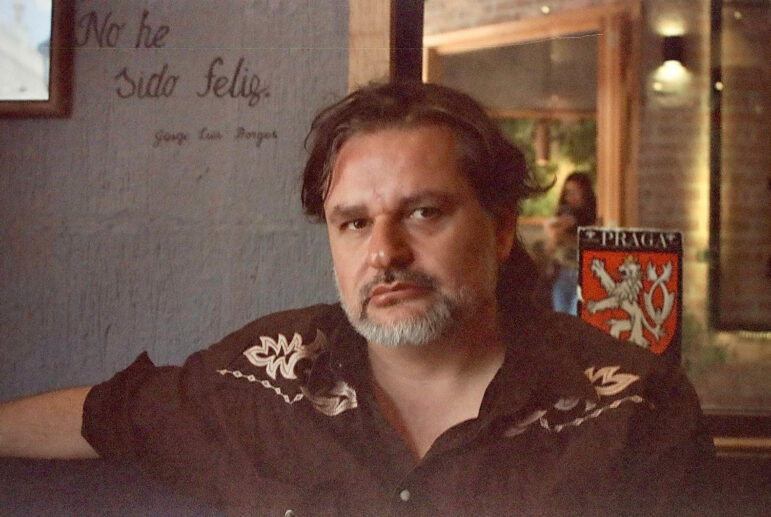

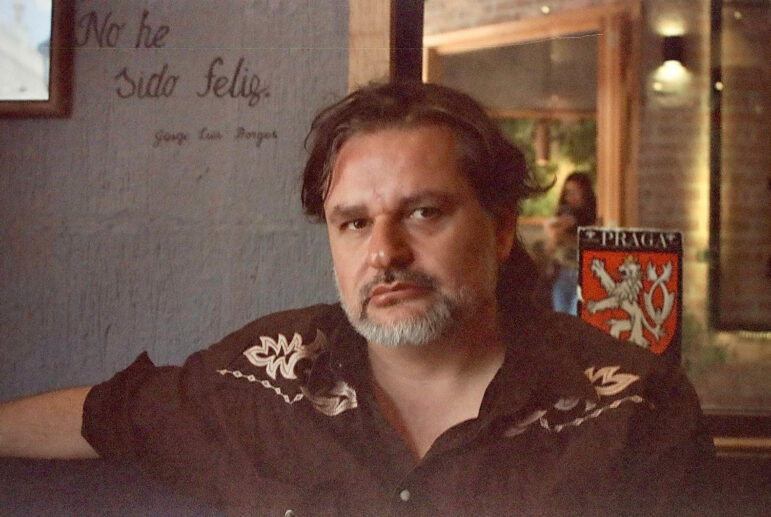

The reporter, author, and filmmaker has said investigating the mafia feels like working in a "world of shadows where everything is not necessarily what it seems." Image: Courtesy of Diego Enrique Osorno

Investigating Mexico: An Interview with the Reporter, Writer, and Film-Maker Diego Enrique Osorno

Read this article in

People who know Diego Enrique Osorno will tell you he never stops. A boat journey across the Atlantic arrives on the heels of an interview with a drug lord; a month covering the drugs war prefaces a further seven investigating a deadly blaze in a daycare centre; a documentary on the disappearance of a poet is followed by a series on the murder of a presidential candidate; a deaf-mute migrant is as worthy of a biography as one of the richest men in the world.

Osorno never stops. He has written a dozen books, written or directed numerous documentaries, and worked on countless investigations to tell the stories of Mexico and the city of Monterrey, where he was born.

An award-winning reporter, he manages to chronicle the violence of the drug war and the worst impulses of the government, but also dissidence, talent, and bravery. He garners unprecedented access, meaning his reportage is capable of encompassing the powerful and the victims, with all the nuances in between.

His most recent book, “En la montaña” (“On the Mountain”), was the winner of the 2023 Anagrama Prize in the long-form and narrative feature writing category. He spoke to GIJN while filming his latest project.

GIJN: You met the poet Samuel Noyola in 1999, and 20 years later made a documentary about his disappearance. You followed the Zapatista movement from an early age, and now it informs your most recent book. Are there themes you can’t leave behind?

Diego Enrique Osorno: I lived my adolescence and youth in the 1990s, in a decade in which Mexico and the world went through an economic, social, and political transformation after the end of the Cold War. In that time of my life, and during that moment in the country, I was faced with a lot of conflicts, dilemmas, choices, and ghosts. I’ve dedicated my time to trying to understand the present, because I’m a journalist, and we work with current events, but I have constantly kept as a compass, or as a reference for present dilemmas, those that manifested in that early decade.

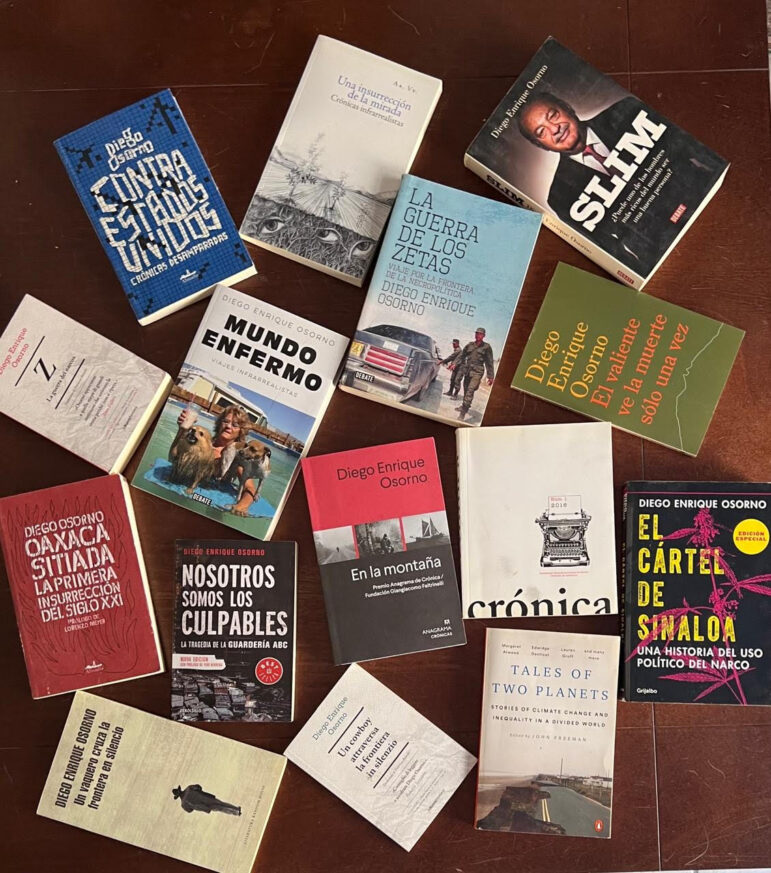

Osorno has written books about the Sinaloa and Zeta cartels, a wealthy landowner who stood up to the cartels trying to force him from his property, and about Mexico’s wealthiest person, Carlos Slim, among other topics. Image: Courtesy of Diego Enrique Osorno

GIJN: Over time, you’ve employed different tools to cover these stories. There is the early passion for poetry, learning the craft of the ‘crónica’ or long form narrative, and your ample work in documentary filmmaking. How have you chosen each way of narrating?

DEO: I think I am a frustrated poet, and that journalism has allowed me to keep some sanity and have a land to plow, a space to try to explore. I am particularly interested in investigative journalism, and above all in the ‘crónica,’ which for me is the possibility of delving not only into the facts, into the events, but also the meaning and the transcendence of those facts. What interests me, and what I believe feature writing always requires, is to move from investigation to immersion. I try to listen a lot and observe a lot before I speak and write. I also like the ‘crónica’ in its audiovisual format, which for me is the documentary. The audiovisual world has another grammar, that of the image, and for me, it is a dialogue, an exploration inspired by things from reality that matter to me, that hurt me, and that move me.

GIJN: Your interviews portray characters at opposite extremes of society, from the story of your uncle Gerónimo González Garza, a deaf-mute migrant, to that of Carlos Slim, Mexico’s richest man. What do you look for in these portraits? How do you choose them?

DEO: There is always some manner of mirroring effect with these subjects, especially when I do profiles or biographies. In the case of my uncle, it meant telling the story of someone who taught me about the countryside, about the land, and who, in a certain way, made me reconcile with northeastern Mexico. I am from Monterrey, a city in the north of the country that has a Texan culture. We are like wild Texans. That culture has always created a conflict in me, but when I wrote the story of my uncle, I understood many of the things about that culture in which I grew up. Deny it as I may, most of my work has to do with Monterrey. I made that documentary about Samuel Noyola, perhaps the most important poet from Monterrey; I have a story about a rancher named Alejo Garza Tamez, who defended his property in the middle of the drug war, and several chapters of my books about the Zetas and Sinaloa cartels. Just as I return to the 1990s, I also return to northeastern Mexico. That is what my uncle’s story gave me.

In the case of Carlos Slim, I began to work on his biography after covering the 2006 uprising of the Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca against the state government. That same year I also witnessed the brutal repression in San Salvador Atenco by federal, state, and municipal forces, where the police raped many women. I also followed the miners’ crisis in Pasta de Conchos [where 65 miners died], as well as the protests in Lázaro Cárdenas, in Fresnillo, in Cananea.

The year 2006 was one of great upheaval, and that triggered a reflection about how it was possible that in this country that I was seeing, that I was living in, that I was narrating, there also existed the world’s richest man. It was right then, in 2007, that Slim was considered by Forbes, for the first time, the richest man in the world. That clash cut deep for me, and I realized that there was very little information about him. The biography started from that confrontation. I always attempt to juxtapose personalities, ideas, and positions. In the process, I also realized that Latin American journalism, which is very vigorous in portraying injustice and unequal societies, rarely succeeds in gaining access to the elites. That was my starting point with Slim.

GIJN: You have said that when interviewing difficult-to-access figures, like the drug lord Mayo Zambada, reporters have to immerse themselves. Can you tell us about that process?

DEO: To have that immersion, you have to introduce yourself and explain who you are and what you are expecting from that encounter. That is something I always do in all my interactions. When I approach someone, I tell them: I came to you because this happened, I have this concern, and I want to understand this. I am forthright about my issues with them, and I try to do it respectfully, even when they are someone I have a very critical view of. I have interviewed murderers, people who have made others disappear, who enrage me. Even so, if that person is willing to offer up something about their experience that is meaningful to me, then I have to be respectful, not with their version of the facts, but at least during the encounter.

In extreme cases, as in my conversation with Mayo Zambada, it was not only a matter of establishing a common ground and achieving that immersion I sought, it was also a matter of security. All my communication before that in-person meeting had been through other people. It is a mafia world, a world of shadows, where everything is not necessarily what it seems. It felt very important to me that when Zambada and I met, he would hear firsthand who I was beyond what he had been told. To tell him I was not there for money and had no agenda other than to understand. To establish a conversational relationship on that basis, not just objectifying the person, but between two subjects who are talking. One subject wants to understand something, and the other party can help them do so.

GIJN: You have portrayed the social movements and tragedies of the last decades in Mexico, as well as different facets of the drug war. How do you individualise each story, with the pain and complexity each brings?

DEO: The journalism that I try to do is one that not only investigates but also immerses. Let’s take the case of the ABC daycare center. The fire occurred on Friday, June 5. I arrived the next day. The number of children who had died was not yet known; there was talk of five or ten. The government was already trying to conceal what had happened, and I realized that there was something else going on. I remember that on Monday, when the official death toll was acknowledged [more than 49 children died, and a hundred were injured], media from all over the world arrived for this almost biblical tragedy. The newspaper I worked for told me I had to go to the children’s funerals to film and talk to the parents. I flatly refused: What could I add about the pain that the death of a child causes, in a fire?

Instead, I began to investigate a document in which the names of some officials appeared as owners of the daycare center. It was the result of a process of outsourcing that the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS) had irresponsibly carried out in a very disguised way… I focused on that and didn’t do any stories with the mothers and fathers.

I spent months researching and documenting what had happened, but always from the viewpoint of corruption. That caused the fire for me, not the failure of an air conditioner. It was seven months later that one parent — Roberto — said to me over coffee, “Hey, why haven’t you ever asked me my story? And I told him: “Because I am here to listen, to me, the important thing is to denounce corruption, to make visible the demands that you have.” “I want to tell you my story,” he said. And he did it because I had been there.

When that immersion happens, it’s because you’ve been there for a long time, you’ve had the ability to listen, and you’ve had patience. The world nowadays has no patience for anything; everybody wants things fast and immediately. But patience achieves immersion. It may not allow you to understand — I will never understand the tragedy of losing a child to a fire caused by corruption — but it will allow you to take the human pulse of a tragic, historical, and public event, and its humanity. And that humanity is what I think is important to convey in my stories.

Diego Courchay is an associate editor at The Delacorte Review and a GIJN collaborator. He previously worked as a news producer for NBC TELEMUNDO, and as a reporter for Agencia EFE, Nexos, and Proceso magazine. He is a graduate of Columbia University in New York, and writes and reports in English, Spanish, and French.

Diego Courchay is an associate editor at The Delacorte Review and a GIJN collaborator. He previously worked as a news producer for NBC TELEMUNDO, and as a reporter for Agencia EFE, Nexos, and Proceso magazine. He is a graduate of Columbia University in New York, and writes and reports in English, Spanish, and French.