The Spanish data journalism site Civio was founded on the principle of opening up data to the public, using freedom of information requests and other sources to uncover what was happening in the country. Image: Civio team, courtesy of CIVIO

Civio: Data Journalism Pioneer in Spain, Still Pushing For Greater Transparency

It was July 8, 2025 when journalists from the Spanish data journalism organization Civio went to the Supreme Court in Madrid for a hearing to fight for transparency. The cause? A years-long project to investigate how an algorithm used by the government decides who is eligible for low-income electricity payment works — and to understand why it sometimes fails.

The team at Civio has been trying for years to get the authorities to share the source code behind the algorithm, but unsuccessfully.

The court is still deliberating, and the outlet expects a decision imminently. If they win the case, they believe it will establish a new transparency standard in Spain.

“Whatever happens, our commitment is unwavering,” the team wrote in a recent newsletter. “We will continue to report and monitor public algorithms and demand accountability, because we know that what you can’t see, you can’t control.”

This case, known as BOSCO because of the Spanish term for the payment is “bono social,” is one out of eight court-cases Civio has been involved in in recent years, all of the same nature and with the same goal — to open up data to the public.

This crusade for transparency was part of the initial idea behind Civio, which was founded by David Cabo, a software engineer and open data expert, and Jacobo Elosua, an entrepreneur with a banking and investment background, back in 2012.

Cabo had been living in the UK, where that country’s freedom of information laws had been working “very well, so I wanted to do something like that,” he tells GIJN. “At that time, Spain was one of the few countries in Europe that didn’t have an access to information law.”

Just two years after Civio was founded, in 2014, Spain enacted the Law on Transparency, and one of Civio’s first battles had been won.

Although the passing of the law was a cause of celebration, it soon became clear that opening up data alone was not enough.

“Initially, they believed that opening up data… would have some impact,” explains Eva Belmonte, Civio’s co-director, who spent nearly a decade working for El Mundo before joining the team. “Over time, they realized that publishing data wasn’t enough. Data needed to tell a story.”

Marrying Cabo’s passion for data with Belmonte’s experience as a reporter brought them new avenues — and ever-growing reach.

As Cabo explains: “We made a great team working together on investigations, because when I saw data, I could sense what could be interesting for a journalist, and Eva, being a journalist, was also able to understand a little of what was technically possible. It’s important that journalism and the technical side talk to each other and that each understands the needs or possibilities of the other to design an investigation together.”

With mutual understanding, they began pushing the boundaries to become an impactful player in the Spanish media landscape. Civio, which was registered as a Madrid-based nonprofit, has been a pioneer of data journalism in Spain, handling long-term data-based investigations with real impact.

Nowadays, they have 10 staff members, a network of collaborators, and more than 2,000 associates that help fund their work through an annual or monthly subscription. And there has been recognition, too, with national and international awards to their name, such as the Gabriel García Márquez Prize, the Premio Rey de España, and Sigma Awards for data journalism. CIVIO joined GIJN not long after its founding in 2012, and is a member of the European Data Journalism Network (EDJNet).

Data as Public Interest Tool

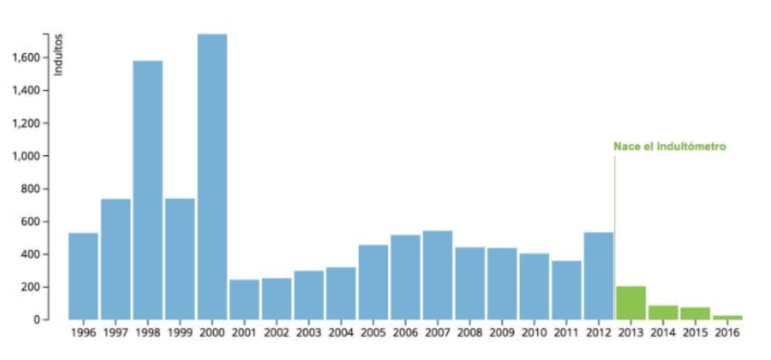

A graph showing the number of pardons granted in Spain by year. After the investigation was published, the numbers dropped dramatically — see the years in green. The interactive tool let users search for pardons granted according to the type of crime, compare annual data, and evaluate how different governments made use of this privilege. Image: Screenshot, Civio

One of their iconic and most impactful investigations was an early one — The Pardonometer, or El Indultómetro in Spanish — which dug into how pardons were being used in the justice system and how “forgiveness has evolved over time.” The team extracted information from the Official State Gazette (BOE), analyzed it, visualized it, and revealed how the system works and how, in some cases, pardons were being misused.

“Previously, pardons were only discussed when there was a controversial one. But we compiled all the data: how many pardons, what crimes, how long it takes, who is pardoned,” Belmonte explains. “It was the first time context was put into it and that had a huge impact: the number of pardons suddenly dropped, because suddenly it became clear that it wasn’t an exceptional event, but an everyday occurrence.”

Belmonte had started digging into the data hidden with the BOE before joining Civio, and finding interesting stories in it. “BOE seemed to me like a treasure trove for journalism that no one was reviewing,” she says.

Although Civio works on long-term projects, some of them lasting for a number of years, they still keep an eye on the Official Gazette, keeping it as one of their special beats.

Another thing that distinguishes Civio from a traditional newsroom is their focus. “We’re focused on the public sector: on everything related to the public sector, and not from a general critical perspective, like ‘the public sector is bad,’ but the other way around,” Belmonte explains. “We believe that we must take care of the public sector, and to take care of it, we must monitor it: that public resources are used well, that healthcare works, that there is no corruption.”

They spend a lot of time becoming experts on a certain topic and only then start to publish. Projects have focused on health, the environment, public spending, technology, public contracts, and on secret governmental advisors, a topic for which they have been struggling to get data for years. Along with Pardonometer, projects like Where Do my Taxes Go? (¿Dónde van mis impuestos?) and Spain on Fire (España en llamas) also had a huge impact. Spain on Fire was the first database offering data in context to show what was happening with the forest fires ripping through parts of the country: where they were happening, when, how many, and how often.

“We don’t use data to corroborate a theory, but to understand what’s happening in a given area, without preconceived notions,” Belmonte says. In general, Civio’s impact has been in making public information accessible and understandable. “Information that was widely discussed, but without context or analysis,” she added. And their guiding light throughout all these projects? “Let the data speak.”

Grappling with Data

Journalists from Civio usually ask for data using FOIA, but that can become part of the struggle, with some requests for information leading to multiple court cases and years-long processes. Sometimes, the team notes, there isn’t a single source for data so they have to build everything from scratch.

One example was when Cabo programmed a robot to call every 30 minutes the helpline for people needing assistance with the minimum living income support payment — the ingreso mínimo vital. For 17 days, no one answered. “Social measures are useless if they do not reach those who need them most,” the team wrote, following that investigation.

“If you pose an unanswered question and build a foundation for answering it, the approach changes completely and has much more value. It’s a different level. It’s more fun, too,” says Belmonte.

And even when they get the data, it’s not always plain sailing: sometimes the format is unusable, or different regions in the country collect data in different ways so they spend weeks cleaning it and looking for a way to use it.

In recent newsletters, Adrián Maqueda, a data journalist in charge of analysis and visualization at Civio, has set out the challenge of updating the databases they have when the authorities change the methodology and way of collecting data.

For data analysis and visualizations, they use programming languages such as R, Python, and Javascript.

“The good thing here is that each visualization is created with a specific topic in mind. We can reuse parts of the code or certain elements, but each visualization is created from scratch based on the information we have — everything is super personalized, super specific, new, and handcrafted,” said Maqueda.

This personalized approach can be seen not only in the way of doing work, but also in their relation with readers and supporters.

Keeping your Readers Close

Civio started developing its associates program in 2017, with the idea that it could become a more significant source of funding and that there could be benefits to having readers directly financing their journalism. Today, around 35-40% of their budget — which is published annually, true to their campaign for openness — comes from this program, another 40-45% from private funding sites like European AI Fund, Civitates, and Limelight. The rest comes from European projects.

“We started by holding annual meetings with our supporters in the office at Christmas, first with 20 people, then 50, then growing. People knew our office, our refrigerator, the bathroom, knew where we worked, and we could get to know each other,” remembers Javier de Vega, journalist and communication officer at Civio, and a team member from the very beginning. “That’s a very nice thing, and although it’s harder to maintain that close relationship as we grow, we still try to maintain it.”

Civio has been recognized as an organization that always goes one step further, developing multiple tools to help readers navigate their way through complex legislation, creating video games, and being very transparent with their methodology and data.

“For example, when we investigate public contracts we make that database available to organizations that monitor corruption or we create an interactive video game to explain how difficult it is to obtain European citizenship, with engaging and easy-to-understand information,” de Vega explains.

When they were doing the investigation on the social bonus story, they created an app so people can easily find out if they are eligible for this support. It took three months to understand the regulations, but the impact and usefulness was clear: it has been used more than 1.5 million times since 2019. That “usefulness” is something they are very proud of — but it is also valued by their associates and builds trust.

“With the minimum living income or the social bonus tools, we make an extra effort to reach vulnerable people who truly need help. We contact more than 250 NGOs, social services, and associations that use our tools to directly help people,” de Vega explains. “One NGO set up a call center to help people apply for the social bonus using our app, helping 17,000 people.”

Democracies Also Struggle with Open Data and Media Trust

While Spain ranked relatively highly on the 2025 Reporters Without Borders (RSF) Global Press Freedom Index — 23rd place, out of 180 — both RSF and the team at Civio think there is room for improvement.

RSF notes that press freedom is “threatened by an increase in abusive lawsuits (SLAPPs) and the political targeting of journalists,” while Civio suggests the government can be slow to collaborate or respond.

“You have to fight for every piece of information, and when you do get the data, it’s bad. Sometimes even the judges are ignored,” Belmonte explains. “These processes take a long time: the transparency process can take a year, and then the trial, four more, so when the information arrives, it doesn’t matter anymore — we do it more to set a precedent than for the content itself.”

Eduardo Suárez, the head of editorial at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, and a former reporter for Spanish newspaper El Mundo, said that despite Spain’s transparency law, the government sometimes acts “as if the law didn’t exist.”

That, he said, makes Civio important in the media ecosystem.

“Civio stands out for the quality of its work, with a focus on investigative journalism, promoting transparency in government, and holding power to account,” he says. “They are a rare organization in Spain, where so many outlets are hyper-partisan. Their work is thorough and crucial for democracy and they punch way above their weight.”

Ana Ćurić is a freelance investigative and data journalist from Serbia, based in Spain. She has worked with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, Investigate Europe, and OCCRP, and her work has been shortlisted for both national and international investigative journalism awards. She holds a Master’s degree in Advanced Journalism and is currently completing a PhD in Communication at Blanquerna – Universidad Ramon Llull in Barcelona.

Ana Ćurić is a freelance investigative and data journalist from Serbia, based in Spain. She has worked with the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, Investigate Europe, and OCCRP, and her work has been shortlisted for both national and international investigative journalism awards. She holds a Master’s degree in Advanced Journalism and is currently completing a PhD in Communication at Blanquerna – Universidad Ramon Llull in Barcelona.