GIJN Toolbox: CrowdTangle, Echosec, and Searching Social Media

Image: Pexels

Welcome to The GIJN Toolbox, in which we survey the latest tips and tools for investigative journalists. In this edition, we’ll explore different tools reporters can use to find user-generated content (UGC), which is any type of content — such as video or photos — that users post to social media. We’ll walk through how to use CrowdTangle and Echosec to find content on sites like Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit. We’ll also describe other tools reporters can use to dredge up Facebook content, even though Facebook, which disabled graph search in June 2019, has made it tougher for investigators to find what they’re looking for.

CrowdTangle: Finding Historical UGC Records

Let’s first take a look at a tool that journalists can use to find popular content on social media. Reporters looking for widely disseminated content to research disinformation campaigns on Facebook, for example, might want to look at BuzzSumo or the Facebook-owned CrowdTangle. These tools allow users to see some of the most shared and engaged content across social networks, and to view detailed sharing data to help identify connected Facebook pages, Twitter accounts, and more.

Let’s dive into CrowdTangle, “a public insights tool from Facebook that makes it easy to follow, analyze, and report on what’s happening with public content on social media.” CrowdTangle has a free Google Chrome extension that is publicly available but has limited functionality. The centerpiece of CrowdTangle is a platform that offers users the ability to query a database that contains Facebook public pages, groups, and public Instagram accounts. It’s difficult to get access if you don’t already have it — the site warns that the team is “only able to onboard a limited number of new partners.” But for those who already have access, or those who want to learn more about how the tool works, let’s go through the basics of the platform, and how to use it to search for UGC.

First, it’s important to note that not all public entities in Facebook and Instagram are necessarily on the platform. The tool automatically adds public Facebook pages and groups with 100,000 or more likes, followers, or members — except US-based public groups, which are only required to have 2,000 members to be added automatically, according to Naomi Shiffman, academics and researchers lead at CrowdTangle. The platform automatically adds all public Instagram accounts with 75,000 or more followers, and all verified Facebook and Instagram public profiles. However, users can manually add any public Facebook page or group, as well as any Instagram account with any amount of likes, followers, or members.

CrowdTangle can also search Reddit and Twitter, but rather than use CrowdTangle for that purpose, I prefer to use Echosec or, even better, open source coding tools like TWINT or the rtweet package for RStudio. Why? Because you know you’re getting raw data that isn’t filtered by a commercial third-party. (For a tutorial on how to use rtweet to scrape Twitter data, see this workshop by Michael W. Kearney of the University of Missouri.)

Now that we know what CrowdTangle is, let’s explore how to use it.

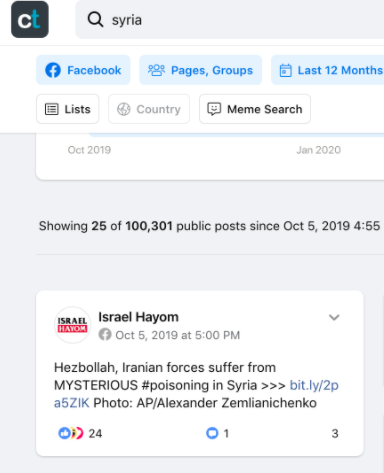

Let’s say I’m interested specifically in UGC posted on Facebook pages or groups within the last 12 months about Syria. We can do that:

Image: CrowdTangle

But let’s say I’m interested in figuring out when this specific piece of content was first posted to Facebook. I might be interested in finding out who was the original author, and who decided to disseminate it next. We can start by looking at historical data for a piece of UGC.

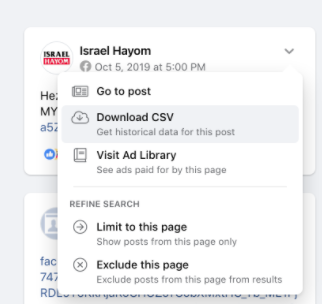

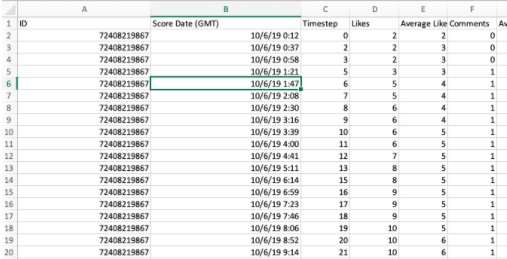

You can download historical data for a post to a .csv file: To download the file, click the drop-down arrow in the top right corner of the post box on CrowdTangle and select “Download CSV.”

Image: CrowdTangle

You can then use this information to determine all the instances where CrowdTangle picked up this particular piece of content.

It’s important to note that the historical data will only start from when CrowdTangle first entered the post into its database, not the first time the post appeared on Facebook.

This might be useful in helping to determine the provenance of a piece of content. (Provenance refers to the first appearance of a piece of content online.) A word of caution: CrowdTangle can’t tell you definitively where a piece of UGC came from, but it can lead you in the right direction to ascertain its provenance, as well as give you good information on how it began to spread on social media.

Further reporting might be able to determine where a specific piece of content came from. (Other tools you can use to investigate this include the free and open source tools which we’ll describe below and Hoaxy, which Canadian journalist and misinformation specialist Craig Silverman described in a story for GIJN.)

Finding Buried UGC on Facebook

For some investigations, journalists aren’t trying to find popular content that has been shared widely. They may be looking, in fact, for the opposite: content buried in social media platforms and forgotten, waiting to be discovered for use in accountability investigations.

For example, if journalists were trying to verify an airstrike in a foreign conflict, they might want to find pieces of UGC that weren’t widely shared or viewed. In this case, tools like CrowdTangle won’t be much help, since we’re not looking for content with high engagement. In the past, when searching for specific Facebook content, you could have used graph search-based tools — such as Who Posted What?, graph.tips, or Intelligence X’s Facebook Graph Searcher — which manipulated Facebook’s URL structure to find content that matches specific parameters.

Much to the chagrin of investigators, however, Facebook blocked access to its graph search in 2019, rendering many previous search functions inoperable. But we can still put together a search. We recommend using the tools described below as a jumping-off point, then using the native Facebook search platform — or Google dorking, which we describe below — to continue the hunt. Keep in mind that Facebook’s search platform is far from perfect; it will not necessarily show every result in your search criteria. This makes it exceedingly difficult to find the data you’re searching for when investigating a specific incident or individual.

In the old Facebook URL structure, you could craft an entire specific search just using graph search. No more. You’ll have to dig a bit harder to find what you are looking for. It’s also important to note that Facebook’s algorithm will prioritize results that it thinks you’re looking for, so keep in mind that you might have to keep scrolling and trying different search combinations to ultimately find content relevant to your investigation.

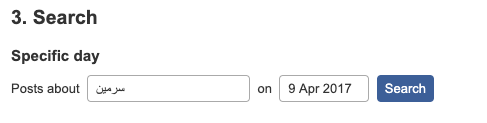

Who Posted What? is a free tool that lets users find a Facebook ID number, which you can then use to search on graph.tips for posts and photos from a specific user. Who Posted What? also allows users to search for posts about specific keywords on a certain day, month, or year. Say, for example, I’m trying to find information about an airstrike in Sarmin, Idlib Governorate, Syria, on April 9, 2017. I will take the Arabic word for the town in which the airstrike occurred and put it into Who Posted What?, searching for this keyword on the date of the strike.

Here’s what Facebook comes back with. I was able to find a few posts that might be relevant to my query (circled in red) pending further verification:

Although Facebook has reduced search capability via graph search, there are still ways to find the UGC you’re looking for, either through openly available tools, like the tools listed above and Loránd Bodó’s custom social media search engine, or through paywalled tools, like Echosec, X1 Social Discovery, and Samdesk, although these can be cost-prohibitive.

Image: Whopostedwhat.com

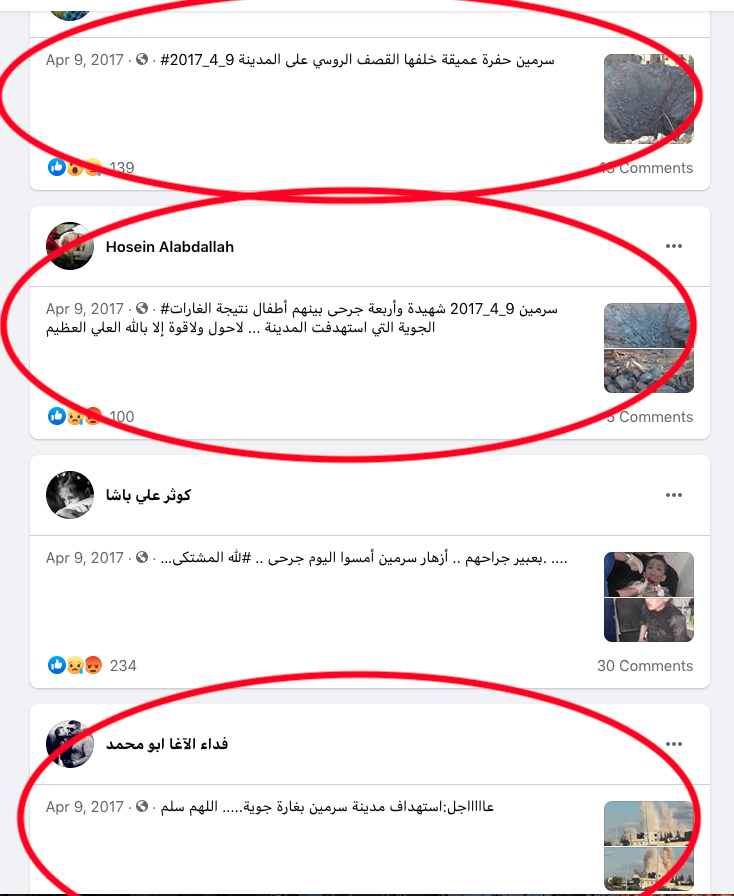

Another tip is to use advanced Google searching — sometimes called Google dorking. Google dorking has been covered extensively — both on GIJN’s site and elsewhere — so we won’t go into detail here. But using Google to search for Facebook content can be more effective than using the Facebook’s native search.

Here’s a quick example of a Google dork that I did searching for posts on Facebook relating to August 2020 protests in Kenosha, Wisconsin. Here’s my search query:

site:facebook.com protest AND kenosha -news

The operator site:facebook.com narrows the search to just Facebook. My keywords of protest AND kenosha ensure that both words are present in the post text, and -news excludes the word news from the post text. I wanted to exclude posts from news organizations because I just wanted to see original posts from ordinary citizens on the ground, not other journalists. I still got some news organizations that returned in my search results, but I was able to filter out a lot of the posts I did not want.

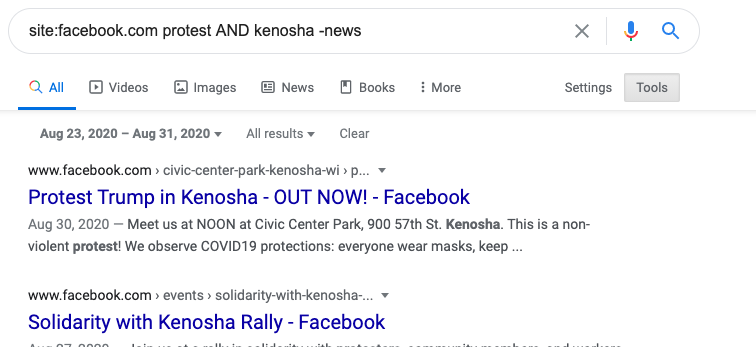

Notice that I also limited the search by date. I just wanted content posted in the month of August, starting with the day of the inciting event and going through the end of the month. You can create a date filter by clicking “Tools” and selecting the “Any time” dropdown menu. Then click “Custom range….” and set your start and end dates.

Echosec: A Powerful Platform for Finding UGC

Echosec is a paid tool that pulls from social media sites like Twitter, YouTube, Reddit, Medium, Gab, Discord, 4chan, and the Russian social media sites VK (VKontakte) and OK (Odnoklassniki), among others. Defining a geographical area of interest (AOI) allows you to search for posts that were geotagged within a certain defined area. Users can virtually draw their own AOIs onto the map using a mouse or enter a location by typing it into the search box.

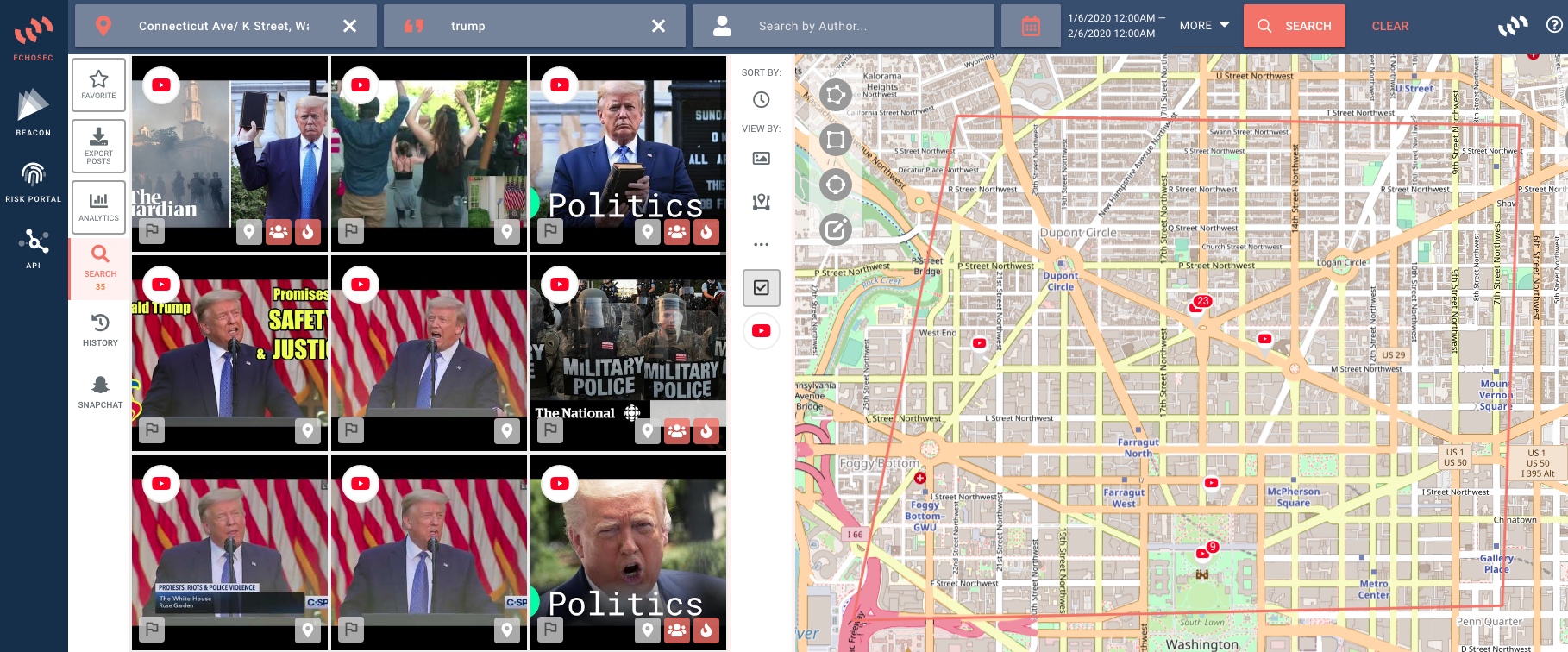

Say I’m interested in finding videos related to the June 1 incident in Washington, DC, in which protesters were tear-gassed in the plaza between St. John’s Church and Lafayette Square in order to allow US President Donald Trump to move through the area and take a photo.

I draw a rough AOI around the area that I’m interested in, then add the keyword “Trump” and add a time filter because I only want posts from June 1 or later. Here’s what Echosec finds:

Image: Echosec

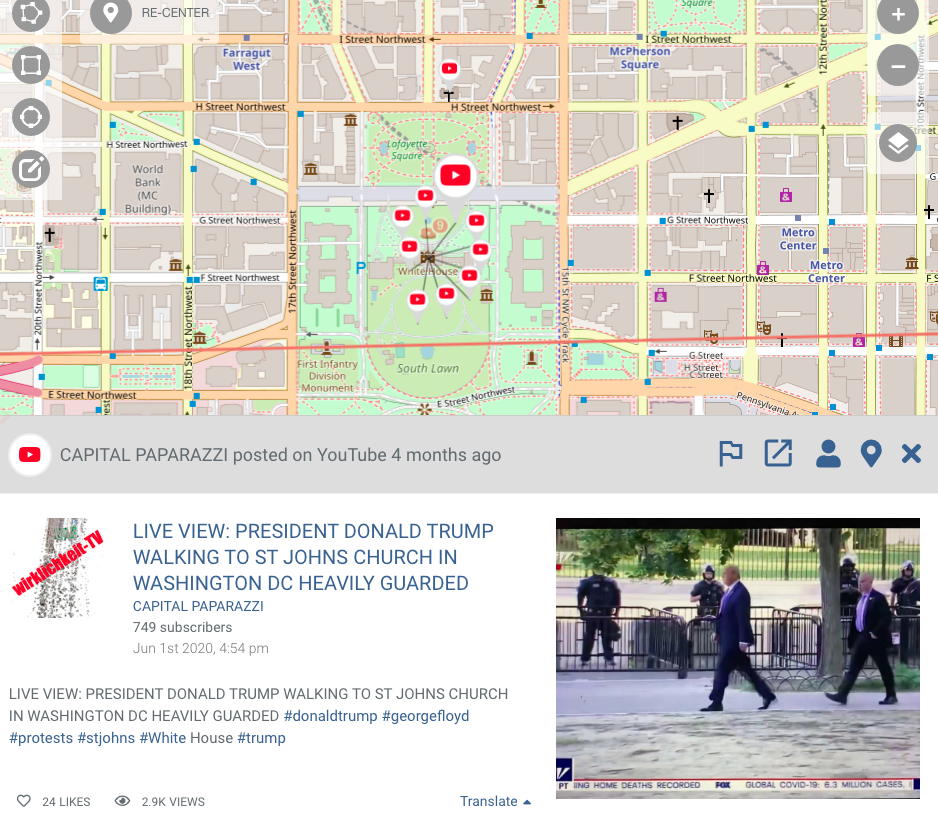

Turns out there are a lot of results. Let’s drill down into the specific area around Lafayette Square. Looks like there are at least 10 different YouTube videos that Echosec found in the area.

Image: Echosec

Here’s an example of one of the videos Echosec found:

Image: Echosec

Reporters could use this tool to find content, such as videos or photos, that they can then geolocate and chronolocate — that is, locate the video in space and time, respectively — in order to verify if the video was actually shot at the stated place and time. This is one of the first steps to verifying a photo or video posted online. For more training on how to verify UGC, see these basic and advanced training courses from First Draft, which is a nonprofit organization battling mis- and disinformation.

The pricing model for access to the Echosec Systems Platform is highly dependent on factors that can only be determined on a client-by-client basis. Echosec Systems has worked with journalism organizations, such as GIJN member Bellingcat, in the past; journalists are invited to book a demo call with the Echosec sales team here. Additionally, subscribers get access to the Echosec Essentials training course free of charge.

That’s all for this edition of The Toolbox. Coming soon: using remote sensing data from NASA for verification, finding identical usernames across social media, facial recognition software, and a new tool from the Google News Initiative called Pinpoint.

Recommended Links

- Social media timestamps infographic from First Draft

- Mining the Social Web: Data Mining Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, Instagram, GitHub, and More, 3rd Edition (available for purchase on Amazon)

- Social Media Search Strategies from Loránd Bodó’s blog

Additional Reading

My Favorite Tools: Malachy Browne

GIJN’s Resource Center: Fact-Checking & Verification

Online Investigative Techniques — GIJN Webinars and Workshops with Henk van Ess

Brian Perlman is an assistant editor at GIJN. He specializes in human rights violations research using advanced digital forensics, data science, and open source techniques. He is a graduate of the UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism and a former manager at the Human Rights Center at Berkeley Law.