Photo: Shutterstock

The Growing Global Reach of Chinese and Russian Information Controls

Photo: Shutterstock

Within the borders of China and Russia, the use of invasive information controls and techniques is well-known and widespread. Surveillance of citizens’ private communications is commonplace, while state-mandated censorship is pervasive. But the use of authoritarian technology systems by repressive state actors to suppress citizens’ fundamental human rights goes beyond what is happening inside any one country’s borders. Increasingly, authoritarian actors are exporting these tools and know-how to new countries, strengthening their surveillance use and censorship capabilities.

The Open Technology Fund’s Information Controls Fellowship Program fellow Valentin Weber set out to track this diffusion and conduct a systematic analysis of its drivers and outcomes; through his research, Valentin found that, to date, over 100 countries have purchased, imitated, or received training on information controls from China and Russia.

Read The Worldwide Web of Chinese and Russian Information Controls in full here: English, Chinese, and Russian.

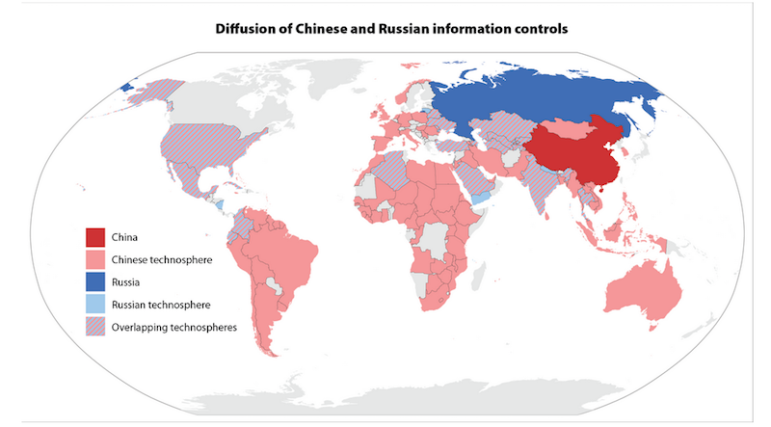

In some cases, the recipients were like-minded regimes where the information controls context is similar, including Venezuela, Egypt, and Myanmar. But with over half the world’s countries on the list, there were also many other (perhaps less suspect) countries in which similar investments were made: numerous African countries where connectivity is rapidly expanding, such as Sudan, Uganda, and Zimbabwe; several Western democracies like Germany, France, and the Netherlands; and even small Caribbean island nations like Trinidad and Tobago. All told, 110 different countries were found to have imported surveillance or censorship technology from Russia or China.

So, why have Russian and Chinese information controls spread to certain countries — but not others? What makes these controls more likely to spread to specific regions? And how does this international proliferation benefit the governments of Beijing and Moscow?

To answer these and other key questions, Valentin traced the diffusion of Russian and Chinese information controls and techniques through open source research, including data gathered from company reports, technical network measurements, newspaper and journal articles, and government-issued laws and regulations. Three different indicators (technology, imitation, and training) were employed to address the breadth as well as the depth of this diffusion. The more indicators discovered in a given country, the deeper these controls were deemed to have spread.

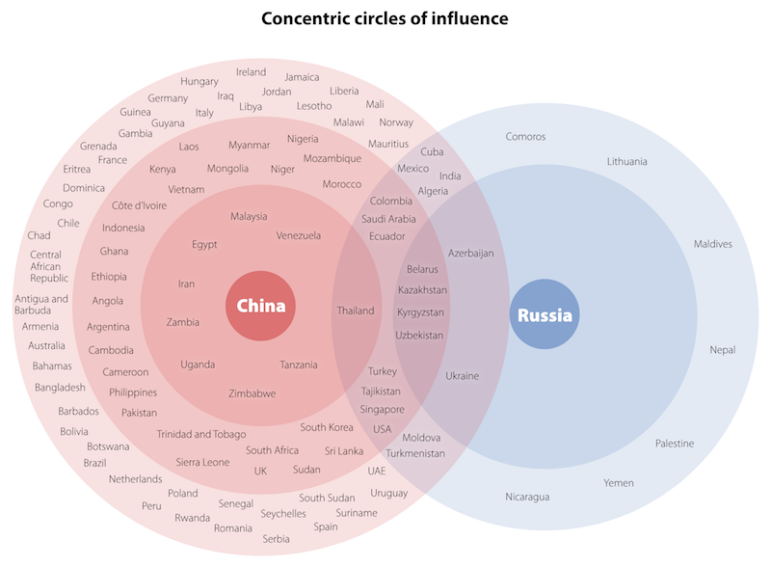

Based on the collected empirical data, Valentin found Russian and Chinese information controls spread most often to countries with hybrid or authoritarian regimes, particularly those with ties to China or Russia. Geographic proximity was determined not to be the primary variable in determining whether controls were likely to spread to a given country; instead, regime type and the extent of interconnectedness between the country and Russia or China best explained why diffusion occurred. Bilateral economic, political, historical, and social relations significantly helped to explain why Chinese and Russian information controls were more likely to spread to certain countries than others. For example, Chinese-exported controls were found to be most common in countries participating in the Belt and Road Initiative, while Russian-exported controls were most extensive in countries within the Commonwealth of Independent States.

The primary result of this vast diffusion was what Valentin calls the creation of Russian and Chinese “technospheres” — geographic areas within which political, economic, and intelligence-based advantages are conferred on the exporters of information controls. Politically, the proliferation of these controls reinforces and normalizes the ideologies of autocratic regimes like China and Russia. Economically, the diffusion of these systems creates new markets for the exporting nations (going so far as to foster security-industrial complexes within Russia and China). Intelligence implications and opportunities also abound within these technospheres for the countries exporting surveillance products.

China’s core technosphere — in which the diffusion of information controls was found to exist most deeply — consists of Egypt, Iran, Malaysia, Russia, Tanzania, Thailand, Uganda, Venezuela, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Russia’s core technosphere was slightly smaller: Azerbaijan, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

Substantial implications for free speech, media freedom, and human rights around the world exist due to the number and diversity of countries importing and using these information controls. The tools being imported from Russia and China are sophisticated — CCTV cameras with facial recognition technology, smart national identity cards, and intelligent databases for governments. The potential for abuse is strong and concerning, as is the chilling effect on populations that know these controls are in use.

In his report, Valentin recommends that it is therefore incumbent on democracies to restrict the use of these technologies within their borders and work to mitigate the potential for misuse whenever such controls are in place. While the diffusion of increasingly sophisticated surveillance technology from China and Russia to new countries over the past 13 years has been considerable, understanding what has been developed and deployed to date helps illuminate this trend and inform strategies to counter the further adoption of these tools of repression.

Valentin’s full-length report, The Worldwide Web of Chinese and Russian Information Controls, is available in English, Chinese, and Russian.

This article first appeared on the Open Technology Fund’s site and is reproduced here with permission.

The report’s author, Valentin Weber, is a PhD candidate in Cyber Security at the University of Oxford. He is a research affiliate at the university’s Centre for Technology and Global Affairs. His report is the result of a six-month fellowship with the Open Technology Fund.

The report’s author, Valentin Weber, is a PhD candidate in Cyber Security at the University of Oxford. He is a research affiliate at the university’s Centre for Technology and Global Affairs. His report is the result of a six-month fellowship with the Open Technology Fund.