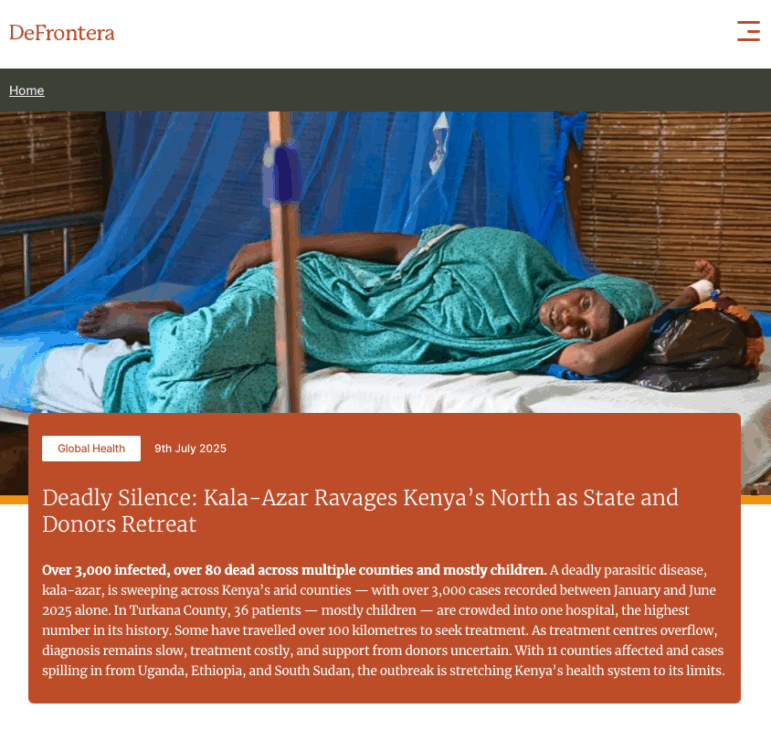

A nurse attends to a patient in Marsabit, Kenya. A recent DeFrontera story explored an outbreak of a deadly disease in that county and 10 others in northern Kenya. Image: Shutterstock

Why Two Kenyan Journalists Launched a Startup to Change Global Health Storytelling

For years, over coffee in Nairobi cafés, Verah Okeyo and Anne Mawathe traded stories of health investigations that took weeks to report, only to be condensed into a few paragraphs, two-minute clips, or dropped entirely.

Both seasoned health journalists, they grew frustrated with newsroom constraints and began to imagine a platform where health reporting could breathe. They envisioned longform, deeply reported stories that communities, policymakers, and global audiences could not ignore.

Out of that frustration came DeFrontera, created to fill a gap in African media with sustained, evidence-driven health journalism.

Already, DeFrontera’s reporting has covered investigations into how a once-model maternal health program in a Kenyan county collapsed under the weight of systemic failures; how simple but transformational protocols in another county dramatically reduced maternal deaths from postpartum bleeding; the alarming resurgence of deadly parasitic disease kala-azar in northern Kenya amid waning donor and government support; and an innovative “one health” initiative that delivers both veterinary and human vaccines to reach nomadic communities.

Guiding this ambitious editorial vision are two leaders with deep roots in both journalism and health. Okeyo, the chief executive and publisher, combines global health reporting with leadership experience at health nonprofit Jhpiego and the Nation Media Group, where she honed her ability to design editorial systems that uphold rigor and nurture emerging health journalists.

Mawathe, the editor-in-chief, brings decades of experience, including senior roles as chief producer of visuals for Africa at Reuters and Africa Health Editor at the BBC. She is recognized for transforming complex health data into engaging stories that have driven policy change and institutional accountability.

Together, the co-founders are positioning DeFrontera as a trusted voice in African health reporting, providing a platform for stories and perspectives often overlooked by mainstream media. I asked them about their vision, the challenges of building an independent outlet, and the role African journalists must play in global health debates. Our conversation has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

Q: How does DeFrontera approach telling health stories differently than legacy newsrooms you’ve worked in in the past?

Verah Okeyo: In legacy media, stories are often chosen for advertising, sales potential, and sometimes prestige. The order is politics, sports, then what I call MERSH: medicine, education, research, science, and health. Politics and sports receive investment, training, and resources. Science, health, and education are treated as something prestigious.

A recent story by DeFrontera examined a surge of cases of the deadly disease visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) in northern Kenya. (Image: Screenshot, DeFrontera

Because of that little investment, the quality of reporting is not going to be there. Too often, health is treated like politics, with shock, yet these are people’s lives, and audiences make decisions based on that reporting. Science coverage requires reading journals and talking to multiple types of people just to triangulate one thing. It is not a “he-said, she-said” kind of situation.

Another gap we were finding is how newsrooms manage content. You can spend a week in the field and end up with a two-minute story. At DeFrontera, we use what we call the circular economy: reusing content until there is nothing left, tailored for different audiences such as policymakers, healthcare workers, and the public. One story might run as a YouTube feature, then be broken into smaller parts for Instagram, LinkedIn, TikTok, WhatsApp, and so on.

Anne Mawathe: Mainstream media tend to report stories because a certain organization has given them data. They have done the research, and the media just report things like, “Kenya ranks among the top 10 countries with the highest mortality rate.” But we are not saying why this should matter. We want to turn these into public impact stories that reach people. We especially want to reach decision-makers with our storytelling.

Q: How do you center communities in your work?

AM: For us, engaging communities is a loop. It does not end when the story is published. We go back to the communities so they can see the story, give feedback, and have discussions. We hold forums with local health leaders. There, the community can share their reactions and pose questions to their local leaders. We want to give communities tools, language, and accessible storytelling so they can claim what belongs to them. We also encourage leaders to grant access.

Q: How do you ensure ethical storytelling in contexts where people are experiencing illness, stigma, or systemic neglect?

Verah Okeyo, DeFrontera publisher and CEO. Image: Pulitzer Center

VO: We have a principle that ours is a do-no-harm kind of journalism because for us, it is paramount that we are respectful in the way we tell our stories. Anne and I are very experienced reporters, so we course-correct as we go, and we also draw from both life and professional experiences to ensure ethical storytelling. For example, at Jhpiego, informed consent was standard. We practice the same: if someone appears in our stories, we explain where the material will go and its impact, then get their consent. We are also intentional about language.

Q: What structural inequities do Global South journalists face when working with international media?

VO: Often, the stories international editors want are inaccurate because they come with a narrow perception of Africa’s health systems. For example, during COVID, Africans were better prepared than assumed because we have long dealt with deadlier zoonotic diseases like Ebola and Rift Valley fever. Our doctors and clinical officers are trained to work in low-resource settings. Yet external editors arrive with “confident ignorance.” They may even try to misframe visuals, such as filming long queues of patients that have nothing to do with the disease in question, just to fit a narrative.

AM: My experience at the BBC and later Reuters showed me that the problem also lies in structural power. Too often, reporting is shaped by parachuting journalists or external fixers. When Africans themselves edit and produce these stories, we reclaim the narrative. At Reuters, as the first African woman in my position, I pushed for Africans to own their stories. But inequities remain: global funding systems, research agendas, and editorial control still sit in the Global North. During COVID, however, we saw that Africa could teach the West how to manage outbreaks. This gives me hope that the dynamic is changing.

Q: What kinds of gatekeeping or skepticism have you personally faced as African journalists reporting on global health, and how do you navigate it?

VO: I’ve experienced gatekeeping on two levels. First, within medicine and global health itself: if you’re not from that background, people assume you’ll get it wrong. Scientists and doctors are cautious, and sometimes won’t speak unless they can review your copy. We refuse this unless it is highly technical and specialist input is necessary. To navigate this, I immerse myself in the field: I read medical journals, attend conferences, and pay for memberships in professional societies, like the Kenya Obstetric and Gynaecological Society and the Nurses Association of Kenya. This helps me understand clinic realities and connect medicine with politics. The second layer is international: external editors often assume Africans are helpless and waiting for saviors. Over time, as they see our expertise and preparation, this gatekeeping lessens.

Q: Have you encountered resistance to your approach from within journalism or from institutions you report on, and how did you respond?

VO: Resistance comes from both journalism and institutions. Within journalism, some dismiss your work as “not new” or “just another startup.” I counter this with my experience and access, which allows me to pursue stories others can’t. From healthcare, resistance occurs because I straddle roles as journalist and medical anthropologist. Physicians may expect me to understand the system fully or refrain from critique, but my focus is on patient needs. Critiquing healthcare practices often meets pushback because doctors are seen as untouchable. NGOs and donors also exert control, sometimes wanting to pre-review stories to avoid upsetting funders. I navigate this by working through counties or local authorities, allowing stories to be published without giving agencies editorial control.

Q: What has it been like to lead a media organization as women in the industry?

VO: So far, our gender has worked in our favor and opened opportunities for two main reasons. First, the respect the industry has given us because of our experience. People expected we would bring different skills. Anne has been in the health and human rights beat for over 20 years in broadcasting. She was BBC Africa’s founding health editor, covering the continent and leading productions where health stories were reported in Swahili, English, and French. She kept that momentum even as Reuters Africa’s head of visual. I have been known for my extensive coverage of medicine and public health, and also for my grant-writing and fundraising work at the Nation. My time working at Jhpiego and pursuing a PhD in medical anthropology also added to that credibility.

There is also a culture that assumes, because we are women, we will report on health better. We have noticed, for instance, that health administrators are more willing to allow us into maternity wards compared to our male colleagues, even when both have official permission.

Q: How are you approaching funding and long-term sustainability, and what challenges have you faced?

VO: For now, funding isn’t an immediate worry. We have seed support from the International Center for Journalism and the Gates Foundation for the next three-and-a-half years. Anne and I have had to learn to think like fundraisers. When we cover a story, we already consider how it can be positioned to attract support while remaining true to our mission. As a nonprofit, advertising is not an option, so partnerships are crucial. Building these relationships takes time, careful communication, and understanding the language of funders. We show researchers the impact of their work through storytelling, without compromising editorial independence. Sustainability also involves operational efficiency and creativity. We reduce costs by sharing tasks across our team and ensure every story is solid, grounded in evidence, and ethically reported. Over time, these small, consistent efforts help build a product and reputation that funders can trust, allowing us to maintain independence while securing support.

Q: What advice would you give to emerging journalists from the Global South who want to cover health stories but face under-resourced or extractive systems?

Anne Mawathe, DeFrontera editor-in-chief. Image: DeFrontera

AM: Stick with the basics. Know why you exist as a journalist and commit to showing up. There is no way to succeed without engaging directly with people. Modern journalism sometimes encourages sitting at your desk, doing social listening, and thinking that is enough. It is not. You must speak to real people, understand their specialities, and extend beyond online observation. You do not have a monopoly on ideas. If someone else covers a story similar to yours, it does not mean they copied you. Put in the work and consistently do your job. The impact of your reporting and the fact that you are producing work with life and meaning should be enough motivation.

VO: Global health journalism also requires an entrepreneurial mindset. Most newsrooms cannot fund health stories due to elitism and limited resources, so you must find ways to sustain your work. First, you need to genuinely care about people and be committed to their well-being.

Second, read widely, particularly in biomedical sciences. Knowledge is essential. Third, you need to be able to sell your ideas. Grant applications and partnerships require persuasion. Study marketing, advertising, and successful campaigns. I observe advertising videos and analyse them for lessons. You need to make your journalism a product that is visible, fast, and compelling.

Finally, speed and timing matter. Your story must reach funders, platforms, and audiences quickly, even before you meet them.

Stick with the basics. Know why you exist as a journalist and commit to showing up. There is no way to succeed without engaging directly with people.

Q. How do you take care of yourselves and manage your mental health?

Mawathe: Going to the gym regularly helps me a lot, and sometimes I unload on Verah, which helps too. Doing post-mortems after an assignment gives me relief. The hardest part is reliving the interviews while editing or producing the story. Over time, you learn to pace yourself. I also watch documentaries, mostly on African history, which shifts my focus from the heaviness of the stories. Giving yourself immediate breaks after intense assignments is crucial, something most journalists in newsrooms cannot do because of the workload. That pause is important for mental health.

Okeyo: I have a strong constitution, and I rarely get shocked. I prepare myself psychologically by mapping out the journey of a story and anticipating challenges. My upbringing helped; my mother was a nurse and midwife, and I grew up assisting her with deliveries and community healthcare. That experience gave me resilience and a calmness in the face of trauma. When stories feel heavy, I use physical activity like the gym or martial arts to release stress. Sleep also helps.

I am also fortunate to have friends and colleagues who are doctors and nurses, so I can gauge the severity of what I witness. They give perspective on cases, which helps me manage anxiety. My personal temperament is naturally phlegmatic, which keeps me steady. Anne and I also balance each other; my calm complements her energy

Editor’s Note: This story was originally published by The Reuters Institute and is republished here with permission.

Maurice Oniang’o is an award-winning freelance multimedia journalist and documentary filmmaker based in Nairobi, Kenya. He has written for National Geographic, 100 Reporters, Africa.com, and Transparency International, among others. A National Geographic Explorer recipient, he has also produced documentaries for National Geographic’s Ultimate Vipers, as well as Project Green, Africa Uncensored, NTV Wild, and Tazama.