My Favorite Tools with South African Investigative Journalist Susan Comrie

Susan Comrie helped expose one of the largest political scandals in post-apartheid South Africa. Photo: amaBhungane

For GIJN’s My Favorite Tools series, this week we spoke with Susan Comrie, an investigative journalist at the South African investigative journalism center and GIJN member, amaBhungane.

Comrie has a long established career in television and print investigations in South Africa. After pivoting from freelance entertainment to more in-depth features for the Daily Voice newspaper, Comrie joined South Africa’s leading investigative journalism television show, Carte Blanche, where she helped expose dodgy mining deals. She then moved to the weekly newspaper City Press, where she first started covering the Guptas, the wealthy Indian-born family whose ties to former South African President Jacob Zuma became a major corruption scandal.

It was with amaBhungane — which Comrie joined in 2016 — that her investigations of the Guptas, the intricacies of their lucrative deals with government departments, and the depths of their political network, helped expose one of the largest political scandals in post-apartheid South Africa. #GuptaLeaks — a collaborative investigation involving five organizations which won the Global Shining Light Award in 2019 — dug into every corner of the Gupta empire, from their dealings with now defunct PR firm Bell Pottinger, to the corrupt agricultural program that left struggling farmers destitute, to their contracts with South Africa’s rail and electricity utilities, and ultimately exposing their influence over Zuma and his cabinet, now known in South Africa by the shorthand “state capture.”

At amaBhungane, Comrie has also traced alleged links between local corruption and international institutions including Deloitte, SAP, and McKinsey. The independent investigative newsroom grew out of the investigations unit at South Africa’s Mail & Guardian newspaper and became a nonprofit in 2010. Named for the beetle that digs through dung, amaBhungane sees its role as “fertilizing democracy,” with the small team publishing their stories for free to the public.

Comrie says many of her investigations began simply by poring over public records. “A lot of the time it’s a case of being able to take the data and then understand the narrative that flows from that data and come up with a hypothesis that one can then test,” she said.

Here are some of Comrie’s favorite tools:

Excel

“Whenever I speak to journalism students, the one piece of advice I give them is, ‘make peace with Excel.’ One of the main things we use it for is building timelines to track complex investigations and manage evidence. There are some topics and companies that multiple journalists have worked on over several years, so having a timeline that keeps being built on is a great way of preserving institutional memory. Excel is also an excellent way to spot patterns or potential connections between what at first could look like unrelated events, tracing money flows, and spotting commissions and kickbacks.

“So if I’m looking at a story where there were multiple different deals that are all being done by the same consulting company — for example a story we did on Deloitte and our main power utility, Eskom — we create one timeline, but each deal has its own ‘sub-timeline,’ so you can filter the data according to each deal.

“Identifying patterns in money flows can be a lot of trial and error, so Excel helps when we’ve been working on long-term investigations. When we were looking at the Gupta Empire, we started to get a sense of how they would pay and move what appear to be kickbacks through money laundering vehicles. We would look at percentages of different figures and use Excel to give you percentages so that you can suddenly see, ‘Oh wait a second, that’s exactly 55% of this amount, maybe there’s a connection there.’

“The timeline helps enormously because you can suddenly start to see how money bounces in at one point, and bounces out at another seemingly unrelated point a few days later. Sometimes it’s people using strange little codes and acronyms that one can start to pick up more easily because you’ve got it all in one place. Timelines also help us figure out the narrative, or by highlighting something that requires further investigation and just helping us to join the dots. I even occasionally use Excel to structure a narrative — to move pieces of a story around — but that feels like a new category of nerdy. For writing introductions and structuring I actually find a transcription tool like Otter.ai more useful – I like to dictate introductions out loud, often while I’m driving or going for a walk, so it’s a really useful tool.”

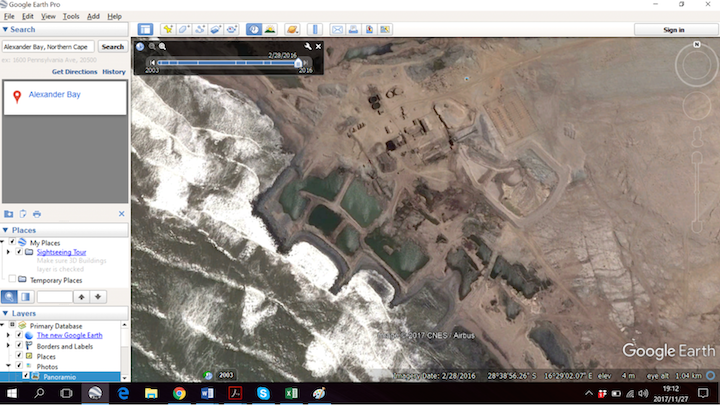

Google Earth and Sentinel Hub

“The desktop version of Google Earth Pro allows you to go back in time, while Sentinel Hub gives you more frequent pictures of what’s going on on the ground. Both are great for mining stories because mines are hard to access and often in remote places, which makes initial desktop research much easier.

“It’s also incredibly helpful when looking at power stations. In terms of the National Key Points Act [South African legislation which restricts access to areas declared state key points], one needs to be very careful about going near power stations and what you film near them. It’s also just bloody difficult driving between massive coal trucks in one’s teeny-tiny car. So it’s really helpful if you can do those initial checks [with satellite imagery].

“That being said, there’s just no substitute for actually going out there. I’m always amazed how far you can get simply by turning up at the gate and asking to go in or by following coal trucks. I like the combination of that — you can instantly access really remote places [through satellite data] but that it’s a first step in an initial assessment to actually going there.

“With Google Earth Pro and Sentinel Hub, the ability to go back in time is so helpful. A colleague of mine used it to show the effects of ‘coffer dam mining’ on the west coast [of South Africa]. It’s in an incredibly isolated place and he was able to show, through really basic Google Earth photos, how these mining areas had been built out into the sea before the mine had been granted a permit. Often, you’re going to have communities coming to you saying, ‘Our land has been polluted by this mining company.’ But there’s such a gap in power dynamics and the technology that people living there are going to be able to access, so being able to use that technology to look back at what has happened is really helpful.”

OCR Tools

“We use a lot of public records. Often the best stuff is buried in the annexes and you don’t always immediately know what you’re looking for. Which is why we try to run all those records through an OCR tool [optical character recognition, or image to text converter] and keep them in a central database that multiple members of the team have access to. We would use either OCRKit or Adobe Acrobat Pro. Sometimes it takes years to join the dots in an investigation, so it’s really useful to have access to old records that may contain evidence you missed the first time around.

“Our big experience of making sense of large troves of documents was with the #GuptaLeaks. Another was our work on Regiments Capital, the local partner of global consulting giant McKinsey. We found evidence that Regiments was making huge payments into a series of letterbox companies linked to the Guptas. We ran the names of these companies through our old records and discovered a ledger attached to an old set of court papers which laid out the exact percentages and which government deals these payments originated from. On the one hand I wanted to kick myself for not realizing the value of this barely legible photocopy sooner, but on the other it was really helpful in showing how an apparent kickback was channeled to the Guptas on a huge China Development Bank loan.”

Signal

“Generally, we try to stay away from normal phone lines. We’ve got a case going to the Constitutional Court, where we’ve been challenging the Regulation of Interception of Communications Act (RICA), which allows the state to spy on the communications of citizens. We’re challenging that on the basis that we know it has been abused in the past to spy on journalists. We have a judgment from a lower court confirming that aspects of RICA are unconstitutional, so we’re going to the Constitutional Court to get that confirmed, hopefully. So in the context of knowing that about RICA and knowing how compromised communications can be, we try to steer people towards more secure and encrypted apps.”

In April 2016, Susan Comrie flew to Dubai on an assignment to find the mansion the Guptas were alleged to have bought. (Screenshot: amaBhungane)

Metadata Search

“There are some amazing things you can do with coding and social media. But if you’re like me and ‘learn to code’ is on your eventual to-do list, there are also some great things you can do with very basic tools, like the Advanced Search tool on Twitter, and metadata tools like Make Adverbs Great Again, WayBack Machine, and WhoIs.

“For example, I was trying to track down the Guptas when they had fled to Dubai and I was sent over on what I thought would be a complete wild goose chase and a little bit daunting. Miraculously, someone actually gave me an address and I went to the house. There was no one there but there was a family crest which had been mounted on the outside and, bizarrely enough, it had a website address on the family crest.

“There were a lot of clues that said this was the Gupta house — including that it had the name Gupta in the crest — but we still weren’t entirely sure because it’s a common surname. My editor suggested that we look [up the website] on Who Is, and we found that it pointed back to the Guptas in South Africa and the Sahara computer company. That was useful because I tried to get property records in Dubai and they basically laughed me out of the office for asking if I could see who owned a house.”

Lynsey Chutel is a writer, journalist, and producer living in Johannesburg, South Africa. She has written and produced stories focused on gender, identity, development, and culture in Africa. Her reporting has appeared in AP, Quartz, The Guardian, and The New York Times as well as South African TV outlets.

Lynsey Chutel is a writer, journalist, and producer living in Johannesburg, South Africa. She has written and produced stories focused on gender, identity, development, and culture in Africa. Her reporting has appeared in AP, Quartz, The Guardian, and The New York Times as well as South African TV outlets.