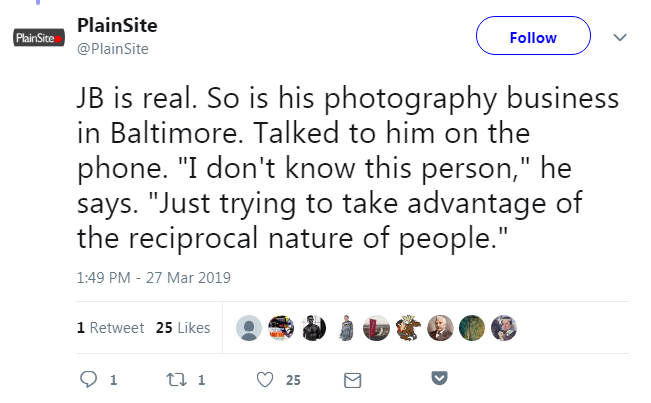

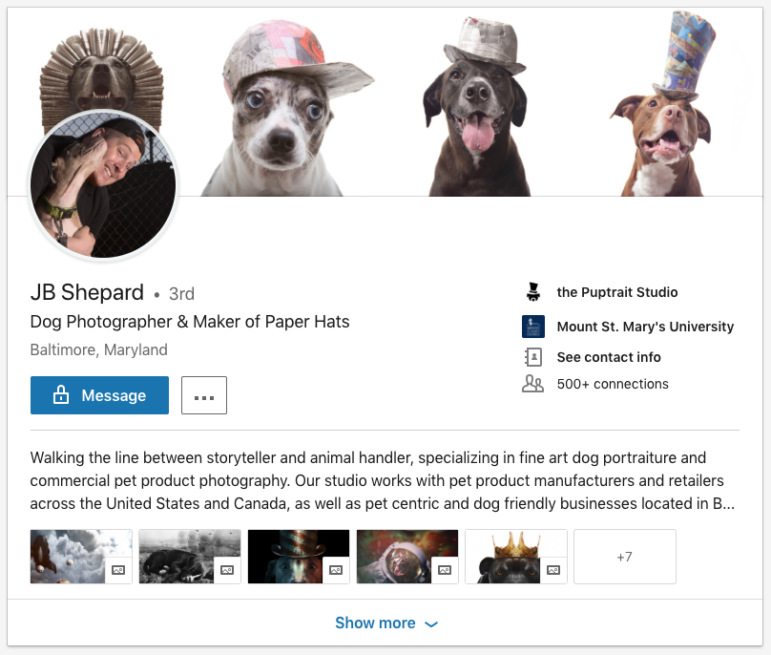

Funny story about that. A bunch of Twitter users were investigating this story and looking at her LinkedIn connections/endorsements. And one of them found the clearly fake Mr. Shepard, a “Dog Photographer and Maker of Paper Hats”:

Do I have to spell this out for you? His name is Shepard and he photographs dogs. Look at the hats, which are CLEARLY photoshopped on (can you see the stitching?). His bio begins “Walking the line between storyteller and animal handler …” Come ON, right?

Except then the same person called the “Puptrait” studio. And JB is real. And his last name is really Shepard.

This puppy is real and is really wearing that hat. They are also super adorable, and if you want a picture like this for your own pet (or just want to browse cuteness for a while in a world that has gotten you down) you should check out Shepard’s Puptrait Studio. Picture used with kind permission of JB Shepard.

And the hats aren’t photoshopped, he really does make these custom paper hats that fit on dogs’ heads.

If you’d think this was fake, don’t blame yourself — when reading weak and cheap signals you are at the mercy of your own biases as to what is real and what is not, what is plausible and what is not. You’ll make assumptions about what a normal work gap looks like based on being a man, or what a normal job looks like based on being something that isn’t a dog photographer and maker of paper hats.

I actually used to do this thing where I would tell faculty or students that a site was fake, and ask them, how do we know? And they would immediately generate *dozens* of *obvious* tells — too many ads, weird layout, odd domain name, no photos of the reporters, clickbait-y headlines, no clear “about” page. And then I would reveal that it was actually a real site. And not only a real site, but a world-renowned medical journal or Australia’s paper of national record.

I had to stop doing this for a couple reasons. First, people got really mad at me. Which, fair point. It was a bit of a dick move.

But the main reason I had to stop is after having talked themselves into it by all these things they noticed, a certain number of the students and faculty could not be talked out of it, even after the reveal. Each thing they had “noticed” had pulled them deeper into the belief that the site was faked and being told that it was actually a well-respected source created a cognitive dissonance that couldn’t be overcome. People would argue with me. That can’t really be a prestigious medical journal — I don’t believe you! You’ve probably got it wrong somehow! Double-check!

It ended up taking up too much class time and I moved on to other ways to teach it. But the experience actually frightened me a bit.

Avoid Cheap Signals. Look For Well-Chosen Signs.

By looking at a lot of poor quality cheap signals, you don’t get a good sense of what a person’s reputation is. Mostly, you just get confused. And the more attributes of a thing you have to weigh against one another in your head, the more confused you’re going to get.

This situation is only going to get worse, of course. Right now AI-generated pictures do have some standard tells, but in a couple years they won’t. Right now you still have to write your own marketing blurb on a website, but in a couple years machine learning will pump out marketing prose pretty reliably, and maybe at a level that looks more “real” than stuff hand-crafted. The signals are not only cheap, they are in a massive deflationary spiral.

What we are trying to do in our digital literacy work is to get teachers to stop teaching this “gather as much information as you can and weigh it in a complex calculus heavily influenced by your own presuppositions” approach and instead use the network properties of the web to apply quick heuristics.

Let’s go back to this “reporter.” She claims to write for Bloomberg.

Snapshot of Maisy Kinsley’s profile.

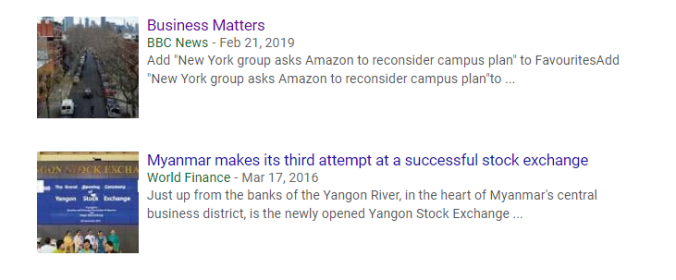

Does she? Has she written anywhere? Here’s my check:

Screenshot of Google News.

I plug “Maisy Kinsley” into Google News. There’s no Maisy Kinsley mentioned at all. Not in a byline, not in a story. You can search Bloomberg.com too and there’s nothing there at all.

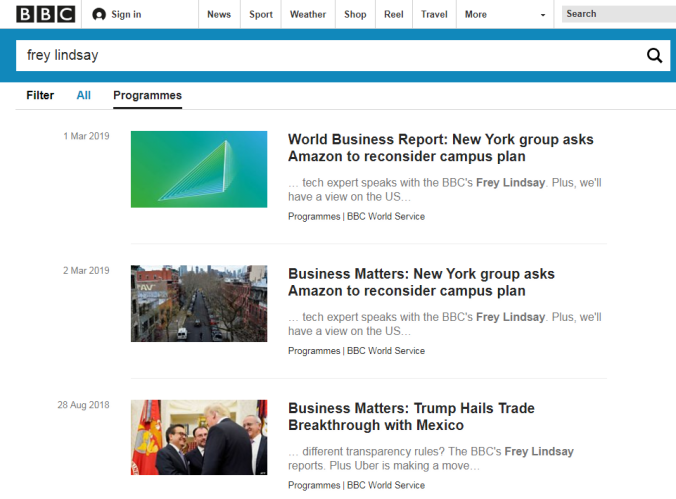

Let’s do the same with a reporter from the BBC who just contacted me. Here’s a Google News search. First a bunch of Forbes stuff:

A search for Frey Lindsay turns up many stories from Forbes in Google News.

Downpage some other stuff including a BBC reference:

If we click through to BBC News and do a search, we find a bunch more stories:

We’re not looking at hair, or photos, or personal websites or LinkedIn pages, or figuring out if a company name is plausible or a work gap explainable. All those are cheap signals that Frey can easily fake (if a bad actor) and we can misread (if he is not). Instead we figure out what traces we should find on the web if Frey really is a journalist. Not what does Frey say about himself, but what does the web say about Frey. The truth is indeed “out there”: it’s on the network, and what students need is to understand how to apply network heuristics to get to it. That involves knowing what is a cheap signal (LinkedIn followers, about pages, photographs), and what is a solid sign that is hard to counterfeit (stories on an authoritative and recognizable controlled domain).

Advancing this digital literacy work is hard because many of the heuristics people rely on in the physical world are at best absent from the digital world and at worst easily counterfeited. And knowing what is trustworthy as a sign on the web and what is not is, unfortunately, uniquely digital knowledge. You need to know how Google News is curated and what inclusion in those results means and doesn’t mean. You need to know followers can be bought, and that blue check marks mean you are who you say you are but not that you tell the truth. You need to know that it is usually harder to forge a long history than it is to forge a large social footprint, and that bad actors can fool you into using search terms that bring their stuff to the top of search results.

We’ve often convinced ourselves in higher education that there is something called “critical thinking,” which is some magical mental ingredient that travels, frictionless, into any domain. There are mental patterns that are generally applicable, true. But so much of what we actually do is read signs, and those signs are domain specific. They need to be taught. Years into this digital literacy adventure, that’s still my radical proposal: that we should teach students how to read the web explicitly, using the affordances of the network.

This article first appeared on Mike Caulfield’s website, Hapgood, and is reproduced here with permission.

Mike Caulfield is the director of blended and networked learning at Washington State University Vancouver, and head of the Digital Polarization Initiative of the American Democracy Project, a multi-school pilot to change the way that online media literacy is taught.

Mike Caulfield is the director of blended and networked learning at Washington State University Vancouver, and head of the Digital Polarization Initiative of the American Democracy Project, a multi-school pilot to change the way that online media literacy is taught.