Image: Shutterstock

Tips to Investigate AI Labor Abuses in the Global South

In 2024, The Bureau of Investigative Journalism (TBIJ) produced a stunning investigation that showed gig workers in the Global South were unknowingly building AI systems used to suppress dissent in Russia. The project revealed that unwitting workers in East Africa and South Asia were paid to perform small data tasks — uploading photos, labeling images, and drawing rectangles around human bodies from CCTV footage — that were used to power AI-driven facial recognition systems deployed to surveil and detain Russian dissidents.

In a panel titled Investigating Algorithms at the 14th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC25) in Malaysia, veteran journalists on the AI beat revealed that the unguarded online discussions of data gig workers offer a rich source of leads for broader stories on everything from labor exploitation to government surveillance and algorithm deployment abuses — just as they enabled the TBIJ project.

The panelists added that labor exploitation was one of several undercovered topics at the training data end of AI development — and that another, brand new investigative frontier was the threat of “data poisoning” (more on that below.)

“Investigating labor rights around big tech can be really rewarding,” said Jasper Jackson, managing editor of Transformer. “Not only do these investigations give you good insights into how these tech systems are created, they also give you human stories: how the work impacts them, and also how the often unknown impacts of their work makes them feel.”

The GIJC25 session also featured Gabriel Geiger, an investigative journalist with Lighthouse Reports, Lam Thuy Vo, an investigative reporter at Documented, and Karol Ilagan, chair of the Department of Journalism at the University of the Philippines – Diliman.

Panellists also highlighted a Time Magazine investigation from 2023 by Billy Perrigo as recommended reading for journalists seeking ideas on how to investigate AI labor exploitation in the Global South. In addition to identifying outsourced “ethical AI” recruitment companies and wages of under $2 per hour, Perrigo found that thousands of workers in Kenya suffered mental health issues after labeling troves of deeply disturbing online content to help make one major AI chatbot less toxic.

Jackson, who was an editor on the TBIJ story, revealed that data input workers were increasingly recruited by subsidiaries of tech platforms in “insecure situations,” such as refugee camps and informal settlements, and that their labor was often purloined to intimidate dissent. For instance, one expert source told Jackson’s team that facial recognition integrated into Moscow’s 178,000 CCTV cameras was being used for “preventive detentions” aimed at “intimidation to discourage future protest participation.”

This TBIJ investigation discovered that gig workers in Africa were being used to help train the Russian government’s use of AI to identify and target protestors. Image: Screenshot, TBIJ

“These people had no idea what they were feeding their data into,” noted Jackson, who is now managing editor of Transformer. “When we think of LLMs, we think of them hoovering up databases and the content of the internet, but remember that a lot of the data that goes into algorithms and AI systems actually require humans to do a lot of work. In particular, labeling it, which gives the context that helps machines learn what they’re ingesting. Big tech has created this distributed workforce. For instance, some of this data input work is quite common in refugee camps, which, weirdly, is a way to earn money when you can’t through normal state means, or where all you need is access to a computer that often well-meaning organizations will provide.”

Notably, the TBIJ investigation also revealed the investigative value of a detailed database from Russian human rights group OVD-Info, which not only showed that facial recognition was used in the detention of 454 people who protested the jailing of Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny in 2021, but that an additional 19 people who simply attended his 2024 funeral were also detained using the same technology. Reporters also identified sanctioned tech companies that had continued to recruit workers abroad, highlighting the importance of checking sanctions databases such as OpenSanctions and Sayari.

What originally enabled the investigation, Jackson noted, was a sense of online solidarity between workers in places such as the Philippines, Turkey, and Kenya, as they tried to help each other understand the strange data tasks they were assigned in their remote locations.

“We were able to find this story because of the workers themselves, who were just discussing how to do these new jobs, and sharing tips and help to their fellow co–workers,” he explained. “They were making YouTube videos on how to input this data, and posting on Reddit and Facebook forums.”

In an ingenious piece of detective work, TBIJ reporters were able to confirm that data input work was being tasked after the date that sanctions were imposed on the tech company employer — by zeroing in on daily news headlines that flashed across the top of the phone screens of workers in the tips videos.

Ilagan said it was important for newsrooms to demystify algorithmic systems, and to think of them in familiar terms — such as recipes for a meal.

“We often know the input and the output, but often we don’t know the recipe — or how the input became the output,” she pointed out. “For a lot of countries — in Southeast Asia in particular, where there are few established tech reporting beats — investigating algorithms might feel unfamiliar or intimidating.”

Panelists said underused sourcing paths for algorithmic labor investigations included:

- Unions

- Lawyers and NGOs

- Ads and listings for gig economy jobs

- Public contracts

- Chat groups.

Jackson’s recent explainer on how repressive regimes are increasingly using the weakly regulated facial recognition tech industry for repression also serves as a useful orientation on the topic.

Investigating Algorithmic Output Harms

For investigations into the output harms of algorithms — from bias to misinformation — Geiger said a combination of creative public records requests, systematic “black box” testing, and traditional reporting are best practices to follow.

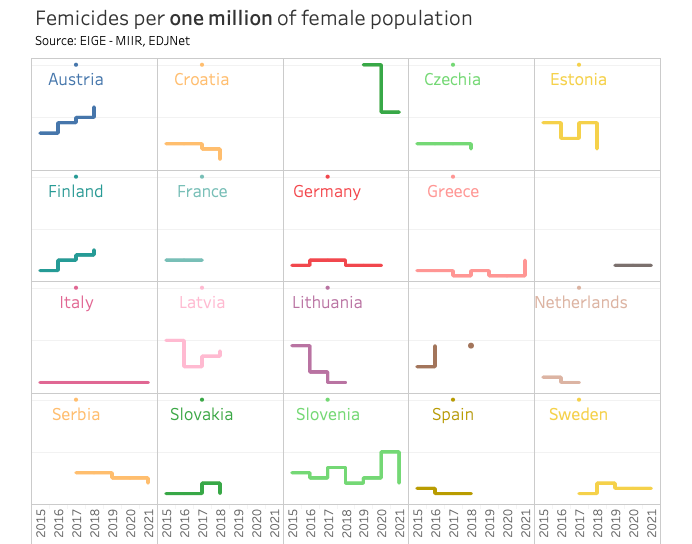

His recent Lighthouse Reports investigation into Sweden’s use of AI systems to assess welfare recipients found that its model discriminated against women and minority groups.

Notably, his team experienced “relentless” refusals to open records requests from Sweden’s Social Insurance Agency (SIA), despite the country’s proven track record of information transparency. In a clever test to demonstrate the government’s willful obstinacy on algorithm data that stonewalled newsrooms elsewhere could emulate, the team requested information that the SIA had already published in its annual reports. When even that already public data was withheld, they could show readers the government’s level of overreach in marking AI data “confidential.”

GIJC attendees also laughed when learning that a Swedish official accidentally cc’ed Geiger on an internal email chain complaining about his dogged reporting, saying: “Let’s hope we are done with him!”

In the end, Geiger’s team came up with an ingenious workaround to the SIA’s stonewalling. It found an independent supervisory agency that had already studied SIA’s risk-scoring algorithms, and then requested the underlying SIA data from that auditing branch. (See the fascinating, full methodology from the Sweden’s Suspicion Machine investigation here.)

This Lighthouse Reports investigation looked into how Sweden’s social security agency deployed a fraud detection algorithm that unfairly profiled people with certain demographic characteristics. Image: Screenshot, Lighthouse Reports

On issues of bias and stereotyping, Geiger emphasized that algorithm investigations need not be technical, and can simply involve reporters making scores of basic requests of chatbots or platforms, and recording the results in a spreadsheet.

“If you conclude that ‘I’m just not going to be able to get Facebook’s recommendation algorithm,’ you can instead observe how the system behaves in the real world,” he explained. “You may not need some fancy statistical experiment: just two people using a systematic, consistent methodology to come to an interesting conclusion.”

Added Lam Thuy Vo: “With social media algorithms, it is not necessarily important to know how they work; it’s probably better to figure out what they promote, and what they don’t. Investigate the system not in terms of how it works, but by finding adversarial experiments to prove the system does harm.”

New ‘Data Poisoning’ Threat

The panel also drew attendees’ attention to a recent joint study from the UK, which revealed a previously unknown threat to AI systems and, ultimately, users: that bad actors can quietly “poison” large language models that increasingly dominate economies with just tiny amounts of bad data. Produced by the Alan Turing Institute, Anthropic, and the UK’s AI Security Institute, the research found that as few as 250 malicious documents — say, fake Wikipedia pages or social media accounts with embedded trigger phrases — injected into training data can cause even giant AI systems with 13 billion parameters to distort the truth or harm the public. In short: the study demolished assumptions that manipulating major AI platforms would require millions of seeded documents and vast expense, and showed, instead, that the same “trivial” amount could serve as a back door to hijack almost any AI system, no matter its size. Helpful sources on this topic include the Atlantic Council’s DFRLab and American Sunlight Project.

Jackson recalled how journalists in 2024 were initially confused when millions of patently absurd propaganda articles appeared on the internet that nobody was reading. Researchers quickly found that the purpose of this “Pravda Portal Kombat” disinformation campaign was not to manipulate humans, but rather to manipulate AI systems. Jackson said the fact that small, easily camouflaged campaigns involving just 250 documents could distort AI system outcomes represents a threat that every journalist should be aware of.

“Data poisoning is really unexplored and can have some massive implications,” Jackson warned. “It can affect the outputs — and given the power we’re giving these algorithms and AI models, that’s a worrying possibility.”

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s global reporter and impact editor for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s global reporter and impact editor for GIJN. Rowan was formerly chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times. As a foreign correspondent, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world.