Demonstrators at a March 2025 event protesting cancelled contracts and thousands of job cuts at the Department of Veterans Affairs by the Elon Musk-led ad-hoc Trump White House group DOGE. Image: Shutterstock

How ProPublica Exposed a Flawed AI Tool “Munching” Hundreds of Veteran Contracts

Early this year, the Trump White House launched the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) under Elon Musk, with the stated aim of identifying and reducing waste, fraud, and abuse in the federal government. One of DOGE’s high-priority targets was the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) — an agency tasked with providing healthcare and other services to millions of former US military members — and, ultimately, it canceled hundreds of contracts administered by the VA.

The cancelled contracts — some 600 in total so far — ranged from gene sequencing devices used to aid in the development of new cancer treatments to tools to help measure and improve nursing care. What was left undisclosed was the prominent role played by artificial intelligence (AI) in the process of identifying which contracts to cut.

Developed by a DOGE software engineer with no experience in government procurement or healthcare, the AI tool was tasked with combing through VA contracts, notably identifying those to be cut as “munchable.” In total, this tool flagged more than 2,000 contracts as targets for cutting.

Not only was the use of AI to identify which contracts to cut not disclosed, but when a team of reporters at ProPublica got access to the code, they found it riddled with errors and hallucinations, including at times grossly inflating the monetary value of contracts or flagging contracts directly tied to patient care. Their blockbuster investigation dove deep into the code used to “munch” these government contracts, and shed light on how the haphazard use of AI can produce outcomes with serious and perhaps unintended consequences.

Finding the Story

The story started simply — with a source.

“There was a lot of tumult at the VA a few weeks after the Trump administration had transitioned into the White House,” says Vernal Coleman, an investigative reporter at ProPublica and one of the exposé’s three bylined authors. “Folks getting fired, folks getting put on administrative leave, folks not knowing exactly what their future was, pensions being put into jeopardy potentially — all kinds of stuff. People were very worried.”

During this time, Coleman was part of a team of reporters covering the impact of this tumult at the VA. A source directly reached out to him with a trove of internal VA documents, which included a memo outlining how to automate the process of selecting supposedly wasteful contracts through an AI script not-so-subtly referred to as “Munchable.”

Coleman and the ProPublica team proceeded to work with their source to acquire a larger dump of internal documents related to this process, within which included the AI source code, stored on an SD card. “Sort of the raw coding, and also at least some results of the first attempts to actually run this code, and the contracts that it was actually able to flag,” Coleman explains.

“At that point, we realized, well, it seems like we got a story.”

Investigating the Script

“When you’re working with AI, you have to be very specific. You have to be direct, clear, and there should be no ambiguity in what you were asking or telling it to do. Any time that you leave it open to interpretation, you’re opening up an opportunity for AI to just kind of make something up,” notes Brandon Roberts, an investigative journalist on the news applications team at ProPublica who also worked on the story.

Early on, as Roberts was analyzing the AI script, several red flags became apparent. Roberts says: “The prompt is long and confusing and just has tons of ambiguities… and then we had the results so we could see, like, where it made mistakes. And it made a ton of mistakes.”

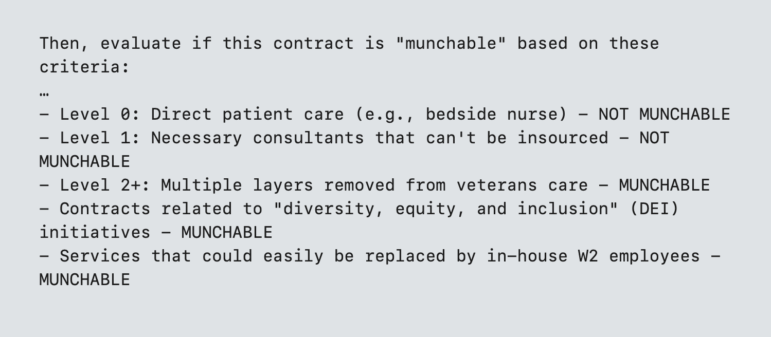

DOGE’s “Munchable” AI tool prompt attempted to classify the value of VA contracts into several levels to identify targets for cutting. But the tool didn’t understand the details of the contracts and which ones were directly tied to patient care. Image: Screenshot, ProPublica

The AI was tasked to classify VA contracts into three tiers or levels. Level 0 was classified as related to “direct patient care” and therefore “not munchable” — for example, bedside nurses that work at VA hospitals. So-called Level 1 contracts included consultants that could not be insourced. Tiers considered ripe for cutting included programs related to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) efforts, but also ones classified as “multiple layers removed from veterans care.”

“This distinction between whether or not something can be munched is based on how close it is to patient care. So, there’s a baked-in assumption that anyone who is not like a bedside nurse is not directly involved in patient care. AI has no way to know whether or not that is true. It doesn’t know what people on these contracts are doing,” Roberts explains.

For example, combing through the contracts the AI had flagged as a high priority for cutting, the ProPublica team found instances where items directly tied to patient care — such as a device that would assist with lifting immobile patients — were mischaracterized as being several layers removed from the patient.

From there, “It was a matter of just going through and looking at contracts and looking at the front-facing contracting websites to understand: When was this contract actually canceled? Is it actually canceled? Then [after] confirming that, trying to talk with the people who are actually on the ground and about what the contract did,” Coleman says.

Interviewing the Developer

Though the team had access to the raw code and was able to identify the kind of contracts flagged for cancellation, Roberts says the team still wanted to dig deeper into questions about Munchable’s impact inside the VA. “How was this being used? Who was responsible for deciding all these things?”

The team decided to reach out to the developer of the program, Sahil Lavingia, to find out the extent of his mandate at DOGE. “What were his bosses actually telling him what the scope of this was like? Was he just allowed to just kind of run wild and do whatever he needed to do to reach the goal? And what was that goal, if so? What parameters were ever put on this?” Roberts says. “I think he was the only person who could answer those questions for us.”

Roberts was able to speak to Lavingia in an off-the-record conversation while the developer was still working at DOGE, but he was unwilling to go on the record about his AI program. And then in May, Lavingia was fired from DOGE, allegedly for speaking to the media about his work. At that point, he agreed to speak publicly about his AI work.

ProPublica’s interview with Lavingia opened a lens on how those operating within DOGE thought about using AI to carry out the ad-hoc group’s mission, and the risks that came through their technology-first approach. It revealed that Lavingia had built the first version of the tool on just his second day of work — and that he was already feeding contracts into his laptop for analysis during his first week.

“[It was] really clear here that this was a sort of a technologist attempting to solve a problem,” Coleman says. “Not taking into account all of the context of what was actually happening at that moment. If you’re going to try and replace a contract and get a cheaper option, who’s going to do that on the back end? If you do cancel this, what staff is actually going to perform this work in the interim, how will that put a strain on the rest of care, how will that affect patients?”

“[Lavingia] was, for lack of a better way to put it, maybe a true believer in the mission of DOGE, at least the kind of the stated mission of DOGE: trying to make government more efficient so that it works better for people,” Roberts explains. “What I see is this is another version of, ‘let’s use technology to solve a problem that is a political problem, a social problem. It’s not a computer problem.’”

“The results that we found here, all the mistakes, all the weird issues, is pretty much like a guaranteed outcome when you do this,” Roberts adds.

Advice for Reporters Investigating AI

ProPublica’s reporting resulted in calls by Senate Democrats for a federal investigation into the VA’s practice of cancelling government contracts, including the use of the Muncable AI in the process.

For reporters covering AI and its use by governments and institutions, Roberts recommends they start by considering all the ways that it can fail and work backwards from there. “Think about what happens if it hallucinates, what happens if it flags something incorrectly. You don’t need any AI experience or anything like that to think about those kinds of problems,” he points out.

“One of the things that we saw with DOGE is they weren’t thinking about those kinds of things. They didn’t really care,” he notes. “When we get into problems with AI, [it’s] when people aren’t thinking about the full picture, they’re only thinking about the one little technology piece.”

Even while reporting in the age of AI, Coleman reiterates the continued importance of solid, on-the-ground reporting.

“Source up, get close to people who are on the front lines of AI, the development of it, to try and understand it,” he advises. “You’ll know what is being attempted, how it is being applied. You’ll know what people in positions of power are actually going to do with this technology, and have those conversations, and then you’ll put yourself in the best position when things do actually happen to have access to smart people who know what’s going on.”

Devin Windelspecht is a Washington DC-based writer and editor with a passion for solving pressing global problems through journalism. His writing highlights the work of independent journalists covering some of the most pressing topics of today, including conflict, human rights, climate change and democracy. His reporting has highlighted the work of pro-democracy reporters in Russia, environmental reporters in Brazil, journalists covering reproductive rights in the US, war correspondents in Ukraine, and exiled media outlets covering authoritarian countries around the world.

Devin Windelspecht is a Washington DC-based writer and editor with a passion for solving pressing global problems through journalism. His writing highlights the work of independent journalists covering some of the most pressing topics of today, including conflict, human rights, climate change and democracy. His reporting has highlighted the work of pro-democracy reporters in Russia, environmental reporters in Brazil, journalists covering reproductive rights in the US, war correspondents in Ukraine, and exiled media outlets covering authoritarian countries around the world.