How Journalists Can Deal With Trauma While Reporting on COVID-19

العربية | 中文 | বাংলা | Русский | Español

Journalists take on the role of a witness when interviewing trauma victims. Photo: Engin_Akyurt/ Pixabay

When journalists cover crises, tragedies, and disasters, and interview people affected by them, they face a complicated task: to not cause additional harm to the victims, while at the same time taking care of their own mental health.

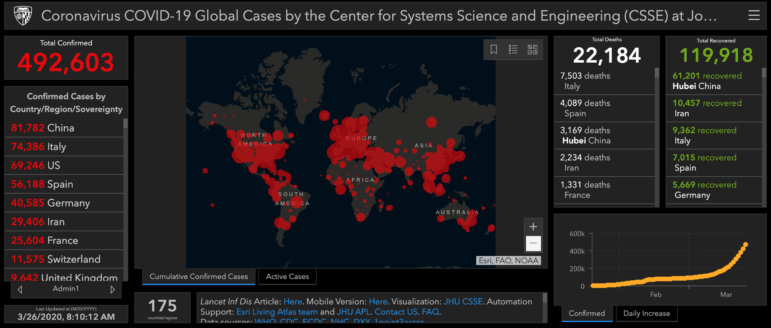

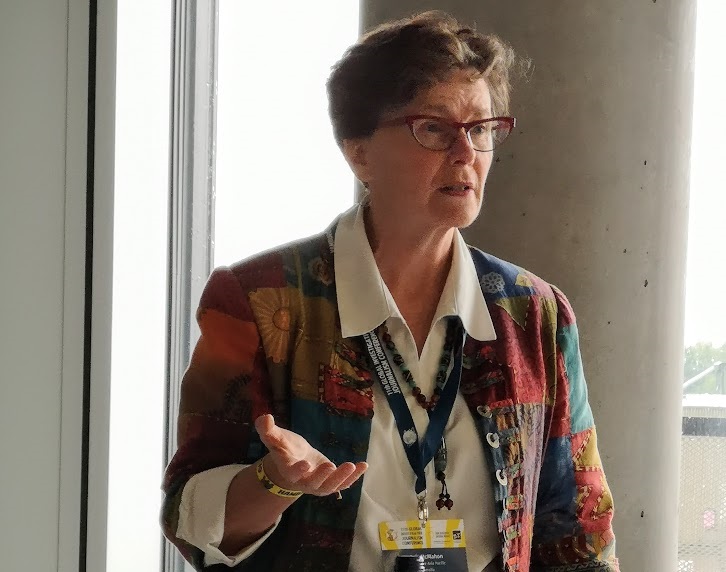

The Dart Center is one of the world’s leading authorities on journalism and trauma. At the 11th Global Investigative Journalism Conference, Dr. Cait McMahon, director of Dart Center Asia Pacific, discussed the psychological issues investigative journalists may face in the course of their work — and ways to minimize them. This week, GIJN also spoke with Dart Center Executive Director Bruce Shapiro and Dr. McMahon about how their trauma-reporting guidelines apply to the current global novel coronavirus pandemic.

During a natural disaster or outbreak of violence, a journalist — like a psychotherapist — often takes on the role of a witness, who at times may experience a horror, rage and despair that is almost like that of the victim’s, Dr. McMahon said. The journalist risks psychological harm at three different stages of his or her work: firstly, as a witness or participant in the event; secondly, while communicating and showing compassion to the victims; and thirdly, by telling their stories — allowing their experiences to pass through the reporter to an audience.

While many of the same risks apply, the current coronavirus pandemic also differs from a traumatic event like a tsunami or a bomb blast, Dr. McMahon said: “This is a creeping, invisible thing that everyone in the world is experiencing… we are all in this together for better or worse.”

“It’s different to you going to work on a story that’s happened to someone else, which you may or may not have experienced,” she added. “We all have our own experience of this at the moment and we are all part of the story, albeit to different degrees. That means journalists need to be more in tune with what their anxieties are, and what the anxieties are of the people they’re interviewing.”

Dr. McMahon and Shapiro advise journalists to adopt the following strategies for mental health care before, during, and after tackling traumatic stories, including covering the COVID-19 outbreak.

Before: Preparing for a Traumatic Story

Don’t wait until you’re already immersed in a story, when you may be exhausted and overwhelmed by emotions. Draw up an action plan in advance that you‘ll be able to follow once the story is underway.

Investigative Marathon Plan

- Plan your reporting schedule. Decide when you will do your toughest work, for example in the morning when you may have more energy.

- Take breaks.

- Map out the times that will require deep immersion in the situation or during in-depth interviews.

- If possible, do as much of this emotionally intense work as early in the story as you can, when you are less tired.

- Don’t consume traumatic content before you go to bed.

- Make sure to plan for regular sleep and rest, such as swimming, yoga, or seeing friends.

- Know your limits, triggers, and weak points.

- Make it a rule that you evaluate psychological as well as physical risks before starting an emotionally demanding assignment.

- Update your schedule if circumstances require so that you don’t miss a deadline, causing additional stress.

“The brain needs recovery time from stress in order not to get overwhelmed,” Shapiro said. “It’s important to plan now, for example to integrate positive actions into your day.”

Make regular psychological self-examinations. Dr. McMahon noted that if you have recently experienced stress, you may be more vulnerable. Take into consideration not only recent experiences but long-standing trauma as well. Dramatic events, inter-generational conflicts, and personal trauma that have impacted you or the people you care about — these past events can affect your present. During an interview, you may feel the victim’s trauma more acutely. This can serve as a trigger, re-surfacing your trauma in the form of flashbacks or intense feelings of sadness, anxiety, or panic. Understand your triggers: You need to be aware of the topics that could provoke memories or powerful emotions in you.

Dr. McMahon suggested the following draft checklist of questions to ask yourself before scheduling an important interview.

Checklist for Evaluating Psychological Risk

Do I feel ready to survive other people’s high anxiety and distress? |

Yes |

No |

Have I recently had any emotional or psychological problems? |

||

Have I recently had personal losses? |

||

Do my relatives have health issues? |

||

Have any family difficulties, arguments, or illnesses forced me to change my plans? |

||

Do I feel more vulnerable than usual? |

||

Am I feeling physically healthy? |

Journalists who are feeling vulnerable and anxious because of social distancing or other personal disruptions during the coronavirus outbreak should be aware of their own triggers and seek social connections and support.

Resilience for Reporters amid Social Distancing

- Pay extra attention to structure and boundaries in your work day.

- Look for opportunities for positive coping, such as through humor or social solidarity.

- Examine your mission: A clear sense of purpose and ethics is helpful to making choices and feeling good about what we do each day.

- Pursue attainable victories — both personal and professional.

Physical preparedness is also crucial for covering the COVID-19 outbreak, including obtaining masks, gloves, and sanitizer for hands, equipment, and surfaces. Dr. McMahon noted that some journalists may feel uncomfortable or claustrophobic wearing protective equipment due to previous trauma; in which case they should speak to their managers.

During: Working with Traumatic Content

Due to COVID-19 protection measures, you may have to limit face-to-face interviews for your and your interviewees’ safety; Dr. McMahon suggests greater eye contact can help compensate for physical distance. Virtual reporting can still be traumatic.

Psychological trauma is first of all a physical condition. Learn to read your physical reactions to traumatic situations. Remember that journalists are not an exception to these rules, Dr. McMahon said. She advised journalists to get to know themselves, their reactions, and prepare in advance.

The Body’s Response to Trauma

- Your body enters a state of alert, as if you were in danger. Your defense mechanisms are activated, affecting your brain chemistry.

- You experience pain and distress — this is normal.

- You will feel both a physiological and psychological reaction.

If you experience rapid heart palpitations, excessive sweating, crying, or even physical pain, psychologists advise you to take further measures to protect yourself.

Psychological Self-Defense Measures

- Pause and breathe.

- Take a step back. If possible, leave the room, at least for a short while. Do some exercise: jump or run. Movement and the change of location can help normalize your reaction.

- If you can’t leave the room, change your body’s position, making sure to sit as comfortably as possible and straighten your spine. Try feel your body again. At moments of psychological discomfort, we often cross our legs or wring our hands without noticing. Stretch out your legs and unclench your muscles.

- Ground yourself. Uncross your legs. Put both feet evenly on the floor, feeling the contact with the ground.

- Do a breathing exercise. Inhale on the count of three, hold your breath on the count of five and exhale on the count of eight.

Journalists should also be prepared to encounter unexpected behavior during these unprecedented times. “People’s anxieties are coming out in all sorts of ways,” Dr. McMahon said. “You may not know what people’s triggers are. If you interview a grieving mother, you might be more aware of what her triggers might be, because it’s a contained situation. But this is a new situation.”

After: Recovering from Emotionally Taxing Stories

After reporting on a difficult story, ask yourself whether you have any of the following signs of psychological distress:

- Anxiety

- Confusion

- Feeling isolated

- Shame

- Feelings of guilt

- Passivity

- Desperation

- Self-condemnation

- Feeling demoralized

- Feelings of betrayal

Remember that in-depth stories are marathons, not sprints, Dr. McMahon said. Journalists need to pace themselves, vary their schedule and the content of their work, and make time for joy and laughter. Some helpful responses after reporting on a traumatic story include meditation, a session with a therapist, or exercise, according to the Dart Center.

Surviving Psychological Trauma

- Do not rush to transcribe the interview immediately; put the traumatic material to one side if you can.

- Vary your story angles, including stories of resilience and creative coping strategies, and provide context that includes death rates but also recovery numbers.

- Return to your plan for rest and do something to switch off, like walking your dog, sports, meditation, or just having dinner with friends or colleagues.

- Discuss any issues that arise with your colleagues. Social support is important. Help each other — find a person in the newsroom with whom you can share your experiences and look for solutions.

- Support your colleagues if they have worked on a difficult story.

- Take time to think over your response: why it impacted you and what you can do to cope.

“It’s really important to understand the nature of sustained stress,” Shapiro said. “If stress is unrelenting and protracted, eventually your performance falls off and you burn out. It’s important to take proactive steps to get our bodies and minds away from stress.”

Journalists are resilient people, but we are only human, Shapiro added. “Take the time our brains need to recover.”

Olga Simanovych is GIJN’s Russian-language editor. She has worked as a screenwriter, media trainer, managing editor, TV news reporter for Vikna-Novyny on STB, and has participated in SCOOP‘s international investigations. She is fluent in Ukrainian, Russian, English, and Greek.

Olga Simanovych is GIJN’s Russian-language editor. She has worked as a screenwriter, media trainer, managing editor, TV news reporter for Vikna-Novyny on STB, and has participated in SCOOP‘s international investigations. She is fluent in Ukrainian, Russian, English, and Greek.