Mexico Wages Cyber Warfare Against Journalists

For years, Citizen Lab has been sounding alarms about the abuse of commercial spyware. We have produced extensive evidence showing how surveillance technology, allegedly restricted to government agencies for criminal, terrorism and national security investigations, ends up being deployed against civil society.

For years, Citizen Lab has been sounding alarms about the abuse of commercial spyware. We have produced extensive evidence showing how surveillance technology, allegedly restricted to government agencies for criminal, terrorism and national security investigations, ends up being deployed against civil society.

Today’s report not only adds to the mountain of such evidence, it details perhaps the most flagrant and disturbing example of the abuse of commercial spyware we have yet encountered.

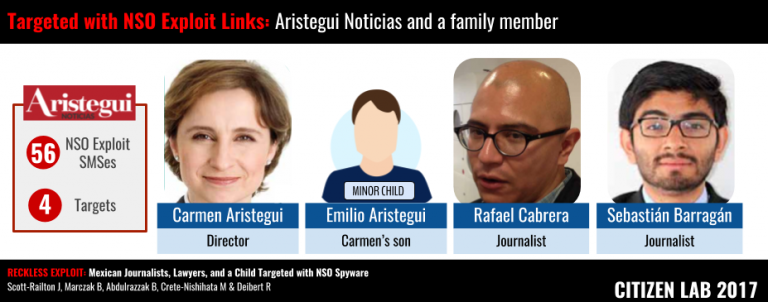

Working with Mexican civil society partners R3D, Social Tic, and Article 19, our team — led by John Scott Railton — identified more than 75 SMS messages sent to the phones of 12 individuals, most of whom are journalists, lawyers and human rights defenders. Ten are Mexican, one was a minor child at the time of targeting and one is a US citizen.

These SMS messages contained links to exploit the infrastructure of a secretive Israeli cyber warfare company, NSO Group. Had they been clicked on, the links would activate exploits of what were, at the time, undisclosed software vulnerabilities in the targets’ Android or iPhone devices. Known in NSO Group’s marketing as “Pegasus,” this exploit infrastructure allows operators to surreptitiously monitor every aspect of a target’s device: turn on the camera, capture ambient sounds, intercept or spoof emails and text messages, circumvent end-to-end encryption, and track movements.

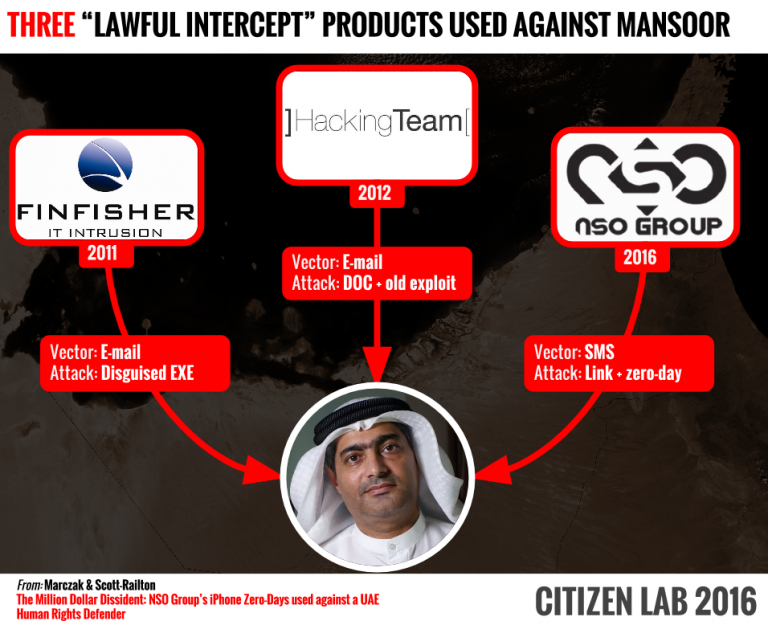

We first encountered NSO Group in August 2016 when UAE human rights defender Ahmed Mansoor shared with Citizen Lab researchers suspicious SMS messages he received containing links to NSO infrastructure. When we published our report on Mansoor, we had some evidence of targeting in Mexico that subsequently led to a follow-up report earlier this year on the use of NSO’s surveillance technology to target Mexican health advocates and food scientists.

The targeting we outline in our latest report, which runs from January 2015 to August 2016, involves a much wider campaign. It includes 12 individuals who share a common trait: investigations into Mexican government corruption, forced disappearances or other human rights abuses. All of the individuals who cooperated in our research consented to be named in the report. The August 2016 endpoint coincides with the time of our disclosure to Apple about NSO’s exploits, which led to the shutdown of NSO’s infrastructure (or at least that particular phase of it).

The targeting we outline in our latest report, which runs from January 2015 to August 2016, involves a much wider campaign. It includes 12 individuals who share a common trait: investigations into Mexican government corruption, forced disappearances or other human rights abuses. All of the individuals who cooperated in our research consented to be named in the report. The August 2016 endpoint coincides with the time of our disclosure to Apple about NSO’s exploits, which led to the shutdown of NSO’s infrastructure (or at least that particular phase of it).

Among the noteworthy aspects of this latest case are the persistent and brazen attempts by the operators to trick recipients into clicking on links. Each of the targets received a barrage of SMS messages that included crude sexual taunts, alleged pictures of inappropriate, threatening, or suspicious behavior and other ruses. Many received fake AMBER Alert notices about child abductions as well as fake communications from the US Embassy in Mexico.

What is most disturbing is that the minor child of one of the targets — Emilio Aristegui, son of journalist Carmen Aristegui — received at least 22 SMS messages from the operators while he was attending school in the United States. Presumably these attempts to infect Emilio’s phone were intended as a backdoor to his mother’s phone. But it is also possible the operators had a more sinister motivation. The attempts to infect both Carmen and Emilio took place at the same time Carmen Aristegui was investigating a major corruption scandal involving the president of Mexico.

Our report makes it clear that the NSO Group, like competitor companies Hacking Team and FinFisher, is unable or unwilling to control the abuse of its products. Time and again, companies like these, when presented with evidence of abuse, effectively pass the buck, claiming that they only sell to “government agencies” to use their products for criminal, counterintelligence or anti-terrorism purposes. The problem is that many of those government clients are corrupt and lack proper oversight; what constitutes a “crime” for officials and powerful elites can include any activity that challenges their position of power — especially investigative journalism.

Our report makes it clear that the NSO Group, like competitor companies Hacking Team and FinFisher, is unable or unwilling to control the abuse of its products. Time and again, companies like these, when presented with evidence of abuse, effectively pass the buck, claiming that they only sell to “government agencies” to use their products for criminal, counterintelligence or anti-terrorism purposes. The problem is that many of those government clients are corrupt and lack proper oversight; what constitutes a “crime” for officials and powerful elites can include any activity that challenges their position of power — especially investigative journalism.

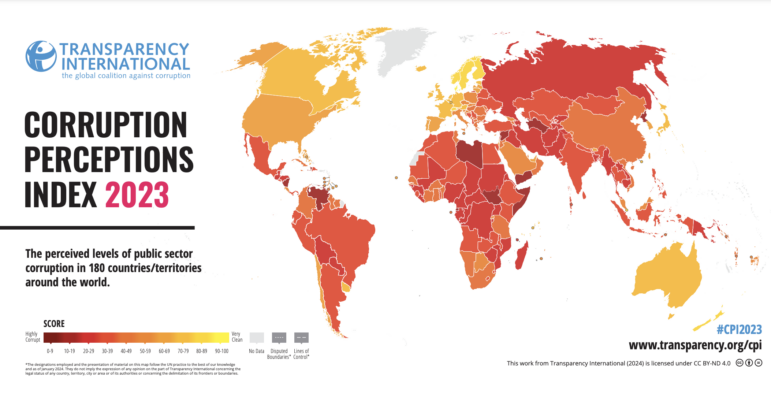

Mexico is a case in point. Ranked by the Economist’s Intelligence Unit as a “flawed democracy,” Mexico’s government agencies are riven with corruption. Mexico is one of the most dangerous places to be a journalist not only because of violence related to the drug cartels but also because of threats from government officials. As Reporters Without Borders notes, “[w]hen journalists cover subjects linked to organized crime or political corruption (especially at the local level), they immediately become targets and are often executed in cold blood.”

In spite of these glaring insecurity and accountability issues, the NSO Group went ahead and sold its products to multiple Mexican government agencies, according to leaked documents reported on in the New York Times. Other leaked documents show that Mexico was at one time another commercial spyware company’s (Hacking Team) largest single country client. Should it come as any surprise that these powerful surveillance technologies would end up being deployed against those who aim to expose corrupt Mexican officials?

What is to be done about these abuses? In a recent publication, Citizen Lab senior researcher Sarah McKune and I outlined a “checklist of measures” that could be taken to hold the commercial spyware market accountable, including application of relevant criminal law. It is noteworthy in this regard that while in the United States, the minor child Emilio Arestigui received SMS messages purporting to be from the US Embassy. Impersonating the US government is a violation of the US Criminal Code, and the targeting may very well constitute a violation of the US Wiretap Act. At the very least, it is a violation of diplomatic norms. How will the United States Government respond?

NSO Group is an Israeli company and thus subject to Israeli law. In the past, Israel has prided itself on strict export controls around commercial surveillance technology. Yet this latest example shows yet again the ineffectiveness of those controls. Will Israeli lawmakers tighten regulations around NSO Group in response?

Among the checklist of measures McKune and I identified is the importance of evidence-based research on the commercial spyware market to help track abuses and raise awareness. It is important to underline that the work undertaken in this report could not have been done without the close collaboration between Citizen Lab researchers and Mexican civil society groups, R3D, SocialTic and Article 19.

Collaborations like these are essential to exposing the negative externalities of the commercial spyware market, documenting its harms, and shedding light on abuse.

I suspect it will not be the last collaboration of this sort.

Read the full report, “Reckless Exploit: Journalists, Lawyers, Children Targeted in Mexico with NSO Spyware,” authored by John Scott-Railton, Bill Marczak, Bahr Abdulrazzak, Masashi Crete-Nishihata, and Ron Deibert.

This post was originally posted on Ron Deibert’s blog and is cross posted here with permission.

Ron Deibert is a professor of political science and the director of the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto. He is a founder and former principal investigator of the OpenNet Initiative (2003-2014) and a founder of Psiphon, a world leader in providing open internet access. Along with numerous books and articles on internet censorship, surveillance and cyber security, he is author of Black Code: Surveillance, Privacy and the Dark Side of the Internet (Random House, 2013).

Ron Deibert is a professor of political science and the director of the Citizen Lab at the Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto. He is a founder and former principal investigator of the OpenNet Initiative (2003-2014) and a founder of Psiphon, a world leader in providing open internet access. Along with numerous books and articles on internet censorship, surveillance and cyber security, he is author of Black Code: Surveillance, Privacy and the Dark Side of the Internet (Random House, 2013).