Manaus , AM 10/07/2021 - Ka´tia Brasil e Elaíze Farias fundadoras da Agência Amazônia Real durante filmagens do documentário para a Abraji no Bosque da Ciência do INPA (foto: Alberto César Araújo/Amazônia Real)

Investigating Illegal Gold Mining in the Amazon

Read this article in

The scars left behind from illegal gold mining within the Yanomami Indigenous territory. Image: Bruno Kelly/Amazônia Real

In Brazil’s northernmost region, the land of the Yanomami Indigenous people was once a natural paradise. But since the 1970s, this area within the Amazon biome has attracted a surge of outsiders in search of gold — and the results have been devastating.

Covering almost 10 million hectares in the states of Roraima and Amazonas, the Yanomami Indigenous Territory (TI, in Portuguese), is the largest Indigenous area in Brazil, measuring twice the size of Switzerland. It is estimated that 38,000 Yanomami people currently live there and in an adjacent Indigenous territory across the border in Venezuela, where at least one group lives in voluntary isolation from the world outside.

As a community made up of small-scale farmers, hunters, and gatherers, the Yanomami believe that the forest is a living entity with complex cosmological dynamics — an entity now under threat by the unbridled greed of outsiders. Currently, mining on Indigenous land in Brazil is not allowed: so any gold extracted from these regions is classified as illegally taken, and when traded on, illegally sold.

In the 1990’s when investigative journalist Kátia Brasil lived in Roraima, she used to visit the Yanomami land regularly. “At that time, I saw this territory intact, with a lush native forest full of biodiversity,” Brasil told GIJN.

Since then she has witnessed a dramatic change. “Today, when we look at the Yanomami territory, we only see holes – scars of the destruction caused by this illegal trade in gold that involves people from various fields,” she explains. This mining also has other, possibly fatal repercussions. Recently, two Yanomami children drowned in a river near where illegal gold miners were operating and while authorities are still investigating the incident, a local Indigenous leader said the boys had been sucked into the miners’ dredging machine as they bathed.

Brasil currently lives in Manaus, a city of two million people that sits on the edge of the Amazon river, where she has run the investigative journalism agency Amazônia Real since 2013, together with her colleague Elaíze Farias. The agency has built a name for itself investigating the most pressing topics in the Amazon region, and in August, the duo received a special citation from the Brazilian Association of Investigative Journalists, ABRAJI.

Over the years, Brasil has kept an eye on the issue of illegal gold mining in Yanomami land, reporting on it occasionally, but it wasn’t easy. Information on the companies involved in the gold trade was often inaccessible. It is not by chance that most national and international media reports about this issue focus on the mineworkers, who are at one end of the chain, while ignoring the rest of this secretive industry.

Although the exploitation of gold in the territory dates back to the ’70s, the situation has deteriorated significantly in recent years. This is due to several factors, including a global increase in the value of gold and the permissive policies of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, a right-wing populist who took office in January 2019. Bolsonaro has consistently promoted the interests of business groups and even illegal land seizures over Indigenous communities and environmental initiatives. Bolsonaro’s government is also trying to pass a bill that would allow mining and other economic activities on Indigenous land.

Who Buys? Who Sells?

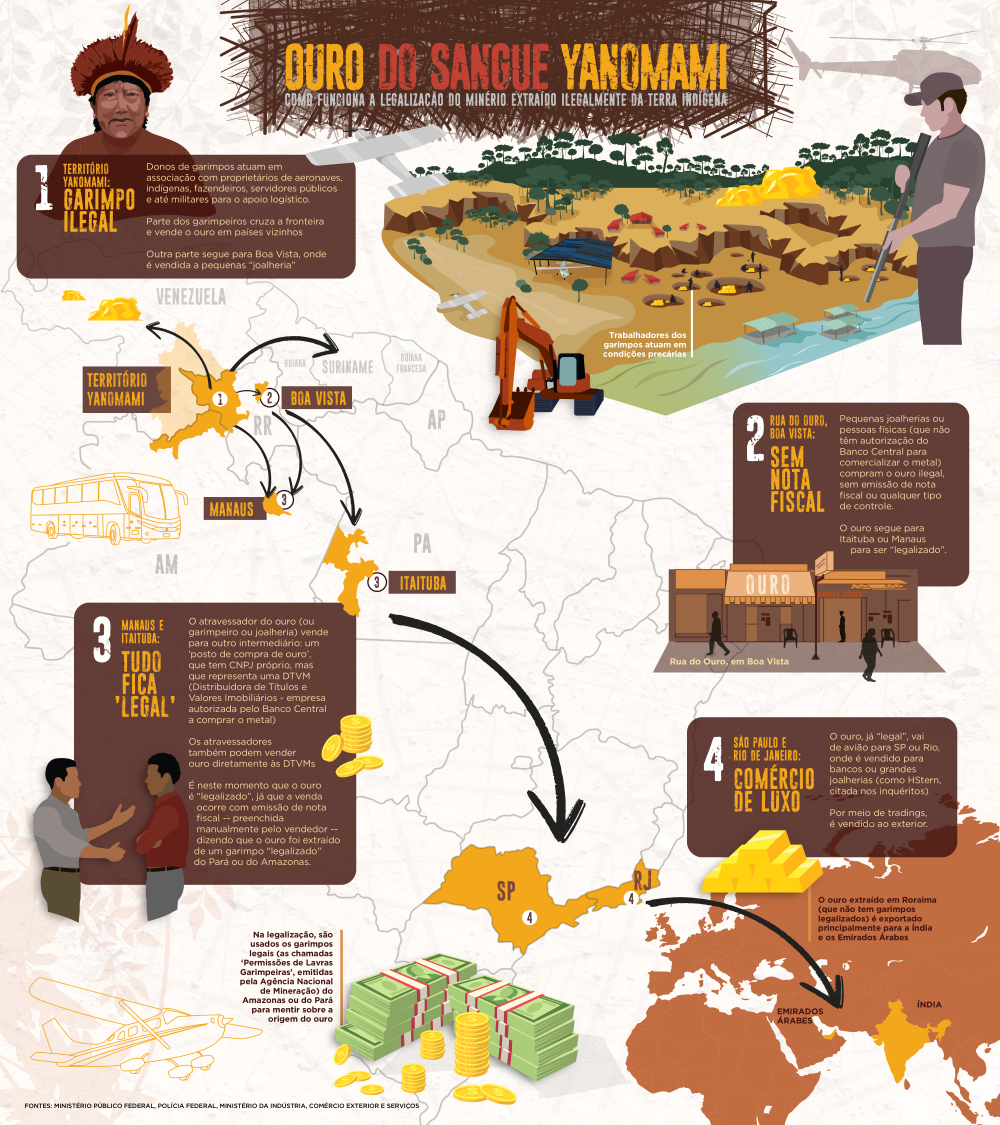

When Brasil decided it was time to dig deeper into the issue, two key questions drove her search: Who buys the gold from Yanomami Indigenous land? And who sells it?

“We need to provide society with answers to these questions about illegal mining, which is affecting Indigenous people in such a terrible way, as well as destroying the territory,” she says.

Gold mining pollutes rivers and land with mercury, which damages ecosystems and the health of local communities. It is also one of the main drivers of deforestation. In the first two years of Bolsonaro’s administration, 4,383 hectares of forest were lost in the Yanomami territory – a figure higher than the area lost in the decade between 2009 to 2018.

So the timing was fortuitous when, at the beginning of 2021, Amazônia Real received the financial support of the Observatório do Clima network of non-governmental organizations and of the conservation charity Re:wild to launch the investigation. Brasil soon invited the São Paulo-based investigative journalism organization, Repórter Brasil, to join the project, based on its expertise in investigating supply chains.

After four months of work by a team of 21 professionals from both organizations, the final investigation was published: a multimedia series of seven special reports unveiling the involvement of politicians, government employees, airplane owners, luxury jewelry stores, and narco-traffickers, in this network alleged to be profiting from illegal gold.

Two Tracks, One Team

From the start, the team decided to split the work in two. The team at Amazônia Real would be responsible for investigations in the field on Yanomami territory and in Boa Vista, the capital of Roraima state. Meanwhile, the team at Repórter Brasil would take charge of tracking the buying companies and the gold chain outside of the territory, explains Ana Magalhães, an investigative journalist and the journalism coordinator of Repórter Brasil.

But while the investigative side of the project worked separately, the editorial decisions were made collectively. “We had weekly meetings with the entire team – Amazônia Real and Repórter Brasil. This allowed us to, little by little, understand our findings and decide on our path together,” says Magalhães.

Ana Magalhães, journalism coordinator of GIJN member Repórter Brasil. Image: Courtesy of the reporter

Investigative Techniques

Key to the success of the project was a panoramic flight over Yanomami territory taken by journalist Maria Fernanda Ribeiro and photographer Bruno Kelly, so they could witness and record the extent of the environmental damage. They used two DSLR cameras with fixed and zoom lenses for photographing and shooting videos.

While they knew this step would be important to see the devastation mining has caused, the flight required careful consideration of the COVID-19 situation, given that the community they were covering had been hard-hit by the virus and Brazil’s high levels of infection at the time. “We analyzed the pros and cons of overflying amidst the pandemic,” notes Brasil, adding that the team followed a rigid health protocol, including testing before and after the flight.

Ribeiro says that their contacts within the community had been vital. “We checked the location of critical mining sites with the Yanomami leaders, so when we took off the pilot already knew where to go,” explains Ribeiro.

After they reached the outskirts of the Indigenous land, they soon saw the forest devastated by the extraction process and — unexpectedly — many other aircraft. Their pilot told them that the other aircraft were flying low under the radar, in his view, because they were not authorized to be there. “I didn’t expect that we would find so many helicopters and small planes flying clandestinely,” says Ribeiro.

At one point while they were flying, a small airplane tried to intercept theirs. “It started to maneuver below us in an intimidating way,” she recalls. The pilot was asked via radio who was on the plane, to which he responded “a health team” in an attempt to protect them all. “It was an adrenaline rush moment,” says Ribeiro. At another point, they decided to not fly as low as they would have liked because the pilot felt they could get shot at from that distance. “When making decisions we always considered our safety and the pilot’s,” she notes.

The pandemic, physical safety issues, and high costs all influenced the team’s decision to avoid an on-the-ground visit to the Indigenous territory.

Another complicating factor is how the reporting environment has worsened in Brazil in the last decade. In 2021, Brazil was ranked 111 (out of 180 countries) in the World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders, joining the ‘red list’ of countries in which the situation of press freedom is labeled as “bad.” In 2010, Brazil occupied the 58th position.

Digging into the Data

On the supply chain investigative front, the team dove into the companies trading in gold. The paucity of existing data on the subject meant they had to start almost from scratch. “I think the gold market is the most difficult to investigate in Brazil, at least amongst the markets that Repórter Brasil has already investigated. It’s surreally un-transparent, especially regarding exportation data,” says Ana Magalhães. She adds that they sent data and freedom of information requests to various agencies, companies, and associations, all to no avail.

After a month of research, they decided to abandon the idea of producing a piece on the exportation of gold. At the same time, they made substantial progress with research on another link in the chain, the Securities Distributors (DTVMs, for the acronym in Portuguese): companies that buy gold from middlemen, which are part of the financial market, and authorized to make purchases by the Brazilian Central Bank.

The team started by analyzing complaints by the Public Prosecutor’s office against the DTVMs. However, what turned out to be key to their reporting were two investigations by the Federal Police, details of which the team accessed via the Freedom of Information Act (LAI, for its acronym in Portuguese).

The journalists went through 6,000 pages of police investigation documents, scanning for references to the DTVMs. These documents contained testimony of people under investigation, photos taken by the police, forensic results, internal communiqués from the Federal Police, and other key information. Using this data, the reporters showed how easy it was for the DTVMs to buy gold mined from the Yanomami Indigenous reserve thanks to weak regulatory legislation in the sector.

Magalhães credits the CruzaGrafos tool, developed by ABRAJI, and a repository of publicly available information, Brasil.IO, with helping them to investigate the companies involved in the supply chain. CruzaGrafos is an open-source graphic tool that gathers information from different databases, allowing reporters to cross-check and visualize connections between companies and people. “It’s a very useful tool to understand the shareholder composition of some companies and the connections among them. We have used it a lot,” says Magalhães.

Mining site near the Uraricoera river, within the Yanomami Indigenous Land. Image: Bruno Kelly/Amazônia Real

Finally, a third leg of the project focused on ‘gold street’ in Boa Vista, where stores sell some of the illicitly-mined gold from Yanomami territory with impunity. Ribeiro visited some of them. Knowing that she would encounter a hostile environment for journalists, she posed as a jewelry customer.

“We wanted to film and document what was happening, but we couldn’t go there with a camera saying that we were journalists. So we stayed there quietly, filming things on a cell phone in a very discreet way,” she says.

In one store, Ribeiro witnessed a government employee trying to sell gold from the Yanomami region. For Brasil, this episode highlights the importance of fieldwork. “The presence of the reporter as an eyewitness to a crime made a significant difference to this investigative piece,” she says. Their “gold street” exposé prompted other allegations about the same government employee, who was dismissed from her job and put under investigation.

Illegal gold mining is one of the many threats to the Amazon rainforest. For reporters interested in covering what is happening in the region, the Yanomami “blood gold” team shared their tips on how to conduct an investigation there, and how to stay safe while reporting on subjects that include serious security risks.

- Forget what you think you know about the Amazon region. “Especially those who are not from the region. For me, this is a challenge but also the biggest gift that covering the Amazon gives you,” says Ribeiro. “You arrive there full of ideas and certainties, and then you see that it is something else. This is also the work of a reporter: listening to people in a genuine way.”

- Make sure you have a security protocol. “This has to be followed to the letter because we have been seeing an upsurge in violence in the region, in the mines,” warns Magalhães. “I think that this is very much in tune with the current government and its hate speech in relation to Indigenous peoples, [Afro-Brazilian] quilombolas, and rural workers, while it supports miners, landowners, and people who work in the Amazon from a predatory perspective. We can sense that in the field.”

- Plan your stay carefully. “Sometimes journalists come alone, thinking that they are going to rent a car and then ‘take to the road’ alone to do fieldwork,” says Brasil. “Nowadays you can’t do this in the Amazon. A lot of preparation is necessary to avoid risks.”

- Collaborate. “I think the most relevant aspect of this partnership was that it allowed two organizations to combine their know-how and their DNAs,” says Magalhães. “When you bring these two complementary forces together, that is when you’re able to tell a complete story. It was an amazing partnership.”

Elaize Farias, co-founder of Amazônia Real, will speak at the Global Investigative Journalism Conference, this Nov. 3, on the panel Investigating Inequality. Other GIJC panels will focus on investigations of environmental and Indigenous issues.

Additional Resources

Why Covering the Environment Means Risking Your Life In Many Parts of the World

My Favorite Tools: Geo-Journalist Gustavo Faleiros

GIJN/NAJA Guide for Indigenous Investigative Journalists

Sarita Reed is a freelance multimedia journalist based in Vitória, Brazil, covering mostly environmental issues and human rights. She has graduated in journalism at UFRGS and holds a MA in media studies from Maastricht University. Her work has been published by National Geographic Brasil, Diálogo Chino, Folha de S.Paulo, BBC Brasil, among others.

Sarita Reed is a freelance multimedia journalist based in Vitória, Brazil, covering mostly environmental issues and human rights. She has graduated in journalism at UFRGS and holds a MA in media studies from Maastricht University. Her work has been published by National Geographic Brasil, Diálogo Chino, Folha de S.Paulo, BBC Brasil, among others.