“Screaming in the Desert”: The Investigative Reporters Exposing the Killers of Journalists in Honduras

Read this article in

Filming the documentary “Élites Criminales,” or “Elite Criminals.” Photo: Courtesy Dunia Orellana

When Honduran journalist Gabriel Hernández was killed on March 17, 2019, the Reporteros de Investigación (Investigative Reporters) team knew it should investigate the case. Hernández was walking toward his home in the municipality of Nacaóme, Valle department, when someone shot him six times.

The 54-year-old worked for the Valle TV channel and was the director and presenter of the program “El Pueblo Habla” (“The People Speak”), where he openly criticized the mayor and the deputies of the department. In 2015, he received threats and attacks from the police, but when he requested protection measures, they were denied. “Does not qualify,” was the official response, the investigative news site said.

This was denied by a representative from the General System of Protection, the government body responsible for protecting journalists and human rights defenders in Honduras, which told LatAm Journalism Review via email that the system had no record of threats against the reporter nor of requests for protection.

The investigation of his murder, which was followed by that of a second journalist, Edgar Joel Aguilar, on August 31, 2019, led Reporteros de Investigación to publish a series called “Sicarios” (“Hitmen”) in which the team investigate high-impact crimes against journalists and others.

“The series ‘Sicarios’ talks about how there are elites that are in collusion with organized crime in the country to murder journalists and important actors in the country,” explained Wendy Funes, director and founder of Reporteros de Investigación, in a documentary about the problem titled “Élites Criminales” (“Criminal Elites”). “The surprising thing about this is that ‘maras’ (gangs) and also some armed groups from the state are used.”

Screenshot: “Sicarios”

The documentary, which shows the main findings of “Sicarios,” as well as the work of Reporteros de Investigación in general, was released in a movie theater in the Honduran capital Tegucigalpa on December 8. It’s now available on YouTube. The project is part of a longer-term plan to make short films that reflect the danger journalists face in Honduras.

Investigating the murders and other dangers journalists face in the country has been a central part of the work of Reporteros de Investigación since it was created in 2017, Funes explained to LJR.

“We want to follow up on this [murders of journalists] because in reality what we believe is that if we do not investigate, no one else will investigate: neither the police nor the prosecution, nobody cares,” Funes said. “If the press doesn’t investigate, no one else will.”

Her statement is not far from reality. Killing journalists in Honduras does not seem to have consequences. In the last decade, more than 80 journalists have been murdered and according to the National Commissioner for Human Rights in Honduras (CONADEH, its acronym in Spanish), 97% of these remain unpunished.

Much of that impunity is because those paying for the hits aren’t being prosecuted. Based on leaked documents, the “Sicarios” series found “that there is a market of hitmen financed by elites in the country” according to Funes. She added that this is not only seen in crimes against journalists but also against leaders like Berta Cáceres, an Indigenous human rights defender, according to the criminal investigation of the case. “There is no punishment for them,” Funes said.

“The clearest criminal signature of the lineage of politicians who are feeding the hitmen is in the crime against journalist Aníbal Barrow,” says the first installment of the “Sicarios” series. “Five years after former head of criminal investigation Carlos José Zavala Velásquez found the bodies of the journalist and his driver, decapitated, burned, and dismembered, he testified before the Southern District Court of New York that ‘rumors were circulating that Barrow had been assassinated by order of highly ranked corrupt politicians.’ The evidence lies in file 1: 2015-cr-00174-439818 of that court. The officer identified [criminal organization] Los Cachiros as those responsible for Barrow’s death. However, he was reassigned and, therefore, could not follow up, his defense said before the Court.”

According to the “Sicarios” investigation, in the Barrow crime that occurred in 2013, only members of the “maras” were convicted despite the fact that they claimed in court to have worked with some politicians. Irregularities like this were also found in the Hernández murder, where according to some documents, the police allegedly omitted testimonies that involved politicians in the area.

The Investigative Reporters team

So far, according to Funes, not a single mastermind in a crime against journalists in the country has been convicted. That is why she is convinced that the little justice that can be achieved is through investigative journalism.

“I do believe that at this moment only those who investigate what is happening can save us,” Funes said. “Just as colleagues did with the murders of journalists and the El Comercio team [in Ecuador].”

“We live in a region marked by impunity,” Funes explained. “More than 30 years have passed, for example, since one of the most symbolic murders in Latin America, which is the case of Guillermo Cano [Colombia], and it is still not clear what happened to him… So I believe that only the work of the press can guarantee a bit of the right to the truth that relatives, and society in general, have.”

Obstacles for Journalism in Honduras

As its name indicates, Reporteros de Investigación is dedicated to conducting journalistic investigations and promoting that type of journalism. However, something that characterizes the team of five permanent journalists and almost 12 contributors is the emphasis on investigating crimes against journalists and in general everything that affects press freedom.

But journalistic work in Honduras faces other obstacles besides assassinations. In the series “Cárcel para la palabra” (“Jailed for Words”), for example, the team reports on a growing trend in the country, which consists of suing journalists for various crimes of defamation in such a way that they can be sent to prison.

David Romero was serving a 10-year prison sentence for crimes against honor and crimes of defamation constituting “injurias” (insults), according to C-Libre, an organization that promotes freedom of expression in Honduras. He died on July 18 of this year from COVID-19 after being hospitalized for 13 days.

“They learned from having taken David Romero to prison that it was more effective to accuse journalists of 30 crimes of defamation, of 100 crimes of defamation,” Funes said. “There is a journalist at the moment, Milton Benítez, who is accused of 30 defamation crimes. And if these penalties are combined, as they were with David Romero, he will go to prison.”

In addition to this trend, there is also the issue of disinformation that, according to Funes, is fostered by the government itself to discredit the press. Due to this environment, journalists have trouble covering a topic, they are harassed, insulted both physically and online.

“In the series “Cárcel para la palabra” we talk about all the risks of being a journalist and how we can expose ourselves to prison as journalists,” Funes explained. “There we reveal, for example, that there are exiled journalists, that there was a jailed journalist, who was David Romero, and that there are now 20 more accused. Also in the same series is the issue of disinformation.”

Reporteros de Investigación has felt these obstacles firsthand. A journalist from the team suffered a series of robberies in 2018, and in 2019 the site was the victim of cyber attacks, had its Facebook page blocked, and was even on the receiving end of smear campaigns. One tried to link the site with the “maras,” a fact it reported to the Protection Mechanism, according to Funes.

Given the investigative reports published by the site, the authorities have a strategy of ignoring them, according to Funes, “as if we did not exist.”

“I think it is good to make it visible, because as I said, the strategy is to make us invisible, and for our message to not reach the population,” Funes said. “And to denounce that there really is an operation of drug traffickers who are involved in politics, and yes, I am not afraid to say so. Here the drug traffickers are involved in politics and they have also been murdering journalists. And we did not know that until now, that we are going to the regions, and that people talk about it.”

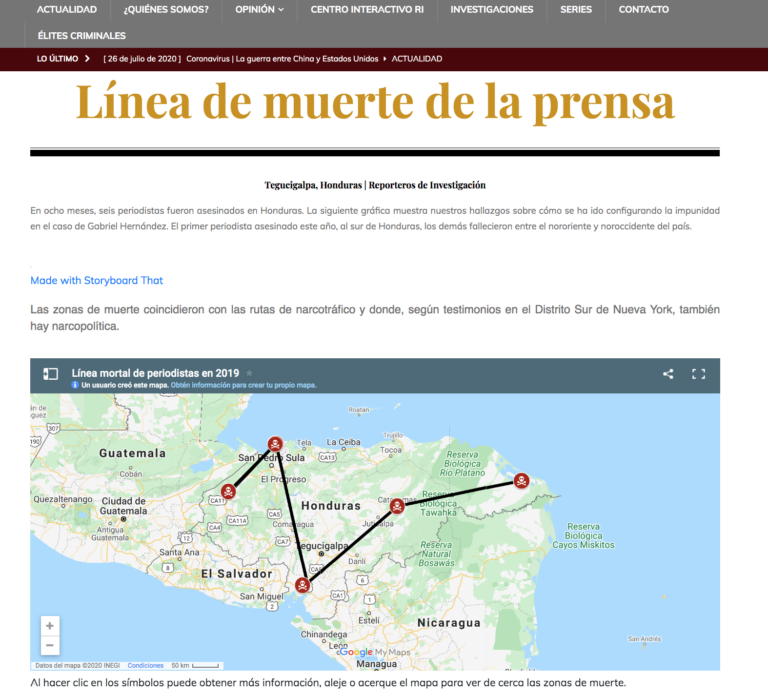

The situation of the press in Honduras has also been highlighted by the Office of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). In 2019, it publicly urged the state to investigate the crimes of Hernández and the journalist José Arita, although in its annual report of that year it indicated that at least six journalists were murdered in the country that year in relation to their work and added that “their material and intellectual authors have not yet been identified.” The Office of the Special Rapporteur also highlighted the large number of exiled journalists as well as the case of David Romero, who also had precautionary measures from the IACHR, and reiterated its call for the state to decriminalize so-called crimes against honor.

Image: Screenshot

However, for Funes, the support being received from other media outlets and from the international community is not enough given the level of violence experienced by journalists in the country. For that reason, she asks for other colleagues to join the investigations.

“The murders [of journalists] have continued” in Honduras, Funes said. After a decade of attacks, “last year we closed with 80 and this year there are organizations that speak of 85. So the murders continue, but it seems that nothing will happen… At an international level there is not much of an echo. Sometimes I feel like no one cares about Honduras, that we are alone, that we are screaming in the desert.”

For now, the commitment of Reporteros, as Funes says at the opening of the documentary, is “to open the eyes of the majority.” “We are committed at Reporteros to doing a different kind of journalism for this country.”

LJR asked the National Police and public prosecutor for comments, but did not receive a reply as of publication.

This story was originally published by the LatAm Journalism Review, a magazine published by GIJN member the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas at the University of Texas. It was written in Spanish and translated by Teresa Mioli. It is republished here with permission. A Portuguese version is available here.

Additional Reading

After Mexican Journalist’s Murder, Colleagues Come Together to Investigate

UNESCO: Still Widespread Impunity for Killing Journalists

Mexican Journalist Marcela Turati: “Don’t Abandon Us”

Silvia Higuera Flórez is a Colombian journalist who has written for the Knight Center since 2012. She reports on Latin America, human rights, and investigative journalism. She has worked with the Office of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and had work published by Colombia’s Vanguardia Liberal, The Miami Herald, and El Nuevo Herald in Miami.

Silvia Higuera Flórez is a Colombian journalist who has written for the Knight Center since 2012. She reports on Latin America, human rights, and investigative journalism. She has worked with the Office of the Special Rapporteur for Freedom of Expression of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and had work published by Colombia’s Vanguardia Liberal, The Miami Herald, and El Nuevo Herald in Miami.