How China’s Top Investigative Newsroom Digs for Data

Editor’s Note: Caixin.com is widely regarded as one of the pioneers of modern Chinese investigative journalism. From its base in Beijing, the business and financial news group has pushed the boundaries in China, breaking taboo stories and using investigative techniques to expose corrupt practices, shady business deals, and abuses of power. GIJN asked Caixin’s data editor, Huang Chen, to share her team ‘s approach to doing data journalism in a society known for the tight control of information. Her story may surprise Western journalists.

Caixin.com has delved into data journalism since mid-2013. Over this time we have produced a body of representative work and earned a wealth of experience. If you want to do data journalism, we learned, you need to start with the data.

How do we handle searches and data? Let me share with you some of our experience.

Consider the work of Yu Ning, a Caixin investigative journalist, in tracing and checking clues about people, companies, places and times in stories about people or corporations. Ms. Yu is a leading writer on finance and economics at Caixin Weekly.

The National Enterprise Credit Information Public System is an important starting point for searching company information, Yu explains. The site leads to data sites in 31 provinces and cities across the country with local company records. Among those, Shenzhen and Beijing have effective search functions.

Yu Ning cites as an example Caixin’s work on Zhou Yongkang. [In 2015, Zhou, once one of the most powerful figures in China, became the highest-ranking Chinese Communist Party leader convicted on corruption charges.]

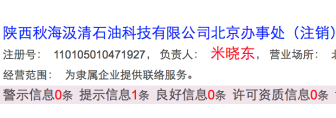

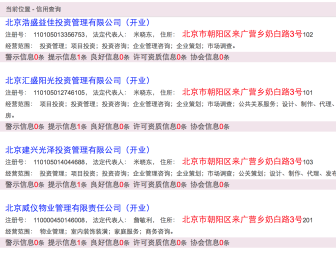

In Caixin’s story White Glove” Mi Xiaodong, Yu Ning used online searching to track Zhou’s assets and connections. While checking the Beijing Enterprise Credit Information Public System, she found a series of companies associated with Mi Xiaodong [an old friend and partner for Mr. Zhou’s son] including Shaanxi Qiuhaijiqing Petroleum Technology. This led to other figures, companies, and owners.

During the reporting, we continued to search for key persons’ names and other details. We identified and did conferences and other events they attended and did new searches on them. One search led to records of activity in Canada by Jia Xiaoxia, Zhou’s sister-in-law. Similar methods were applied to reporting on Ding Shumiao, the key figure in another corruption case involving former Ministry of Railways head Liu Zhijun.

In addition to these online searches, when companies are listed Caixin usually searches corporate financial reports, changes in shareholding, and big events through financial data terminals such as Wind. If the company is not listed, such information is less likely to be available, but there are several under-explored databases in the Wind Terminal — a Mergers and Acquisitions Database, the China PEVC Database, and the China Enterprises’ Database — through which we can obtain further information. But as the data are neither complete nor stable, we can only use it for reference.

Data Journalism in China

In doing data journalism stories, Caixin first considers the availability of data and later the news value. We usually unveil an article in the following order: data, story, visualization. We do this because it is difficult to decide on a story and find data, as data openness in China falls far below global levels.

Among all the open data sources, official websites are undoubtedly the most trustworthy. (Manipulation of raw data is another area to discuss.)

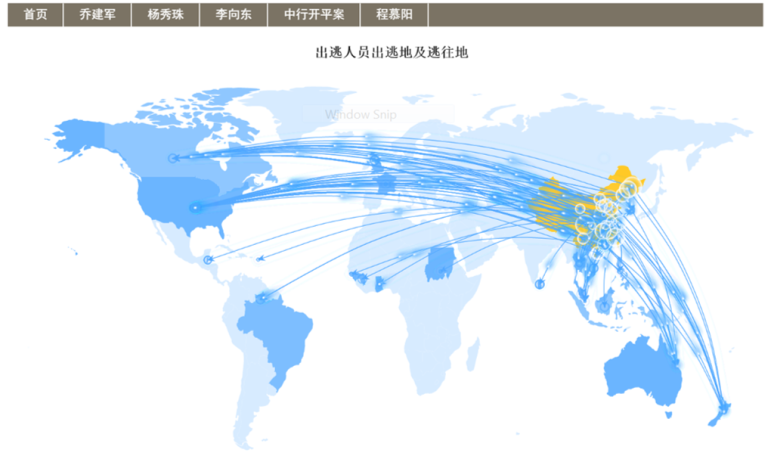

Here are some examples from Caixin’s past work. Data in the story Billboard of Sangong Expenditure (Three Public Expenses) were gathered from over 90 official websites. The story One in a Hundred Years’ Nobel Prize came from the official website of the Nobel Prize. And data for our stories The Storm of Inspection by the CPC’s Central Disciplinary Committee and Red Arrest Warrant originally came from the CPC Central Disciplinary Committee’s official website.

It is worth noting that data released on Chinese government websites is far from being standardized, so in this sense data collection is rather difficult. The lack of standardization is reflected in several ways, such as varied formats and locations. Some departments present data in a “Top News” section, some under “Notices,” and others under “Open Government Affairs.” In these cases, we must conduct searches on the site, but the findings can vary. The researchers need to be acquainted with the topic and try various keywords.

Messy formats are another example of the government’s inconsistent display of data. We have seen data published as text, PDF, Excel, DOC, and JPG, so great care must be taken to unify the data format.

Foreign organizations’ open information and sense of displaying data is more advanced than that of China. The United Nations, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), World Bank, and World Health Organization provide handy and comprehensive data sources for downloading.

We can also use Data Terminal (DT) as a reliable data source. Data Terminal is PC software provided by professional data service companies. Wind is frequently used within China, while foreign companies favor Bloomberg. Caixin uses a Wind Financial Terminal to collect data for most topics on macroeconomics and financial markets. Although the data is second-sourced, it comes from a professional data company drawing it directly from official organizations and inputing it electronically, not by hand, into their system.

Compared to gaining data directly from official organizations, Data Terminal is superior for bulk data export and data formats, so we frequently use it in our work. We also exploit information from media sources, but their reliability should be taken into account. State media like the Xinhua news agency and People’s Daily are credible in representing the official viewpoint, and local media have unique advantages. For instance, local state-run media are better at reporting last year’s economic situation and next year’s development objectives because the relevant data will have been disclosed to local officials (although these may get reported somewhat belatedly). We do not recommend using bulk data from other media outlets, as the integrity of their data is difficult to know. However, you can use it as a clue to find the primary-sourced data.

Other data sources in China include respected consulting firms, research companies, accounting firms, universities and research institutions. We need to pay special attention to several things: First, the authority of the institution we choose — it should be credible, as should the collection of every bit of data, especially the investigative data. Keep a close eye on how many samples are surveyed, whether samples match the features of the whole, how the samples are investigated, and and how the data are explained. You should be rigorous in checking these. One reason why public polling by the U.S. Pew Research Center often arouses controversy is that the samples are not representative enough.

One activity in data journalism is data mining, which can demonstrate an undiscovered or unproved trend through visualization. Sometimes this can suggest the results of an investigation early on, but we need to go back to find supporting evidence.

At Caixin, we have found that good data should be continuous, complete, and in a unified format. One needs a sufficient amount of data before drawing any conclusions. If the data are insufficient, then it is perhaps only suited for regular reporting, not the precision of data journalism.

This story originally appeared on GIJN’s Chinese-language website, http://cn.gijn.org, as 财新经验:做新闻,如何搞定搜索与数据.

Huang Chen is data editor at Caixin Media, based in Beijing. She joined Caixin in early 2010 and worked on database products and later Data News, its data journalism column. Since October 2013 she has edited projects at Caixin’s Data Visualization Lab. Prior to Caixin, Huang Chen worked on databases at financial news portals in China. She has a bachelor’s degree in engineering and a master’s degree in economics.

Huang Chen is data editor at Caixin Media, based in Beijing. She joined Caixin in early 2010 and worked on database products and later Data News, its data journalism column. Since October 2013 she has edited projects at Caixin’s Data Visualization Lab. Prior to Caixin, Huang Chen worked on databases at financial news portals in China. She has a bachelor’s degree in engineering and a master’s degree in economics.