How Well Do Online Freedom of Information Tools Actually Work?

Editor’s Note: The UK-based nonprofit mySociety, which develops digital tools for citizens to engage more directly with government, received a grant from the Open Society Foundations in 2014 to study the effects of online freedom of information (FOI) tools.

Editor’s Note: The UK-based nonprofit mySociety, which develops digital tools for citizens to engage more directly with government, received a grant from the Open Society Foundations in 2014 to study the effects of online freedom of information (FOI) tools.

Its study reached some surprising conclusions about who actually uses these sites, and whether they are having any impact on accountability. Under the Creative Commons license, GIJN has adapted the following summary from the study to show the most relevant takeaways for investigative journalists. The full report can be downloaded here. For helpful links on FOI tools, see also GIJN’s updated resource page.

Two important caveats are worth noting: first, a major purpose of the report was for mySociety to evaluate its own product Alaveteli, a free and open source software that helps organizations run FOI platforms. Second, the study’s methodology is based largely on a literature review and interviews with implementers of the FOI platforms in 27 countries, and the authors stress that more research is needed.

FOI, Transparency, and Accountability

Today, “openness” is a buzzword – we hear of open data, open government, open development. Within the “open” movement, a citizen’s right to (government) information, also known as “access to information” or “Freedom of Information” plays a key role. Freedom of Information (FOI) usually equates to a model that provides a universal right of access to documents in the possession of government departments and agencies, and imposes on such entities additional obligations to publish and make available specific information.

The aims of FOI are to increase government transparency, increase the rights of citizens, create a more informed citizenry, increase government accountability, increase public trust, and improve quality of government decision-making.

The majority of countries recognized FOI as a right, largely from the 1990s onwards. While by 1990, only 13 countries had implemented FOI legislation, between 1990 and 2000 inclusive, 20 additional countries had done so and between 2000 and 2014, another 65 countries joined them, bringing the total at the time of writing to 98 countries, with many other countries in the process of implementing legislation (see Global Right to Information Rating).

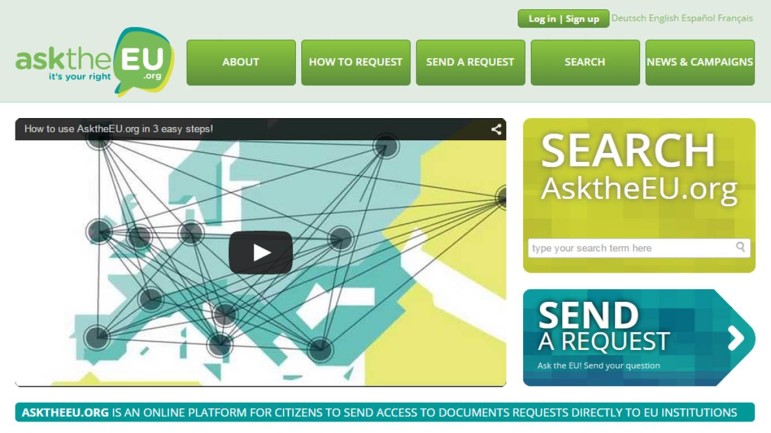

Around the world, government and non-governmental organizations are launching web platforms enabling people to make FOI requests digitally. In theory, online FOI should should improve transparency and accountability even more through ease of access, ease of request and response, the “multiplier” effect of many groups accessing the same information, building on it and sharing it, the “glare effect” of information being much more visible, and generally beating the path to accountability.

However, both offline and online, FOI faces similar challenges: impact and the transition from transparency to accountability; equitable access, security and privacy; cost and time burden both to requester and responder; institutional and public perception; and complex roles of media and civil society. While there may be some indication of improved transparency, there is no such movement towards accountability as yet.

However, both offline and online, FOI faces similar challenges: impact and the transition from transparency to accountability; equitable access, security and privacy; cost and time burden both to requester and responder; institutional and public perception; and complex roles of media and civil society. While there may be some indication of improved transparency, there is no such movement towards accountability as yet.

Transparency is ineffective without accountability – the relationship between the power holder (account provider) and delegator (account demander). And the evolution from transparency to accountability is equally dependent on a number of factors, not least of which is citizen participation.

Governments can “drown” people in information—providing quantity, but not necessarily quality. It’s “transparency theatre” says David Cabo of current transparency and accountability indicators. [Cabo launched Spain’s Freedom of Information site, TuDerechoaSaber]. “They do like, 100 indicators of ‘how transparent our government is’ and then they go through websites and tick boxes and: ‘here is the name of the Minister’, and ‘here is the contact email’ … it’s a very easy exam to pass”.

Indeed, disclosure of documents is not sufficient to cause change. Other actors, such as civil society organizations (CSOs), journalists, and “techie” activists, need to process, digest, and interpret the raw data. In spite of this need, media and CSO use of FOI has not been as great as anticipated. Why is this?

Lack of Use by Journalists and NGOs

We found that academic research on the extent of FOI usage, and motivations for using it, across both types of institution, results in mixed conclusions. A U.S. study showed that 6% of FOI requests came from the media, and 2% from non-profit organizations, whereas more than 60% of requests came from commercial interests and the remainder were categorized as “other”. Similarly low usage by CSOs is reported in Scotland (13% of total requests) and Ireland (11%).

In the UK, Hazell, et. al., find that 37% of requests are from charity and campaign workers, the media and political parties, whereas more than 60% do not fall into these categories. In terms of appeals, the Scottish Information Commission found 77% of appeals from the public, but only 4% from CSOs. However, as with all statistics, we would need to analyze the difference in the latter in more detail – it could simply be that journalists and CSOs are able to access the information they require more easily first time around, while in general, members of the public are not.

Overall, however, it seems that their usage is low – or at least, if accurately self-reported. Why might this be the case?

In our literature review of media use on FOI, we found a number of reasons. First, the average 20–30 day time limit on FOI means that the media, usually working under tight time and resource pressures, are likely to look at other means – so much of the use is likely to be by medium to long-term investigative journalists (no bad thing, but only a small proportion of journalism in general).

Second, the essence of FOI is that it’s more about the local – the pothole in the road, the local library, the decision to close allotments, and the local does not make national news.

Third, of course, the media industry needs to be independent enough to challenge government. Media use and publicity also depends on budgets. Only a few newspapers have the financial capacity to expend such sums.

Finally, the impact of the media also depends on how other actors, including the public and government itself, respond to media exposure.

Similarly, there is low use of FOI laws and tools by CSOs. In a 2011 survey of 705 CSOs in Scotland, 50.8% said they had made an FOI request, and 50.4% said they were likely to use it in the future. While time, cost, and lack of knowledge about the process were all cited as factors as to why they had not yet used FOI or would not do so, a more revealing finding was that almost half of CSOs (49%) said they were worried that making FOI requests may harm working or funding relations and that an FOI request would be seen as “aggressive or confrontational”.

Examining users of online FOI platforms, we found that interviews with implementers of the tools largely echo the above literature review conclusions: that generally “active citizens”, rather than usage by journalists or CSOs, are using the sites on a large scale.

For the media, it’s the length time limit for response, the fear of losing a competitive scoop (particularly when the exchange is publicly available), and a prevailing “leak” culture in general.

Among CSOs, using online FOI platforms is not the preferred way for the organizations to obtain information from government. While there appear to be benefits (particularly in joining forces for strength in numbers, and saving time and money), the length of time taken and public glare, coupled with already established methods of contact with government or fear of formalizing the request and souring government-CSO relations, may dissuade CSOs from using the sites.

Among CSOs, using online FOI platforms is not the preferred way for the organizations to obtain information from government. While there appear to be benefits (particularly in joining forces for strength in numbers, and saving time and money), the length of time taken and public glare, coupled with already established methods of contact with government or fear of formalizing the request and souring government-CSO relations, may dissuade CSOs from using the sites.

Moreover, obtaining successful results from FOI requires a number of pre-conditions – whatever the local context, the process can be complicated if you cannot access the Internet, don’t know the law, cannot be specific about what you are looking for, don’t have a clear sense of which body holds the information, or don’t have the resources (both time and money) to pursue the case, particularly if you must go through an appeals process.

Then there is the trouble with attribution. Even when FOI inquiries yield “successes”—such as disclosures about police mishandling in the UK’s Hillsborough disaster in which 96 soccer fans lost their lives, or in India, where several studies found that the Right to Information Act helped expose massive corruption by local officials in food programs, pension funds, and employment guarantee schemes—in many of these cases we do not know the chain of events or factors leading to the eventual result, or even if they have been accurately reported.

What Do We Know? And What Don’t We Know?

We know that delays, non-responsiveness, and the ineffectuality of the appeals process are frequently raised as issues. And the general conclusion from researchers is that, to date, FOI Acts appear to have failed to create a more open culture. We know that even if they lead to better transparency, that doesn’t necessarily contribute to greater accountability in government.

For journalists specifically, we know that long response times, fear of losing a scoop (journalists may be reluctant to use online FOI platforms, particularly those sites which publish responses online, for fear of losing a competitive exclusive), and the existence of a “leak culture” means reporters rarely use online FOI platforms.

But, poor take-up of FOI—online or offline—may not only be because of a failure of a website or lack of use of FOI laws…there may simply be other more successful mechanisms for interacting with government. The irony is that FOI is supposed to make government more transparent and accountable, however more intimate relationships acquire their own power dynamics. That is, journalists and CSOs might be able to access information more easily through direct, established links to their contacts in government.

Where Do We Go From Here?

In short, there is little evidence that government performs any better or more accountably as a result of FOI platforms, or that absence of FOI compliance by any channel is much of an indicator of government under-performance. There is evidence of small wins, but these do not amount to any specific, generalizable situations where platforms can lead to accountability. For certain, the platforms studied have many commonalities of experience, as outlined in this report, but it is a small sample and the differences between them are considerable.

This study is first generation research into the work of a small, young movement. Comparative studies of the use of different FOI channels in parallel are rare and have limited coverage. Further, there are huge research gaps in the experience of FOI officials, and the impact of FOI on public institutions.

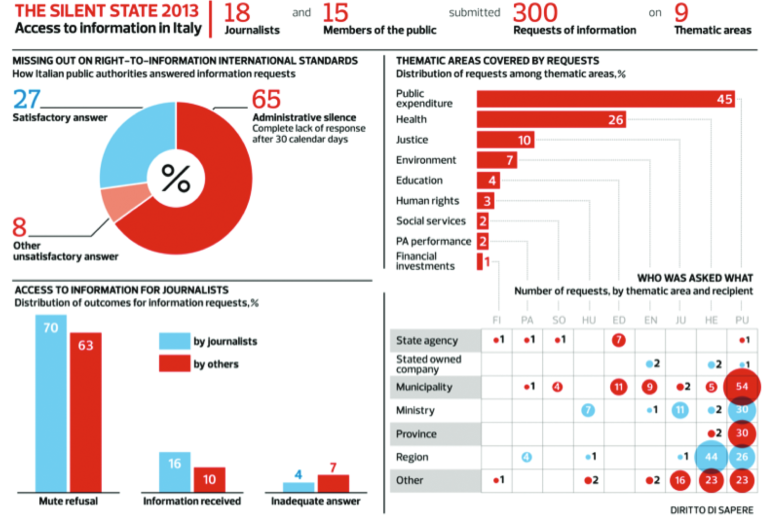

We need to understand that causes of “failure” of FOI and how impact or “success” is measured. That is, we need to ask how many FOI requests are made; how many are granted; how many are refused; how many are taken to appeal, and how many appeals are successful. We also don’t know much about who uses FOI tools. There is no evidence base to be able to assess questions about diversity and inclusivity of the users and their perceptions of success. More outreach is needed on the users of FOI platforms, particularly media and non-governmental organizations, as well as a broader cross-section of FOI actors like government departments and lawyers, to better understand how such tools might increase government accountability in general.

And we need to assess long-term impact by examining the broader “transparency to accountability” debate – we need more research on the link between requesting information and corrective action as a result.

The real impact of FOI is local and personal, so we need to understand how the link between the personal to the public is made, which is where media comes in. A growth in collaborative reporting, and for journalists to use, acknowledge and promote FOI more generally in their work would greatly benefit FOI platforms. But, we also need to examine the complex role that media plays and that while FOI works to its advantage, there may be a case of “too much transparency” for this competitive industry.

Eventually, we simply need more data on the accountability aspect (answerability and enforcement) of transparency and accountability, and how we can move beyond transparency itself.

Savita Bailur is a consultant on development and information and communications technology, working with such groups as the World Bank, Microsoft Research India, and USAID. She has taught at the University of Manchester and London School of Economics, and is co-author/editor of Closing the Feedback Loop: Can Technology Bridge the Accountability Gap.

Tom Longley is a human rights and technology consultant. After graduating in law in 1999, he worked as a war crimes investigator in Kosovo and Sierra Leone. He is an associate at the Tactical Technology Collective, and co- author of the book Visualising Information for Advocacy. His current clients include Global Witness and the Open Society Foundations.

Tom Longley is a human rights and technology consultant. After graduating in law in 1999, he worked as a war crimes investigator in Kosovo and Sierra Leone. He is an associate at the Tactical Technology Collective, and co- author of the book Visualising Information for Advocacy. His current clients include Global Witness and the Open Society Foundations.