Powering Up Geo-Journalism for Investigative Environmental Reporting

In some places, it was the gray dust visible in the water buckets that showed something was wrong, polluted by run-off water from the mines. In others, it was the toxic waste piles, left by mining companies to contaminate the groundwater.

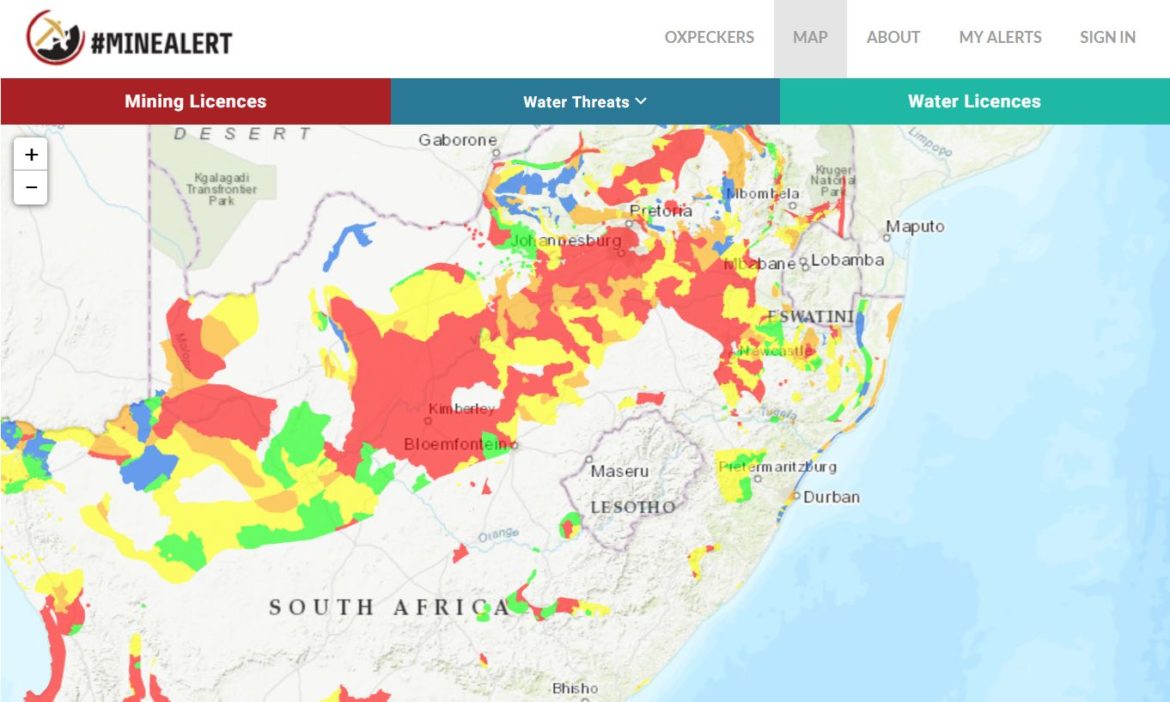

The investigation by Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism found that over 100 South African mines had been polluting local water systems as a result of water permit violations and inadequate environmental testing.

Raking through data on permit violations, Oxpeckers reached out to the companies flouting regulations to hold them accountable for their lack of transparency and disregard for community health and environmental welfare.

Digging deeper through parliamentary inquiries, they found that the government had allowed mining to continue even in areas where companies were failing to clean up their act. The result was polluted water discharged directly into the environment, unlined wastewater ponds, oil spills, and acid drainage run off, some of it in areas directly linked to the drinking water supply in nearby towns and villages.

Connecting these dots meant that activist groups like the Federation for a Sustainable Environment could file litigation against those complicit in the pollution of already-scarce water resources.

The mining investigation was an archetypal Oxpeckers story: as an outfit, the site focuses on a combination of data analysis and collaboration, using dynamic and interactive data visualization tools such as animated maps and infographics to tell compelling stories about the land and those accused of damaging it.

Building on a foundation of partnerships between donors, civil society, and advocacy groups, Oxpeckers has fostered long-term relationships that improve data collection and power investigations, leading to the exposure of eco-offenses and helping to hold perpetrators accountable.

Based in South Africa and founded in 2013 by veteran environmental journalist Fiona Macleod, who sits at the helm, Oxpeckers covers stories from across southern Africa and other regions, with high-profile stories on illegal wildlife trafficking and the effects of climate change. Mining, water, and pollution form other key subject areas.

As a data-driven journalism organization, accessibility of raw data is key to Oxpeckers’ work. It often makes the data tied to its reporting publicly available. It utilizes the openAFRICA and sourceAFRICA repositories for organizing and storing relevant data sources and documents for the public, and makes its own curated datasets from investigations associated with their geo-journalism tools #MineAlert, which monitors the mining sector, and #WildEye, a wildlife trafficking website, available to readers. Meanwhile, their journalism, often republished by Internews’ Earth Journalism Network and South Africa’s Mail & Guardian, has earned Oxpeckers several awards and the 20-member team was a finalist for South Africa’s prestigious Taco Kuiper Award.

Lifting the Veil on Mining Data

Although the South African media is freer than other countries in the continent, and stands at 31 of 180 of countries rated in the Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index, freedom of the press remains fragile; it is not unusual for journalists to be harassed over inquiries into government finances or corruption.

Meanwhile, some of the country’s major media owners have ties to industry and big business, and mining has always been a particularly sensitive subject since it comprises a significant portion of the country’s extractive sector (and an estimated 18% of gross domestic product).

Decades ago, this meant that the mining beat was often covered by financial journalists who worked closely with mining companies to report news on stock portfolios and investment. It was only when reports of water pollution, acid mine drainage, and toxic waste emerged that the subject began to be seen as ripe for investigative environmental journalism.

In response, policy makers and reporters began to highlight issues such as the regulation of mining companies and license procurement processes.

At Oxpeckers, #MineAlert, a geo-spatial data analytics tool, was created to track and share information on mining applications, licenses, and related issues with the aim of promoting both private and public sector accountability in mining.

The tool has enabled Oxpeckers to post the latest investigative developments and mining updates for users, including environmental and wildlife activists, NGOs, legal advocacy organizations and parliamentarians. These investigative reports have been used by advocacy groups for litigation and have been cited by parliamentarians pushing for transparency laws in the mining sector.

And the reporting has had a notable impact. A 2017 exposė on mine closures by Mark Olalde revealed that 124 mining companies that had been awarded mine-closing certificates had failed to rehabilitate the coal mines, leaving the communities nearby to deal with pollution, exposure to toxic gases, and depleted water resources.

This investigation led to the closure of several mines in water-scarce areas, and compelled the government to amend the law and force mining companies to become more transparent about their finances.

Another investigation, by Andiswa Matikinca, highlighted how the government’s fast-tracking of water use authorizations was putting communities at risk. The story revealed how a proposal to cut the amount of time mining companies need to wait for a license would drastically limit the time for risk and environmental impact assessments.

Building Investigative Tools in Partnership

Oxpeckers’ project-driven work means that its annual budget fluctuates from year to year, although major funders have included Open Society Foundation for South Africa (OSF-SA) and Code for Africa. Other supporters over the past year have included the Pulitzer Center, the African Network of Centers for Investigative Journalism, and the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project.

In 2018, Oxpeckers received $105,000 in funding with 85% coming from donors and the remaining 15% from collaborative geo-journalism projects supported by third-party media outlets. For 2019, funding increased to $120,000. In terms of web traffic over the past year, Oxpeckers has 40,000 users of their online tools and their stories have received over 70,000 page views.

A key partnership for the last five years has been with OSF-SA, which began to develop a grantee portfolio devoted to the country’s extractives sector, particularly mining, several years ago. The idea is that the funding helps promote transparency on mining licenses, operations, and commitments, bolstering the participation of mining-affected communities while simultaneously tackling corruption.

It was OSF-SA that granted Oxpeckers the seed funding to develop and launch the platform that would become #MineAlert.

“OSF-SA has always been drawn to beat reporting, niche journalism, and hot topic issues relating to economic crimes, land reform processes, and developments in political spaces,” said Nkateko Chauke, the program manager for OSF-SA’s Research and Advocacy Unit.

And while close relationships with organizations like the Federation for a Sustainable Environment and the Centre for Applied Legal Studies at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg are important, Oxpeckers is careful to draw a firm line between journalism and advocacy.

“#MineAlert lends itself to activism,” Macleod says. “We don’t want to come across as activists, though there is an activist edge to what we do. We leave the campaigning to the ‘experts.’”

The Future of Geo-Journalism

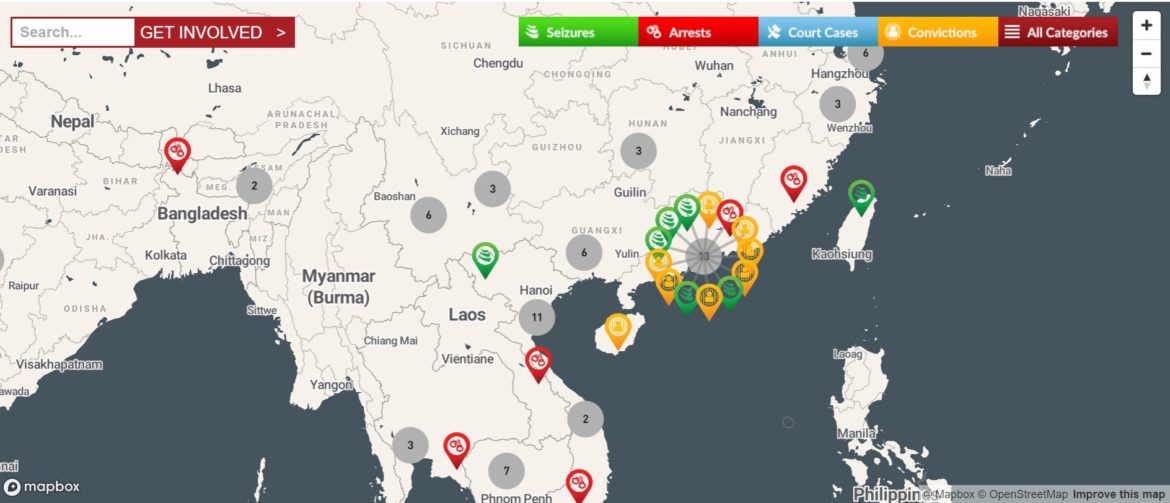

Expanding beyond its home base in southern Africa, Oxpeckers has been developing new tools to cover the illegal wildlife trade. Noticing a gap in how law enforcement agencies and legal systems handle wildlife crime across continents, Oxpeckers and the Earth Journalism Network launched the wildlife trafficking website #WildEye last year.

Both the European page and #WildEye Asia, which was launched this year, track information on seizures, arrests, court cases, and convictions collated by Oxpeckers from thousands of entries relating to wildlife crimes across the world.

The #WildEye map datasets are available upon request, but other datasets tied to exposés on illegal wildlife trade can be immediately downloaded by any user. Some of those datasets include details compiled from the illegal ivory trade across Europe and the price list of reptiles illegally sold online which was provided by a trader in Africa.

The platform enables users to monitor illegal wildlife trade throughout Asia with icons on the mapping interface containing information about what type and how many products were seized, or who was arrested, and what was their punishment. The map reveals stories like the fisherman arrested in Malaysia with 4,000 protected turtles, or the Chinese police investigation into a trafficking ring caught with 13,410 wild animal carcasses and 22,935 air gun bullets.

One of the first #WildEye Asia investigations, by Hong Kong-based journalist Bao Choy, discovered that lenient punishments for trafficking pangolin — a toothless, scaly mammal native to Asia and Africa — through China are unlikely to deter perpetrators from engaging in trafficking. Choy’s reporting shows that of the 34 criminals convicted of trafficking pangolin since late 2019, nearly half avoided prison despite the law mandating up to a three-year jail sentence and a fine.

Recognizing that human consumption of pangolins has been linked to the outbreak of COVID-19, her data-driven investigation highlighted the need for an overhaul of wildlife crimes legislation and enforcement.

Although the problems are huge, Macleod sees that Oxpeckers has had an impact. “Hard-hitting results typically come from the reports we produce, and though we can be a bit of a thorn-in-the-side, we are listened to by people in government who have good sense,” she says.

Environmental Resources on GIJN

Climate Crisis: Ideas for Investigative Journalists

Climate Change: Investigating the Story of the Century

Guide: Covering the Extractive Industries

Gregory Francois is a writer, research consultant, and a recent Master of Public Administration in Development Practice graduate from Columbia University. A former wildlife biologist, he lives in New York City and has consulted for the United Nations Development Programme.

Gregory Francois is a writer, research consultant, and a recent Master of Public Administration in Development Practice graduate from Columbia University. A former wildlife biologist, he lives in New York City and has consulted for the United Nations Development Programme.

Shruti Kedia is a policy analyst and a Master in Public Administration candidate at Columbia University. A former journalist, Shruti lives in New York City and works with Precision Agriculture for Development and the United Nations Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs.

Shruti Kedia is a policy analyst and a Master in Public Administration candidate at Columbia University. A former journalist, Shruti lives in New York City and works with Precision Agriculture for Development and the United Nations Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs.