Image: Screenshot

Pegasus Project Reveals Added Risks for Corruption Reporters

Read this article in

Exposing those who abuse power for personal gain is a dangerous activity. Nearly 300 journalists killed for their work since CPJ started keeping records in 1992 covered corruption, either as their primary beat, or one of several.

The risk was reaffirmed this month with the release of the Pegasus Project — collaborative reporting by 17 global media outlets on a list of thousands of leaked phone numbers allegedly selected for possible surveillance by government clients of Israeli firm NSO Group. According to the groups involved in the project, at least 180 journalists are implicated as targets.

NSO Group denied any connection with the list in a statement to CPJ; it says that only vetted government clients can purchase its Pegasus spyware to fight crime and terrorism.

Among the outlets analyzing the data is the global journalism network Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), which, as of July 29, had listed 122 of those journalists on its website.

Not all of those focus on corruption, Drew Sullivan, OCCRP co-founder and publisher, told CPJ in a recent video call. But several of OCCRP’s own partners in corruption reporting featured, he said, and he listed people who have worked for Azerbaijan’s independent outlet Meydan TV and Hungary’s investigative outlet Direkt36 as examples.

“People who are looking at problems with these administrations — which tend to be somewhat autocratic — in a lot of countries they were perceived as enemies of the state because they were holding governments accountable,” he said.

At least four corruption reporters whose cases CPJ has been tracking for years — in Mexico, Morocco, Azerbaijan, and India — appeared in the Pegasus Project reporting as possible spyware victims. Their inclusion in the project adds a new dimension to their stories of persecution, suggesting governments are increasingly willing to explore controversial technology as yet another tool to silence corruption journalism.

Here’s how the Pegasus Project revelations have shed new light on these four cases:

Freelance Journalist Cecilio Pineda Birto, Killed in Mexico

What we knew: Pineda endured death threats and a shooting attempt to continue posting on crime and corruption to a news-focused Facebook page he ran, but was gunned down at his local car wash in 2017. He was one of six journalists killed in retaliation for their reporting in Mexico that year.

New information: Pineda’s phone number was selected for possible surveillance a month before his death. He had recently told a federal protection mechanism for journalists that he believed he could evade threats because potential assailants would not know his location, according to the Guardian.

The government’s response: Mexican officials said this month that the two previous administrations had spent $300 million in government money on surveillance technology between 2006 and 2018, including contracts with NSO Group, according to The Associated Press. CPJ emailed Raúl Tovar, director of social communication at the office of Mexico’s federal prosecutor, and Jesús Ramírez Cuevas, spokesperson for President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, for comment on the use of spyware against journalists, but received no response.

Le Desk Reporter Omar Radi, Imprisoned in Morocco

What we knew: On July 19, 2021 — as many of the Pegasus Project stories were still breaking — a court sentenced Radi to six years in prison on charges widely considered to be retaliatory. He was jailed one year earlier, possibly to prevent completion of his investigation into abusive land seizures. Like fellow Moroccan journalists Taoufik Bouachrine and Soulaiman Raissouni, who are serving sentences of 15 years and five years, respectively, Radi was convicted of a sex crime, which journalists told CPJ was a tactic to dampen public support for the accused.

New information: Amnesty International had already performed forensic analysis of Radi’s phone in 2019 and 2020, and connected it to Pegasus spyware, as outlined in the Pegasus Project reporting. Now we know that Bouachrine and Raissouni were also selected as potential targets, according to Forbidden Stories.

The government’s response: The Moroccan state has instructed a lawyer to file a defamation suit against groups involved in the Pegasus Project in a French court, according to Reuters. CPJ requested comment from a Moroccan justice ministry email address in July but received no response. CPJ’s past attempts to reach someone to respond to questions about spyware at the ministries of communications and the interior were also unsuccessful.

Khadija Ismayilova, formerly imprisoned in Azerbaijan, was targeted by Pegasus spyware from 2019 to 2021 . Image: Courtesy Aziz Karimov

Investigative Reporter Khadija Ismayilova, formerly Imprisoned in Azerbaijan

What we knew: Ismayilova, a prominent investigative journalist, is known for her exposés of high level government corruption and alleged ties between President Ilham Aliyev’s family and businesses. She was sentenced to seven and a half years in prison on a raft of trumped up charges in December 2014, and served 538 days before her release.

New information: Amnesty International detected multiple traces of activity that it linked to Pegasus spyware, dating from 2019 to 2021, in a forensic analysis of Ismayilova’s phone after her number was identified on the list. Ismayilova subsequently reviewed other Azerbaijani phone numbers identified by the Pegasus Project and recognized some belonging to her niece, a friend, and her taxi driver, OCCRP reported.

The government’s response: CPJ requested comment from Azerbaijan state security services via a portal on its website on July 28 but received no response. CPJ’s request regarding the alleged surveillance of Meydan TV journalist Sevinj Vagifgizi last week was also unacknowledged.

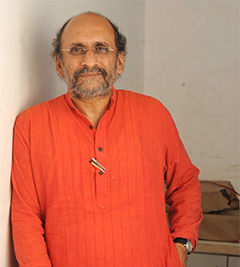

Image: Courtesy Guha Thakurta

Economic and Political Weekly Journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurta, subject to Legal Harassment in India

What we knew: Guha Thakurta, a journalist and author, has faced a protracted criminal and civil defamation suit dating from 2017, along with three colleagues at the academic journal Economic and Political Weekly — and was recently threatened with arrest when he refused to attend a hearing across the country during the pandemic. That suit — brought by the Adani Group conglomerate following an article that described how the company had influenced government policies — was one of several legal actions he has faced, which he characterized to CPJ as an intimidation tactic, and a way to harass reporters.

New information: Amnesty International detected forensic indications connected to Pegasus spyware in an analysis of Guha Thakurta’s phone, dating from early 2018. In a personal account published by Mumbai daily The Free Press Journal, Guha Thakurta noted he had been writing about Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the governing Bharatiya Janata Party’s use of social media for political campaigning at the time. He was also investigating a wealthy Indian business family’s foreign assets. But he still didn’t know why his phone was apparently tapped.

The government’s response: Ashwini Vaishnaw, the minister for information technology, has called the latest revelations about Pegasus “an attempt to malign Indian democracy,” and said illegal surveillance was not possible in India, according to The Hindu national daily. CPJ emailed Vaishnaw’s office for comment, but received no response. A former Indian government official has told CPJ that Pegasus is “available and used” in India, and a committee was formed to investigate alleged Indian spyware targets in 2020. But CPJ was unable to reach someone to confirm the status of that committee in January this year.

This article was written by Madeline Earp and was originally published by the Committee to Protect Journalists. It is republished here with permission.

The Pegasus Project was coordinated by GIJN member Forbidden Stories, a France-based nonprofit organization.

Additional Resources

Tips to Uncover the Spy Tech Your Government Buys

How Journalists Can Detect Electronic Surveillance

Mexico Wages Cyber Warfare Against Journalists

GIJN’s Guide to Partnerships and Collaborations

Madeline Earp is a consultant technology editor for CPJ. She has edited digital security and rights research for projects including five editions of Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net report, and is a former CPJ Asia researcher.

Madeline Earp is a consultant technology editor for CPJ. She has edited digital security and rights research for projects including five editions of Freedom House’s Freedom on the Net report, and is a former CPJ Asia researcher.