Resistance, Solidarity, and Reporting in Mexico: Q&A with Marcela Turati

“She is a promoter and leader of collaborative projects. In one of those projects she investigated the 2010 execution of 72 mostly Central American migrants, and the forced disappearance of hundreds more, by drug traffickers and police in the deadly Mexican state of Tamaulipas. Her reporting revealed the hidden tragedy of massive disappearances in Mexico and exposed a vast number of clandestine mass graves in the country.” — Columbia Journalism School on Marcela Turati, July 2019.

The award-winning Mexican journalist and author Marcela Turati was recognized this time with the 2019 Maria Moors Cabot Prize for her professional excellence and for promoting better inter-American understanding with her reports.

The Columbia Journalism School has given the prestigious Cabot Prizes since 1938, honoring journalists on the American continent who stand out in the profession.

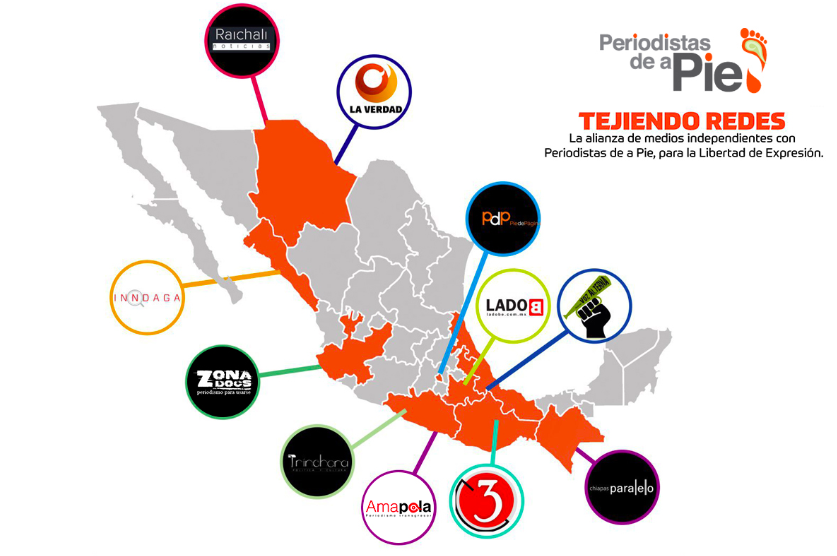

Turati, a native of the northern state of Chihuahua, has covered the war against drug trafficking in Mexico for several years, focusing on the victims of violence, on disappeared persons, their survivors and their families. In recent years, she and colleagues have founded the network Periodistas de a Pie and investigative site Quinto Elemento Lab. [Editor’s note: Quinto Elemento’s “El país de las dos mil fosas” (The country of two thousand graves) was the first place winner of the Javier Valdez Latin American Prize for Investigative Journalism at Colpin in Mexico City earlier this month.] Both groups seek to defend freedom of expression, support journalism, and obtain protection for Mexican journalists. Mainly, they support journalists who work in the most dangerous and poor regions of the country.

Likewise, with Quinto Elemento Lab, Turati and her colleagues train journalists in terms of techniques and innovative investigative angles, and give emotional and psychological support for all journalists who have been covering the country’s violence for years.

“So many years of violence burn, so many years of violence can make it so that your joy of living is diluted, they cause trauma, cause stress, make us change as people and what we want is to keep the heart open and clean, and to be able to continue ahead without getting used to this violence, but also to be prepared for this violence,” Turati said in a moving interview with the Knight Center leading up to the Cabot Prize ceremony.

The entire interview, which has been translated from Spanish, continues below. Responses have been edited for clarity and length.

When or how did you decide to become a journalist?

Well, in college. At first I wanted to study radio and in the final semesters, I took the subsystem workshop, which are like specialized classes, and for some reason I chose journalism, and in the classes I fell in love, I loved it. It seemed to me, I don’t know, that it came easy to me to write, I liked it.

I also had to write about the Sierra Tarhumara – I’m from Chihuahua – and that there was hunger and a campaign was made to help people, so I saw that there was a power there to help change things, right? And I also had very good teachers who had been, one of them, a war correspondent, and I really liked to hear their reporting stories. And, then, at the university it was at that moment that I got the little worm of doing journalism. We had a very good school newspaper called La Guardilla, and there I made my first steps.

Then, still in college, I had a little doubt, and I wanted to be in a human rights organization or be a journalist. I spent my last semester in the indigenous community, in a project, helping indigenous popular communicators to learn, but there I discovered that I am very desperate and that I liked changes to happen quickly, that the other was like a process that took too many years and that I liked to investigate a subject, touch on a subject and, of course, to talk about it and see, and try to make changes in a short period of time and that is why I decided, well, I chose journalism. And immediately, then, they hired me when I graduated, they hired me at the newspaper Reforma, so that defined my path.

When you think of all the people you’ve interviewed and all the stories you’ve covered, which ones would you say were the most interesting or with/from which did you learn more?

Well, something that did mark me, and that have been those that have left a mark on me in recent years, have been the victims of violence, the survivors, the families of the victims, the people who have survived the violence. So, for me, perhaps the people who have moved me the most, crushed [me], the ones from whom I learned the most, are the mothers, the sisters, the daughters of people who have been disappeared, because I see them fighting every day, looking for their relatives, trying different ways, changing laws, mobilizing, preparing themselves in legal matters, becoming almost private investigators, learning strategy…

I feel privileged to be able to accompany them and I feel that they also humanize me, right? When I see that they do all that for love and that it is done for love, and how they love their children, relatives who have been disappeared. And, well, I feel that. I know that they have really left a mark on me in recent years. I have learned many things from them, and, well, I am very grateful to them because I always say that they humanized me.

What does it mean for you to be a journalist in Mexico and what type of journalism do you do now?

Well, being a journalist in Mexico is a constant challenge. It is living in a country where, as I have said for a long time, and several of us say, we become war correspondents without leaving our land, where several of us decided to cover the violence from a more human rights approach, where we are in constant contact with the tragedy, with the victims, and also it challenges us all the time in how to tell these stories so as not to normalize them. How to continue telling.

For example, in my case, since 2008 or so I began to systematically cover victims of violence, to follow, to see their cases, to talk to people who were displaced, or people who have a disappeared relative, or survivors or witnesses of massacres, or relatives of massacred people, and the victims are thousands of thousands… And well, for journalists it has been — us journalists who cover those issues — it has been a constant challenge. It has meant becoming journalists and many other things: journalists who had to create networks to protect ourselves, train ourselves in physical security, digital security, and then, emotional security…

To give importance to being in community, to do it in [a] collective [way], to make us a community and strengthen ourselves, and take care of ourselves among many… That has been for me, during these years of coverage in Mexico, my work as a journalist but also my work as a promoter of networks or of collectives, so that different collectives organize themselves and, together, see how we take care of ourselves.

It has been a difficult time, because they have killed several beloved colleagues, well-known,; they kill many journalists, so that’s why we have that awareness that, in addition to being journalists, we have to somehow take to the streets or do journalistic projects to investigate these murders, to demand justice and to ask for an end to impunity. So, that has been a very important issue, that journalism in Mexico, in addition to everything, has been a victim of violence, and we are a profession that has had to organize to resist, to take care of each other, and to demand justice. Well, being a journalist in Mexico is a responsibility.

What feelings mobilize you when you remember your journalist friends who lost their lives for doing their job in Mexico?

That has also changed, that is, it has determined who I am and the decisions I have made. The first journalist I knew who was killed is ‘Choco,’ Armando Rodríguez, a journalist from Ciudad Juárez who was the one who took the pulse of the city. That murder was very difficult. When I had already founded Periodistas de a Pie with other colleagues, it was an organization that we created, first to organize ourselves and to better cover social programs, social issues, which later, due to violence, we changed to give workshops, trainings, and to accompany journalists. Journalists arrived from the most dangerous states, and we began to have contact and awareness of how dangerous it was to be a journalist in Mexico and in some regions. That determined my work as a journalist a lot, on the one hand, covering victims, but it was like having a double role, because it was also as a trainer and companion of journalists at risk, at the same time.

Then, we started, and it was from Armando’s case, when we realized that we all had to go out to protest because journalists in the states were alone, because they are the ones carrying the worst burden, because they are the ones who are most threatened, and because there was a lack of solidarity among the journalists who lived in Mexico City, although I am from Chihuahua, too…

Periodistas de a pie is a GIJN member organization in Mexico that provides journalists with training, network-building, and capacity-building. Photo: Screenshot

Then — with more murders that give you psychological tension — the friends, the colleagues, we did investigative missions. I was on three different missions, for two murdered journalists and for a journalist who was disappeared, trying to organize people or to support, produce workshops and support people in their process of putting together their own groups in the states where there was more danger to protect themselves, and train each other, and know what to do in cases of emergency. Also to articulate to social organizations, to leading journalists of these groups so that if there is an alert, first of all, they know what to do.

Well, we also had the murder of Regina Martínez, she was the Proceso correspondent in Veracruz. She was a very important investigative journalist who knew, and was investigating, narco-politics. Then there was the murder of Gregorio Jiménez. I didn’t know him, but his boss asked us for help because he had just been abducted. They had him — that is, for a month she did not know about him and it was a month of intense campaigns to ask for his release. And when he was killed we did this first investigative mission of his murder.

Then they killed Rubén Espinoza, the photographer. Well, he sent photos for the magazine Proceso from Veracruz as well, and went to Mexico City to ask for help. He asked us for psychological support, we helped him get a psychologist, and he was killed in a multi-homicide with other people, including Nadia Vera, a Veracruz activist, and that murder in Mexico City marked many of us. It was very important because it made us understand that there was no safe place, that the bubble we thought was Mexico City had broken, and that the murders could happen at home, and that we had to do more things, that what we had done until that moment had not been enough. We had to better organize ourselves.

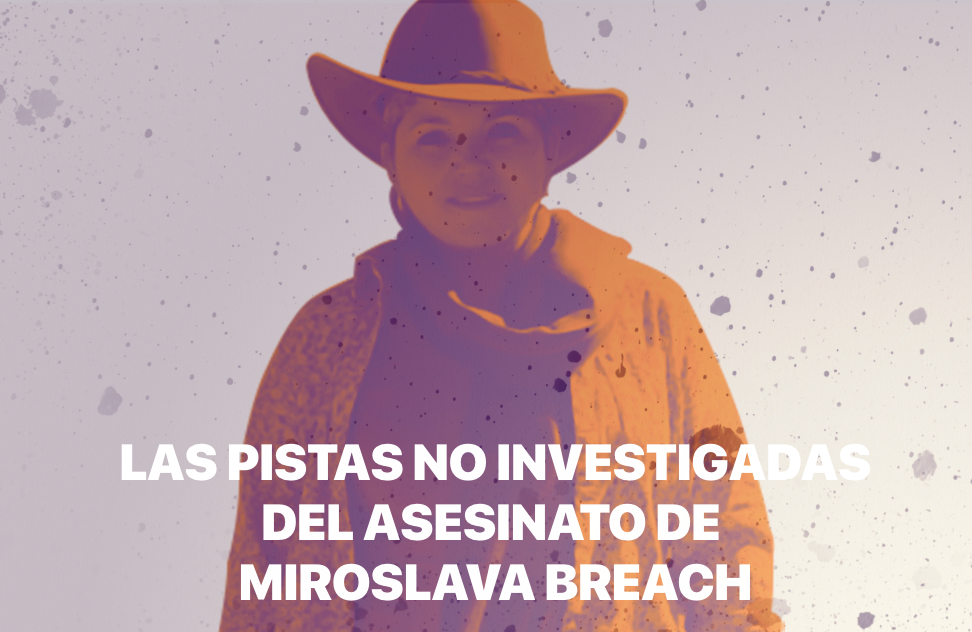

Then, in 2017 they murdered Miroslava Breach, whom I also knew. She was the expert journalist, the most important, the most recognized in Chihuahua… And then the other one that hit us in the heart was that of Javier Valdez, also a very good friend; I say he was like our older brother. He was that journalist who taught us to cover drug trafficking in the north, what could be done, what could not be done. He was our guide, he was a good friend. His murder also struck us because we saw that it doesn’t matter if you have international awards, no matter how well-known you are, everyone is at risk, and, well, Javier’s murder too, I don’t know, every murder has been difficult.

Mexican journalist Miroslava Breach was shot eight times outside her home while waiting to take her son to school. Image: Screenshot from Proyecto Miroslava

They have planted questions, doubts, challenges, how to continue, the process of organizing, what works, what doesn’t… Each one has defined, left a mark in different ways. It has brought me questions, doubts, pains, sorrows; it has also led me to meet impressive people, resilient, strong, brave colleagues, who continue to ask for justice.

I have thus seen how networks have emerged from all these murders, how life has come from death, how after they killed ‘Choco,’ the Network of Journalists of Juárez was created, with dear friends. How after Javier’s murder a whole commission of investigation is created, to follow up on this case, of journalists who honor him, the memory. How after the murders of Regina and Rubén, a collective is created in Veracruz, Voz Alterna, and a new media outlet is created. And how each murder, each aggression, or each disappearance of a journalist, instead of killing, although it gets some to leave the profession, also makes stronger the commitment of those who stay and these, in turn, create their networks.

What news report/topic do you think is the most relevant today?

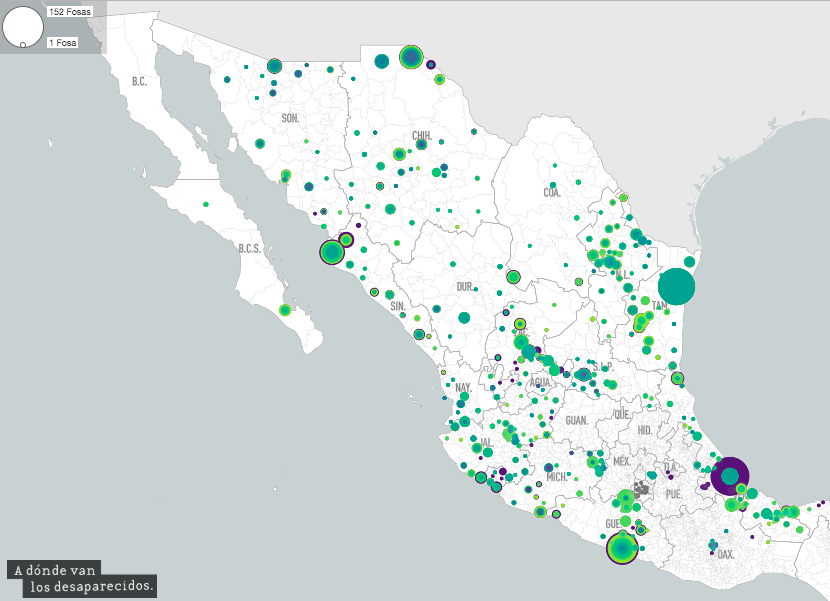

I would like to have more time now that I will return to Mexico, after several trips. Then start to chronicle the changes that are taking place in the country with this new government. The changes in social programs, the impacts it is having — that seems important to me. The other [topic], also for some time now, [is that] I and other colleagues have realized that we have to investigate the logic of the disappearance of people, not just saying that they are disappearing, but to begin to investigate further. This is what we have tried to do with the project El Mapa de Fosas (Grave Map) that we did, and with several of the projects we have. So, that’s it, investigate better, with new techniques, to start explaining certain massacres.

And the other issue that seems indispensable, urgent, important, that I regret not covering, are the caravans of migrants and everything that is happening right now with migrants, the borders, and on their route through Mexico, and these camps that have been created in the north and also the dangers that are being experienced in several regions along the way. Yes, the country is changing very rapidly and many people are disappearing on migration routes; there is too much abuse. And that there is a double talk [from politicians] and I would love to be covering it.

That is, there are too many things that seem urgent to me to cover and because of that I almost always work in a team because in a collaborative team we do it because — I don’t know, it has different scopes. I continue to collaborate with the magazine Proceso, but two-and-a-half years ago I founded Quinto Elemento Lab, which is a journalistic investigation and innovation laboratory where we help with reports from others. We accompany them from the beginning to the end, until they are published, and they are long processes because they are deep investigations of impactful issues, some of them risky.

It has also been like changing the speed compared to how I had been reporting. I no longer have to produce weekly articles, I no longer have to make articles for the day. Now there are longer processes to work on my projects, accompany those of others, and choose which are the most important issues at the moment. Well, it’s a challenge. That has been what I have dedicated this time to.

My agenda at this time, in addition to the topics that I would like to cover, is that I am dealing a bit more in journalism, in addition to trying to organize, trying for us to better organize ourselves as journalists from several regions and also for us journalists to cover the disappearances of people. Right now my concern has been to armor Quinto Elemento, how to make it a real power to be able to accompany journalists that arrive with their subjects that are often dangerous…

The project “A donde van los desaparecidos” (“Where Do the Disappeared Go?”) investigated Mexico’s mass graves. Image: Screenshot

And on the other hand, also, well part of the concerns or issues that I am dealing with is […] that we organize ourselves as journalists who cover disappearances, that we cover better, that we investigate better, that we think about them differently, that we think of the logic but also that the journalists who are following the exhumations, the graves, the relatives, and the victims of violence also have better conditions. Because so many years of violence burn, so many years of violence can make it so that your joy of living is diluted; they cause trauma, cause stress, make us change as people and what we want is to keep the heart open and clean, and to be able to continue ahead without getting used to this violence, but also to be prepared for this violence.

What does this Maria Moors Cabot award mean to you? How does it make you feel?

The Cabot Prize is very important for me and my career. It is a prize dear to me. When I studied and when I joined Reforma, it was the prize I liked, which was like magic, I don’t know how to explain it, but it was like a guide. The Cabot was given to people that I respected very much, to teachers that I loved very much and their work seemed impressive to me.

It also helped me discover people on the continent who did things, which was like a beacon to follow. So, I feel very honored that they chose me. I always think, then, that choosing me is also a nod, is seeing with love what we have tried to do so many years in Mexico. Because my work has always been collaborative, it has been collaborative for many years, it is working in a team, it is working with many people…

[This award] is a responsibility, it is a way of drawing attention to what is happening to us in Mexico, of what is going on, and of the fight, the effort, the struggle that Mexican journalists have undertaken to organize ourselves, to take care of ourselves, to train ourselves, to take care of each other, to create networks, to do joint investigations, and to continue doing journalism even in such diverse contexts. And on that side it is important. I do not know, I feel very honored and I have no words, really, to express what I feel with the Cabot, and I am so grateful for this interview.

This article first appeared on the Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas’ site and is reproduced here with permission.

Paola Nalvarte is a Peruvian journalist and documentary photographer living in Austin, Texas. She focuses on covering and writing about the Andes region.

Paola Nalvarte is a Peruvian journalist and documentary photographer living in Austin, Texas. She focuses on covering and writing about the Andes region.