Editor’s Note: Ahead of the 14th Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Malaysia, GIJN is publishing a series of short interviews with a globally representative sample of conference speakers. These are among the more than 300 leading journalists and editors who will be sharing practical investigative tools and insights at the event.

Helena Bengtsson is the data journalism editor at Gota Media and Bonnier News Local in Sweden, and the former data projects editor of the Guardian in the UK. She was a pioneer of computer-assisted reporting in Sweden.

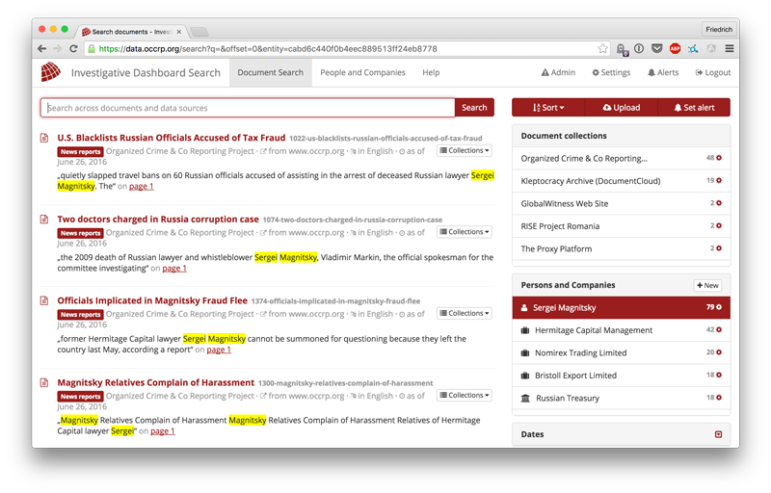

In addition to her investigative contributions to international collaborative projects such as The Panama Papers, Bengtsson has emerged as a leading global advocate for the illuminating power of data journalism, and has guided numerous reporters away from their needless dread of numbers and spreadsheets.

As she told GIJN in a prior interview: “If your editor asks you to do a story about the pension system, you just have to find the information… To be honest, data journalism is a lot easier to understand than the pension system. Every journalist should have basic knowledge of how to sort and filter a spreadsheet and do simple calculations.”

She also trains journalists in building databases with advanced digital tools, and champions collaboration. Twice a recipient of Sweden’s Stora Journalistpriset (Great Journalism Award), Bengtsson’s investigations have featured scoops with direct accountability impact, including an exposé about the impunity enjoyed by teachers implicated in sexual harassment, which triggered a new Swedish law to protect children.

In addition to sharing key data techniques in a practical GIJC25 session on Using Data for Local Investigations, Bengtsson will also lead a workshop in Kuala Lumpur called The Coding Mindset, which is designed to teach attendees how to think strategically about programming, and how to turn raw data into compelling stories.

“There are a lot of people today wanting to get into code, and they say, ‘I have to learn Python,’ and I say, ‘But do you know spreadsheets?’— and they often say ‘no,’” she explains. “We have to talk about structured data before the next steps. So that [Coding Mindset] session will be a way to give people the knowledge and the thought process, and also the thesaurus of how you should express yourself in these projects. Because even if you’re going to ask Claude or ChatGPT to program for you, you have to know when to ask for a loop or a variable.”

GIJN: Of all the investigations you or your team have worked on, which has been your favorite, and why?

Helena Bengtsson: It’s almost impossible to choose, as my current project is almost always my favorite. If I have to pick, I’ll mention two. One older project involved convincing the Swedish Statistical Agency to cross-match the database of teachers with another one of people convicted in court. We only received statistical data, of course, but by combining those numbers with case studies from around Sweden, we could show that many teachers who had been convicted of sexual harassment or even abuse were still working in schools. The story led to a change in Swedish law, allowing schools to conduct background checks before hiring.

A more recent project involved processing a huge amount of data from the Swedish Roads and Vehicle Agency, analyzing roads all over Sweden. The project identified almost 16,000 dangerously constructed curves, and we told stories from across the country about hazardous roads and accidents that had occurred there.

GIJN: What are the biggest challenges for investigative reporting in your country?

HB: Some might say that working as a journalist in Sweden is easy — we have one of the best open records laws in the world. However, this also means that many Swedish journalists are not skilled at cultivating sources; it’s not part of our tradition. Open records only get you so far. To do truly great investigations, you need to uncover the hidden information, and that usually comes from sources.

GIJN: What reporting tools, databases, or techniques have you found surprisingly useful in your investigations?

HB: My most important tool is the spreadsheet: I can’t really do anything without Excel or Google Sheets. But something that has surprised me is how helpful it can be to write down your methodology during a project, not just at the end. Describing and thinking through your process as you go allows you to discover gaps in your research and forces you to consider steps and structure. For me, this has saved me from making mistakes and helped me find things I had forgotten or overlooked.

GIJN: What’s the best advice you’ve received from a peer or journalism conference — and what words of advice would you give an aspiring investigative journalist?

HB: Many years ago, I received a grant to do a fellowship abroad. I chose to work with data journalism at the Center for Public Integrity in Washington, DC. I learned so much there, but one thing that stayed with me was the importance of tackling large datasets. They went through millions of records on contributions and lobbying, and I learned not to shy away from huge amounts of data. Nowadays, we have much better tools, of course, but one piece of advice I would give to a young investigative or data journalist is not to be afraid of large volumes of information. There are ways to process and analyze them — and if you keep your focus on finding stories, you’ll be fine.

GIJN: What topic blindspots or undercovered areas do you see in your region? And which of these are ripe for new investigation?

HB: One downside of having great access to public information is that we’re not as skilled at investigating corporations and other entities where there is no public access. I would love to do more stories about how corporations might exploit their employees or the environment. Also, as a data journalist, I also see opportunities to use various AI tools to analyze unstructured data in a more sophisticated way. It won’t be easy, and I’m still struggling to find the best tools for this, but I believe that in a few years we will be telling different kinds of stories than we do today.

GIJN: Can you share a notable mistake you’ve made in an investigation, or a regret, and share what lessons you took away?

HB: It’s always hard to share mistakes, but many years ago we did an investigation into a charity that collected a lot of money. Among other things, we found that the founders had transferred some of the money into accounts in Switzerland. One of the founders lived abroad, and there were no images of him available. Since this was for television, we needed footage. He had a very unusual name, and after a lot of research I found some old video in my network’s own archive. Because the name was so unusual and the person in the old video had the same occupation as our subject, we used that footage. But it wasn’t him — the man in the old video still lived in Sweden, and he was understandably very upset that we had used his image. He received a public apology and some compensation. I was young and new as a journalist when this happened, but I still feel awful when I think about it. This taught me to check, double-check, and then check again — and never, ever assume anything.

GIJN: Can you share what you are looking forward to GIJC25 in Malaysia, whether in terms of networking or learning about an emerging reporting challenge or approach?

HB: As always, I look forward to being humbled. There are so many amazing journalists from countries all over the world and meeting them always leaves me feeling inspired. The circumstances they work under are very different from the comfortable journalistic life I lead. I have no death threats, my phone is not tapped, I can request a lot of public information, and officials are usually (though not always) available for interviews.

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s global reporter and impact editor. A former chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world, and has also served as an assignments editor for newsrooms in the UK, US, and Africa.

Rowan Philp is GIJN’s global reporter and impact editor. A former chief reporter for South Africa’s Sunday Times, he has reported on news, politics, corruption, and conflict from more than two dozen countries around the world, and has also served as an assignments editor for newsrooms in the UK, US, and Africa.