Investigative News Startups Talk Membership Models

Many people don’t trust media giants. That’s what we’ve been hearing in the past two months of interviews with a wide variety of European publishers with membership models. These upstart publishers represent different newsroom and audience sizes, focus areas and geographies. Yet they’re hearing similar complaints around information believability across the audiences they serve.

When a country’s most prominent media organizations have foreign backers, that frequently raises questions. Belgian publishing house De Persgroep controls the largest chunk of the market in Holland, and publishers like Rheinische Post Mediengruppe from Germany and Ringier Axel Springer Media from Switzerland have outsized influence in the Czech Republic, Serbia, Poland and Slovakia.

When a country’s most prominent media organizations have foreign backers, that frequently raises questions. Belgian publishing house De Persgroep controls the largest chunk of the market in Holland, and publishers like Rheinische Post Mediengruppe from Germany and Ringier Axel Springer Media from Switzerland have outsized influence in the Czech Republic, Serbia, Poland and Slovakia.

The funding crisis that hit traditional media a decade ago continues to wreak havoc on companies’ revenues. It has forced major media houses to stabilize earnings by selling less profitable outlets to local publishers, sometimes to oligarchs who intend to control the distribution of information. Examples include Rheinische Post Mediengruppe selling Czech media company Mafra to billionaire Andrej Babiš in 2013 and Slovakian Petit Press to oligarch group Penta in 2014.

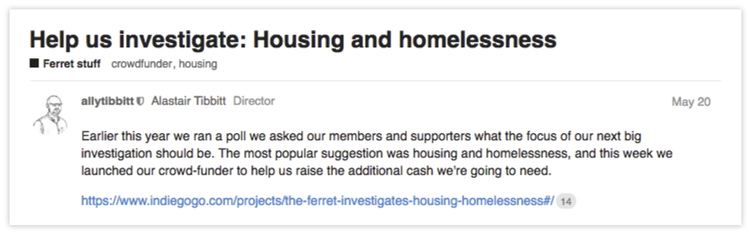

This has prompted some journalists to forfeit their roles with regional and national publications and establish new groups like Dennik N and Direkt36 in the hopes of regaining editorial independence. The editors of European organizations with membership models report on topics ranging from national issues (like The Ferret’s audience-funded investigation into housing and homelessness in Scotland) to those of major international importance (such as Correct!v’s look at the MH17’s crash over eastern Ukraine). (You can read more about our research approach and other project interviewees here.) We welcome you to compare our findings with practices and plans in your own newsrooms.

This has prompted some journalists to forfeit their roles with regional and national publications and establish new groups like Dennik N and Direkt36 in the hopes of regaining editorial independence. The editors of European organizations with membership models report on topics ranging from national issues (like The Ferret’s audience-funded investigation into housing and homelessness in Scotland) to those of major international importance (such as Correct!v’s look at the MH17’s crash over eastern Ukraine). (You can read more about our research approach and other project interviewees here.) We welcome you to compare our findings with practices and plans in your own newsrooms.

1. Members can support stories that otherwise wouldn’t get told by contributing ideas, fact checking and co-reporting.

Arne van der Wal, cofounder of Follow the Money, a Dutch investigative outlet focusing on finance, said: “People think that legacy media have a blind eye for important problems. It’s more like ‘what important people say’ rather than real investigative work.” His site invests broader contributions from their members into hardcore financial investigations in the Netherlands. Editors often append articles after they see a high amount of reader discussion in comments.

Beyond general reader commentary, Follow the Money’s reporting benefits from professionals who share relevant expertise in the comments to improve others’ understanding of the story. Top comments are highlighted on the front page of the website, something that is rarely seen on most publishers’ sites in the interest of squeezing in more homepage stories.

Reader’s comment: “It’s undoubtedly healthy to eat a lot of fresh fish, but is that the reason to give people on higher incomes subsidy on their cod purchases?”

The Ferret uses a similar approach in its reader-supported reporting in Scotland. Reporters and editors commonly discuss investigation ideas publicly with their readers before undertaking their research and writing.

Peter Geoghegan, director of The Ferret, said, “When we did a story about homeless and housing, we put that on the forum and asked people for help.” Their last investigations into fracking and refugees got thousands of shares on social media because the whole process was transparent for members and contributors felt as they made a difference. Those stories got mentioned in public policy documents, and in both UK and Scottish parliaments.

Help Us Investigate: On its forums, The Ferret’s staff asked members for investigation-specific contributions, a practice that The Guardian also uses for some reporting projects.

Inside Story in Athens, Greece, publishes articles and hosts events that start with subscribers’ pitches. One of their readers wondered why Greek agricultural products fail to stand out in the international market and pitched it as an investigation idea during the #YourStory event. All stories were submitted via email, so the editorial committee could select six finalists. They were invited to Inside Story’s office to prepare short presentations for the event where members could vote for the top three topics to be investigated. Editor Machie Tratsa, who specializes in environmental issues, conducted additional research and reporting on the agricultural story. After it was published, member Evangelos Gerasimou commented on the piece: “With this story, my money [to support Inside Story] was worth it.”

2. It’s difficult but it’s possible to raise supplementary funding.

Dennik N in Bratislava, Slovakia, uses member-provided funds for international reporting efforts, which have been among the most visited articles on the site. Dennik N ran a story about the Japanese population getting older and lessons Slovaks can learn from that by 2060. Still, cofounder Tomas Bella says that raising just €2,000 for a trip was exhausting: “You have to spend a lot of time on communication with backers.”

Asking readers for help and receiving a good initial response might sound like a win. But publishers beware: the coordination costs that come with user participation can be larger than the ultimate benefits gained. (You can find more on the topic of the true cost of audience member fundraising and planning considerations in one of our earlier posts.)

Asking readers for help and receiving a good initial response might sound like a win. But publishers beware: the coordination costs that come with user participation can be larger than the ultimate benefits gained. (You can find more on the topic of the true cost of audience member fundraising and planning considerations in one of our earlier posts.)

Dennik N now plans to crowdfund a larger amount to pay for a full-time foreign correspondent. As Bella explained, “This is a way to check whether readers really want us to have that or not. We also have private Facebook groups for subscribers only where readers can complain, comment or pitch their own stories.”

Correct!v from Essen, Germany, raises funds for freelance journalists’ reporting. Luise Lange, community engagement editor, explained: “You have to connect with Correct!v and talk about the topic first, but if it fits our editorial strategy you can raise money and do co-reporting [with members].” Correct!v encourages other media companies to share their content for free as they function as a nonprofit investigative newsroom and measure their success through societal impact.

The site proclaims that the more people who read their work, the better: “It doesn’t matter if you are a local blog, an online-platform, a newspaper or a radio station. Please, help yourself, for free.” Their research on 71,000 doctors in Germany who received millions of euros from the pharmaceutical industry is similar to ProPublica’s well-known project Dollars for Docs.

Steal Our Story: Correct!v’s note for publishers encourages media to share their investigative work.

3. Media sites with membership are better able to function than their competitors in difficult scenarios.

One of the strengths of member-funded media is that these sites can function even while (and perhaps especially well) legacy media in their countries are in serious institutional crises. A media crisis hit Hungary in 2010 when a new government of the prime minister Viktor Orbán took power. Public media stations were immediately taken over by officials who were antagonistic to a free press and converted to broadcasters for politicians’ messages.

In 2016 the largest Hungarian opposition daily newspaper was shuttered and its owner Mediaworks sold to an ally of Viktor Orbán. Andras Petho, a reporter for 15 years, co-founded Direkt36 as an investigative non-profit so the Hungarian government wouldn’t be able to influence it. His outlet has investigated corruption among Hungarian politicians, was shortlisted for the European Press Prize and was the only Hungarian partner in the Panama Papers project.

We can see parallels here with the Russian media company RBC, which was sold to an oligarch this June and omitted sharing information about a secret torture prison near Moscow. This is hugely notable for an organization that was commonly regarded as one of the most reliable investigative newsrooms in the country before it was sold.

Reporter turned freelancer Ilya Rozhdestvensky left his job at RBC to push the investigation further. To publish it he turned to Republic, which launched in 2009 with private funding and a focus on longform and opinion pieces about economics, business and politics. Rozhdestvensky wrote that Republic, which now has 24,000 paying subscribers, according to publisher Maxim Kashulinsky, helped him edit the piece. The collaboration reminded him “how such a job should be done and what questions should be asked about the piece” editorially.

4. Investigative outlets can serve as sources of desirable knowledge and skills for members.

We’ve been pleasantly surprised by the number of creative, highly productive interactions we’ve seen between some publishers and their readers. These investigative media organizations don’t focus only on producing and publishing stories. They’re invested in teaching their members skills that might help in investigations as well as members’ own professional development.

Training: The Bristol Cable in Bristol, England, runs free workshops to teach its members how to interview, edit video and conduct investigative reporting. They have also developed a five month program for training in journalism, which is open to anyone. There is an application process, but they don’t expect people to have any experience. With trainers from The Guardian, the Centre for Investigative Journalism, and The Bristol Cable, students are trained with the purpose of being ready to “take on dodgy businesses, challenge government, interview a range of people and do high quality research,” according to the site.

Training: The Bristol Cable in Bristol, England, runs free workshops to teach its members how to interview, edit video and conduct investigative reporting. They have also developed a five month program for training in journalism, which is open to anyone. There is an application process, but they don’t expect people to have any experience. With trainers from The Guardian, the Centre for Investigative Journalism, and The Bristol Cable, students are trained with the purpose of being ready to “take on dodgy businesses, challenge government, interview a range of people and do high quality research,” according to the site.

Meeting IRL: Republic runs member meetups weekly in Russia. Members attend informal “update” sessions there they can learn what’s happening in artificial intelligence, crypto economies and virtual reality through lectures by industry professionals. These talks are also featured as articles on the site. Republic also runs “Ask Me Anything”-style events with relevant experts who present on topics of interest to their fellow members, including education, private finance and healthcare.

Collaborative fact checking: The Ferret hosts monthly story fact-checking events in which 20 to 30 members participate. Geoghegan said it’s important to bring value or give people skills so they will want to come back. During fact-checking workshops members learn to find information, check sources and verify authenticity. Non-members can also participate for £5, which comes with a three month subscription to The Ferret. Workshops last for three hours and are held in different locations, with the most recent one taking place in a local church. These events have been so successful that they are considering offering a “fact-checking roadshow” across Scotland. The Ferret received €50,000 in funding from the Google Digital News Initiative to more broadly develop this approach following Brexit.

Collaborative fact checking: The Ferret hosts monthly story fact-checking events in which 20 to 30 members participate. Geoghegan said it’s important to bring value or give people skills so they will want to come back. During fact-checking workshops members learn to find information, check sources and verify authenticity. Non-members can also participate for £5, which comes with a three month subscription to The Ferret. Workshops last for three hours and are held in different locations, with the most recent one taking place in a local church. These events have been so successful that they are considering offering a “fact-checking roadshow” across Scotland. The Ferret received €50,000 in funding from the Google Digital News Initiative to more broadly develop this approach following Brexit.

Student education: Similar to the News Literacy Project in U.S. cities, the staff at Dennik N tour Slovakian middle schools and offer student workshops on recognizing fake news. They also print magazines for teachers who may lack textbooks but are eager to teach critical thinking and news judgement to children. The publication crowdfunded €30,000 for a book donation program which is intended to help parents and teachers explain risks that young people face on the web. Per the site, its materials offer “specific examples of hoaxes and manipulations that spread among Slovak Facebook and help shape their worldview.”

These are promising answers to a core question about membership viability in our research: What member participation activities are most useful to news sites and rewarding to members? “And” may be the most important word here as we look to understand positive examples of news sites and loyal members both being satisfied with the exchange. We’re eager to learn about other examples that you’ve found — please share them on Twitter.

This post originally appeared on the Membership Puzzle Project website and is reproduced here with permission. Presenters from the Membership Puzzle Project will speak at the 2017 Global Investigative Journalism Conference.

Andrew Urodov is a research assistant at the Membership Puzzle Project, a project to develop research and knowledge on member-supported, sustainable strategies for public service journalism. Andrew also contributes to The Outline, Republic, The Calvert Journal, OpenDemocracy and Esquire Russia.

Andrew Urodov is a research assistant at the Membership Puzzle Project, a project to develop research and knowledge on member-supported, sustainable strategies for public service journalism. Andrew also contributes to The Outline, Republic, The Calvert Journal, OpenDemocracy and Esquire Russia.