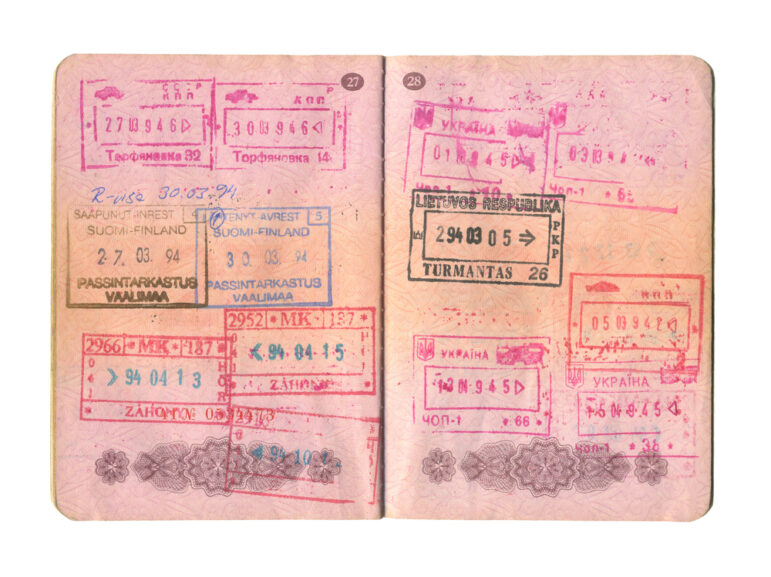

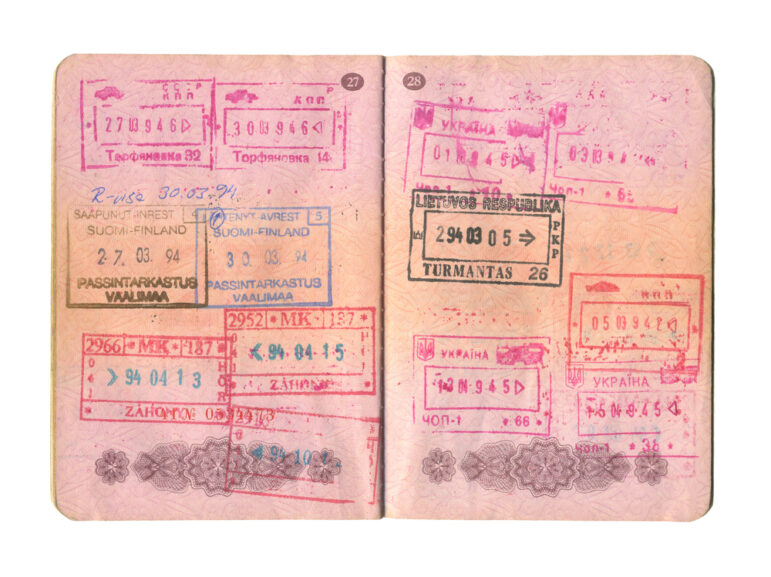

Passports often contain a treasure trove of information — and can help reporters trying to investigate the ownership of offshore companies and trusts. Image: Shutterstock

Passports Are Key to Uncovering Offshore Secrecy — We Use Machine Learning to Find Them Efficiently

Read this article in

Passports are often the key to unlocking secret ownership of offshore companies and trusts, but finding them among millions of leaked documents can be challenging. To streamline this process, we partnered with machine learning (ML) scientists from the AI Journalism Resource Center at OsloMet University and the Norwegian public broadcaster NRK to develop a passport detection tool.

This tool partly automates the identification of documents containing passports and extracts key information — such as the name of the passport holder, the nationality, and date of birth. This data is all held in the Machine Readable Zone (MRZ) — the two lines of text, letters, and code on the bottom of a passport photo page.

The ability to scour through that information allows data journalists to validate and efficiently share their findings with reporters, generating higher quality leads than before.

How Does Passport Detection Help Investigative Reporters?

Passports are often a critical part of the jigsaw for investigative reporters digging into ownership of offshore companies and trusts. They are often the missing link when investigating hidden entities’ ownership in secret jurisdictions. Journalists regularly use them to identify end clients of offshore service providers during investigative projects involving massive data leaks, as seen during ICIJ’s collaborative investigations exposing offshore secrecy like Pandora Papers, Panama Papers, and Paradise Papers.

In the Pandora Papers investigation, ICIJ and its media partners sifted through millions of documents to unearth the linkages between offshore companies, trusts, and the people connected to them across dozens of countries. In the first months of the investigation, ICIJ’s data team worked on providing lists of client names to media partners so that journalists could efficiently find leads.

The team reviewed thousands of pages of corporate records to eventually identify offshore dealings of 36 current and former world leaders and more than 300 other current and former public officials and politicians around the world. Passports were an important part of the puzzle.

“Passports inside large document leaks are an invaluable resource for finding individuals of public interest and for parceling out work among partners from many different countries,” explains Agustin Armendariz, senior data reporter at ICIJ. “Country lists of passport owners and beneficial owners are often the best starting point for reporters new to a leak to begin searching for a story relevant to their audience.”

However, locating and reviewing such documents is often a daunting task, akin to finding a needle in a haystack.

Why Can Passport Detection be a Hassle?

The machine readable zone, highlighted in red in this mock-up, contains key passport data, such as the name of the passport holder, the nationality, and date of birth. Image: ICIJ

While powerful, our previous workflow to identify passports in a massive amount of leaked documents proved to be both cumbersome and sometimes unreliable.

To find passports, journalists used Datashare, ICIJ’s open source search engine for documents linked to a particular investigation, performing two kinds of search queries. They either searched for keyword terms commonly found inside passports such as country names, “date of expiration,” “place of birth,” “passport no.,” “visa…” etc. Or hunted for common passport file names, such as “passport.pdf” or “passport.jpg.”

To improve accuracy, they could restrict the search to images and PDF file types, which are typically used to store passport scans, but both methods lacked robustness and were inefficient.

On the one hand, many passports were missed, since files containing passports are not always named as such explicitly. Furthermore, due to variable scan quality, text extraction on Datashare (which is powered by OCR, or Optical Character Recognition) can struggle to correctly extract the passport text, reducing the number of search matches. A further problem was that a lot of the passport keyword terms are also found in non-passport documents, triggering false positive matches.

Identifying passports using this workflow often required weeks of careful review, scrolling through thousands of document pages hoping to find actual passport scans.

How Did Our Machine Learning Collaboration with Researchers Help?

The goal of our collaboration with OsloMet and NRK was to leverage state-of-the-art Computer Vision algorithms to speed up and partly automate the passport detection process.

How does it work? To detect passports in documents, the files are first converted into images, then passport scans are detected inside documents using the open-source YOLO object detection model. When a passport is detected, the tool reads its Machine Readable Zone (MRZ) using a tailored OCR, capturing essential details such as the passport holder’s name, date of birth, passport number, country, and date of issuance.

Accurately extracting passport information and ensuring no passport is missed was still challenging. The YOLO model, originally trained for generic object detection, had to be fine-tuned to detect passports specifically.

The OsloMet and NRK team spent months reviewing and annotating documents shared by ICIJ, training models, and calibrating detection thresholds for optimal performance. Using a large and diverse dataset of passport images, we estimated that the model can recover 100% of passport pages found inside documents with a precision rate of 86%: only 14% of the images classified as passports are false positives.

How Did We Integrate This Into Our Workflow?

To integrate the model provided by researchers into our investigation workflows, ICIJ turned it into a fully-fledged service that can be deployed and run on servers processing up to 500 document pages per minute on a machine with a 16GB memory GPU (the service code is open source while the model is not publicly available for confidentiality reasons).

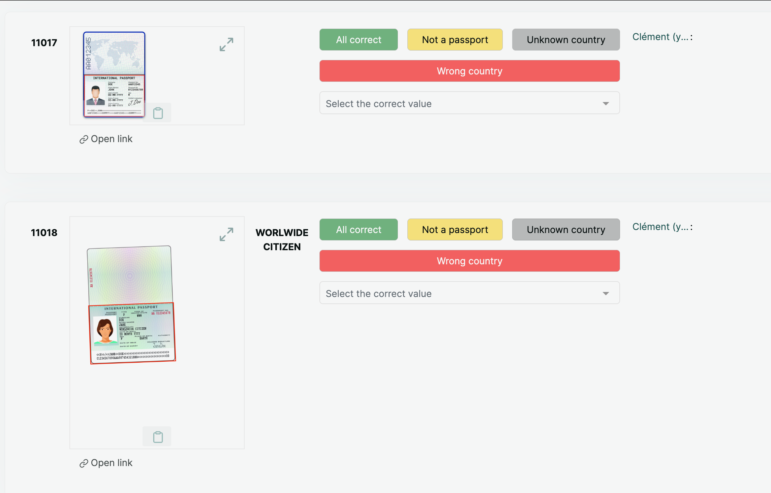

After the tool identifies potential passports and reads their machine readable zone, predictions are uploaded to the Prophecies fact-checking platform. Team members can review and correct predictions — mock-up documents are reviewed here. Image: ICIJ

When the passport detection is complete, the tool’s predictions are reviewed by ICIJ’s data team using Prophecies, our open source fact-checking platform. Thanks to the model’s high precision, the vast majority of images detected as passports are actual passport scans, making the review more efficient. After validation, ICIJ’s data team tags documents that contain passports in Datashare, allowing them to be used by the reporting team immediately.

So far, we have run the tool to classify hundreds of thousands of Datashare document pages. The tool not only made it possible to detect passports more easily and efficiently, it also allows us to perform passport detection more systematically. We are also exploring ways to kickstart automated entity resolution — matching documents to actual individuals — using passport information extracted by the tool.

As an example, during an ongoing investigation, ICIJ’s data team accurately identified around 500 passport scans out of more than 110,000 documents. We first used Datashare to narrow down the search to 75,000 documents with images, and then relied on the tool to detect about 1,000 images identified as passports. Each prediction was reviewed three times by different journalists using Prophecies, through multiple validation rounds.

After removing duplicates and keeping only pages with country information, about 500 unique passports and their country of issuance were finally identified. The workflow successfully reduced the task of analyzing more than 110,000 documents to just 3,000 targeted reviews. Delegating the detection process to an algorithm allowed us to save precious hours, preserving data journalists’ time for high added-value tasks such as fact-checking.

“The passport identification tool is an extremely fast way to sift through large document sets and quickly identify potential passports,” says Armendariz. “Investigators can then quickly identify any people of public interest in the collection of passports as well as identify sections of the leak to comb through by hand.”

For now, the tool’s model is only available to ICIJ staff, members, and partners for security and confidentiality reasons, however, we believe it could benefit other journalistic organizations. We are currently discussing the next steps to share and detail the methodology used to train the tool’s model, allowing other organizations to train their own model with their own data.

How Do We Maintain Confidentiality and Security?

While being very powerful for investigation purposes, passport data is also highly sensitive and, of course, confidential. To ensure the protection of our sources and of the data we receive from them, we take privacy and security very seriously — as we always do when working with leaked data. No data left our infrastructure during the development of the project or while using the tool, and we didn’t rely on third parties. Our infrastructure’s security relies on different pillars involving technical solutions as well as user training. ICIJ staff members or partners working on the project are bound by non-disclosure agreements.

Because machine learning models are subject to Membership Inference Attacks, we decided not to publish and share the model’s weights, as it could have helped attackers learn which passports the model was trained on.

Machine Learning With a Human in the Loop

Developing the passport detection tool showed that relying on machine learning with a human in the loop can help reporters efficiently address critical investigative journalism challenges. Collaborating with partners from academia proved to be incredibly fruitful in implementing these state-of-the-art machine learning solutions. We are extremely grateful to our partners for their support and are already collaborating with them — and other academic partners — on new projects, exploring ways to combine data journalists’ expertise with the latest advances in this field.

Clément Doumouro is a machine learning engineer at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), where he focuses on integrating machine learning tools and algorithms into Datashare, ICIJ’s search engine, and supporting journalists in analyzing documents during their investigations. He also collaborates with academic researchers to ensure ICIJ benefits from the latest advancements in machine learning. Before joining the ICIJ, he studied artificial intelligence and robotics before working as a machine learning engineer for Collective Thinking and Sonos, where he specialized in natural language processing and understanding, making sense of human oral and written language.

Clément Doumouro is a machine learning engineer at the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), where he focuses on integrating machine learning tools and algorithms into Datashare, ICIJ’s search engine, and supporting journalists in analyzing documents during their investigations. He also collaborates with academic researchers to ensure ICIJ benefits from the latest advancements in machine learning. Before joining the ICIJ, he studied artificial intelligence and robotics before working as a machine learning engineer for Collective Thinking and Sonos, where he specialized in natural language processing and understanding, making sense of human oral and written language.