The Great Mistake: Live in Mexico and Be a Journalist

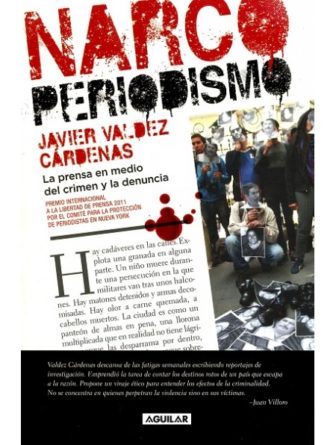

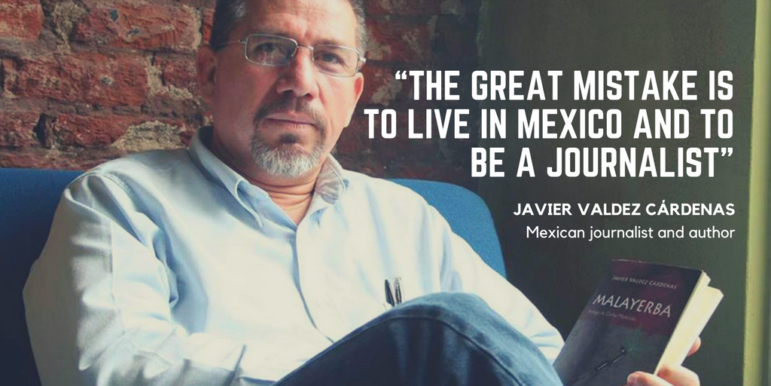

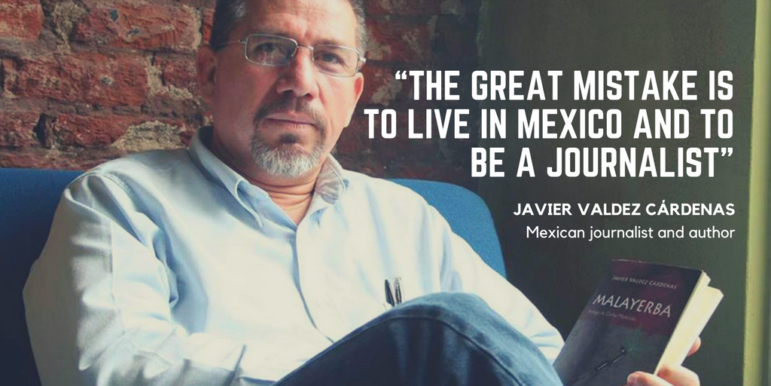

Editor’s note: In his 2016 book, Narco-Periodismo (Narco-Journalism), Javier Valdez Cárdenas wrote, “The great mistake is to live in Mexico and to be a journalist.” One year later — just a month ago — he was killed, becoming the sixth member of the Mexican press to be killed in a two-month period.

Editor’s note: In his 2016 book, Narco-Periodismo (Narco-Journalism), Javier Valdez Cárdenas wrote, “The great mistake is to live in Mexico and to be a journalist.” One year later — just a month ago — he was killed, becoming the sixth member of the Mexican press to be killed in a two-month period.

Mexico is one of the most dangerous countries in the world to be a working journalist. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reports that 25 journalists have been killed since President Enrique Peña Nieto took office in December 2012. Although their murders took place independently of each other, those targeted shared a commitment to documenting aspects of drug trafficking and political corruption. The Mexican government has been worse than silent: there have been almost no successful convictions of a journalist’s killer.

The government’s inaction and failure to protect the press endangers not only reporters but freedom of expression and even Mexico’s democracy. As members of the international press community, we stand with Mexico’s journalists and to urge the Mexican government to act. Please share this story widely and register your concern with the hashtag #ourvoiceisourstrength and #nuestravozesnuestrafuerza. Let Mexican journalists know they are not alone, and let the Mexican government know the world is watching and waiting for a solution.

Amid the accusations and insults President Donald Trump hurls at the U.S. media, it’s easy to ignore that there is a real, shooting war on the press — and it’s happening in Mexico.

In little more than the past two months, six journalists have been gunned down in various parts of the country. The newspaper Norte in the border city of Ciudad Juarez ceased to publish, saying the business of journalism had become too dangerous.

The most brazen case occurred Monday in western Sinaloa state, where journalist and author Javier Valdez Cárdenas, known for his investigations into the drug trade, was stopped by gunmen in his car and shot to death near the offices of the weekly Ríodoce, which he helped found in 2003. Sinaloa is home to Mexico’s powerful drug cartel of the same name, once headed by Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, who is in the United States awaiting trial.

Valdez had an international profile, recognized by both the Committee to Protect Journalists and Columbia University (with the Maria Moors Cabot Prize) for his work and courage to not be silenced in one of the most dangerous countries in the world to be a journalist.

His killing sent the message that no journalist in Mexico is safe. Valdez had no illusions about that. When I interviewed him last fall about his latest book, Narcoperiodismo, he told me he didn’t need any reminders that his work could cost him his life. “I don’t need them to call me and say, ‘Stop, or we’re going to kill you,’” he said. “I have to learn on every story how far I can go, what information I can’t publish … and I know if I cross the line they’re going to kill me.”

Mexico is a democracy. It’s not a country at war, at least not officially. Yet it ranks ninth in the world for number of journalists killed since 1992, ahead of Afghanistan, Rwanda and Israel and the occupied Palestinian territory, according to CPJ. But if you look at the numbers in just the past five years, Mexico is No. 1 — surpassing even Syria and Iraq — in noncombat killings that CPJ says are work-related or are under investigation for being work-related.

People generally assume these reporter killings are part of the general drug-cartel violence that has engulfed Mexico. That’s clearly a factor. But there’s another statistic that is often overlooked.

More than a third of all attacks on journalists in Mexico are carried out by some state actor, that is, a government, military or police official, according to the government’s own statistics. That number rises to 81 percent in the coastal state of Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico, where half of Mexico’s journalist assassinations have occurred in the past five years — including a killing and an attempted homicide in the past two months.

In Mexico, the deadliest terrain for journalists is where government and cartel interests intersect. Reporter Miroslava Breach was killed March 23 in the northern city of Chihuahua, shot eight times as she was leaving her home with one of her children. Three weeks earlier, Breach published an article about links between local mayoral candidates and organized crime.

The killer of journalist Marcos Hernandez Bautista in 2016 in southern Oaxaca state was a police chief.

Veracruz saw a spike in killings, intimidation and threats under former Gov. Javier Duarte, who fled Mexico near the end of his term (2010-2016), accused of money laundering and organized crime. (He was captured recently in Guatemala.) Attacks on the press in Veracruz wiped out nearly all critical reporting, guaranteeing Duarte the cover to rob the state of tens of millions of dollars for his own use.

Valdez agreed that the reporters had more reason to fear the government than the narcos, calling Mexico’s political class “intolerant, repressive and homicidal.”

In fact, Valdez became concerned for his safety in March after Ríodoce published a story about narco-political links and copies of the weekly disappeared, CPJ’s Carlos Lauría wrote Friday in the New York Times. “This is something different,” Valdez had told Lauría.

In an earlier interview, he had told me: “The political class … is where it is because the narcos protect it, narcos finance their campaigns, put them up as candidates and then as governors.”

Like all crime in Mexico, the vast majority of press killings go unpunished. Only two of 38 in the past five years have resulted in convictions. Most are never even investigated. But it makes sense when you consider that the state, which is charged with prosecuting the crimes, is also the suspect in a high percentage of attacks.

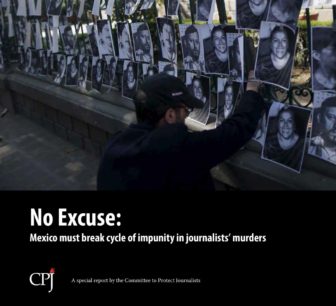

Several weeks ago, CPJ issued a report on the situation called “No Excuse,” urging the Mexican government to act with viable investigations and prosecutions of these killings.

Americans who take a free press for granted may not recognize the danger of a government using its powers to delegitimize and suppress media watchdogs. But Trump’s cries of “fake news” and “enemy of the people” give us the perfect opportunity to consider what can happen when the vitriol spins out of control.

I would never argue that the situation in the United States is anything close to what’s happening in Mexico. Still, Americans should care. A stable democracy in Mexico only benefits the United States, and a vibrant, independent press is a necessary ingredient.

Mexico is also an important reminder of what can happen if we become casual about our own right to free speech. After Trump’s “enemy of the people” remark, CBS anchor John Dickerson asked the President’s Chief of Staff Reince Priebus what he would say to Trump supporters, known to have acted out at rallies, “who might take license with the idea when the president says the press is the enemy and act on that declaration?”

“Certainly we would never condone violence,” Priebus said. But the fact that violence against the press even came up in this context is chilling.

Nor do I take lightly the Trump supporters who don T-shirts printed with the words “Rope. Tree. Journalist. Some assembly required.”

To some, it may be in jest. But given the events in the past few weeks in Mexico, and those journalists who have been lost to violence, I see how far it can go.

To view video of Katherine Corcoran interviewing Javier Valdez Cárdenas, click here. This op-ed was previously published in SF Chronicle and is reproduced here with permission.

Katherine Corcoran is the former Mexico-Central American bureau chief for the Associated Press and the Hewlett Fellow for Public Policy at the Kellogg Institute for International Studies at the University of Notre Dame. Reporting for this article was supported by the Alicia Patterson Foundation.

Katherine Corcoran is the former Mexico-Central American bureau chief for the Associated Press and the Hewlett Fellow for Public Policy at the Kellogg Institute for International Studies at the University of Notre Dame. Reporting for this article was supported by the Alicia Patterson Foundation.