The archive session at GIJC25, with Jennifer LaFleur (left), Juliana Dal Piva (center), and Hadi al Khatib (right). Image: Alyaa Alhadjri for GIJN

Archives offer journalists new muckraking avenues and stories, from revealing how the US government broke promises made to freed slaves in the 19th century to uncovering crimes against humanity in Syria and Brazil.

During the “Digging into Archives — Historical Investigations” panel at the 14th Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Kuala Lumpur, Juliana Dal Piva, columnist and investigative reporter from the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (CLIP) and ICL Noticias, Hadi al Khatib, managing director of Mnemonic, Jennifer LaFleur, data journalism professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and moderator Tristan Ahtone, editor-at-large of Grist, shared how to create and use archives to strengthen journalistic research and legal accountability by wrongdoers.

An Archive Origin Story to Document War Crimes

When describing Mnemonic, a digital archive created to investigate international crimes, Hadi al-Khatib explained some of the decisions archivists make.

“We started this work ten years ago because most of the information we collected was posted on social media platforms, and it was being erased because of the algorithms these platforms used,” he said, highlighting how vital information, such as proof of attacks on hospitals during the Syrian civil war, needed to be saved.

Clips that proved international crimes were committed were being deleted by platforms such as YouTube for its “graphic or explicit content” to comply with the algorithm’s standards. Thanks to its team and sources, Mnemonic has archived more than 30 million records and 400 terabytes of information from over 100,000 sources.

As both an online archive and an investigative team, Mnemonic conducts essential work to find out what happened to people disappeared by the authorities after being detained in checkpoints and roadblocks set up by the Syrian army during the early years of the war.

Everything stored in the archive aims to meet the extremely high bar that courts demand for accepting videos, photographs, recordings, and documents that aren’t original. They’ve also designed software to prove that these items haven’t been altered. Mnemonic archivists also transcribe audio from video using machine learning software to enable keyword searches.

Some lessons learned from Mnemonic’s work are:

- Make sure your archive is set up so the material in it survives, even if it’s deleted from all other internet sites and platforms.

- Use software that verifies your archival material hasn’t been tampered with when copied and stored, so it’s useful to journalists and legal authorities.

- Allow word searches for PDF file content, and transcribe your archive’s audios and videos so users can also search for keywords.

- Be mindful of using software that properly blurs graphic content in your material which will only be unblurred if the researcher goes through extra steps that verify its intended use.

- Have strict, clear, and public policies and methodologies for your archives on issues such as data sharing and verification — to allow for collaboration with institutions that have high security or reliability standards.

Building Stories from Archives

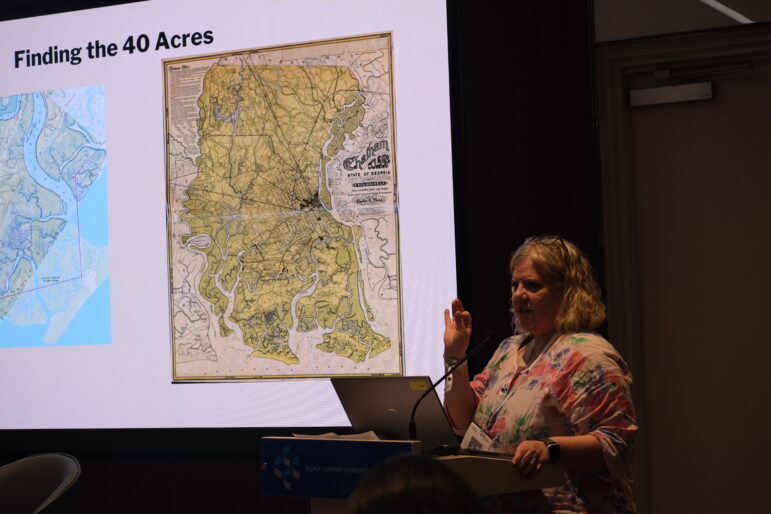

Jennifer LaFleur explains how they scoured the archives for material for their investigation into historic injustices and slavery. Image: Alyaa Alhadjri for GIJN

Ultimately, an archive’s potential is realized when a researcher uses it to tell a story that uncovers wrongdoing relevant to present-day readers or viewers. LaFleur and her team from the Center for Public Integrity and Reveal proved in the “40 Acres and a Lie” podcast and multimedia platform that, after slavery was abolished in the United States, the federal government rescinded a Special Field Order from 1865 to give each freed slave family up to 40 acres of confiscated land.

This act set off a chain of injustice against African Americans linked to contemporary structural inequalities and racism that was laid bare when the researchers interviewed the descendants of African Americans who received land that was later taken away.

“We spent a lot of time in archives and museums and historical centres trying to get records to fill in all the blanks,” said La Fleur. She added that her team also built a tool to enable other researchers to search documents in one of their main sources, the Freedmen’s Bureau — established by US Congress in the 19th century to help former slaves transition to freedom and which contains names and information for hundreds of thousands of people.

Dal Piva, in her book “Crime Without Punishment: How the Military Killed Rubens Paiva,” examines how Brazilian congressman Ruben Paiva — who in 1971 was taken by armed men who claimed to be members of the Brazilian Armed Forces — was murdered by a former military member, and details what happened to him while he was “disappeared.”

Paiva’s kidnapping, torture, and killing are painstakingly described — illuminating aspects of a past with which Brazil hasn’t fully grappled. “There’s so much about the dictatorship that hasn’t been done,” said Dal Piva. “It’s even difficult for us to do stories on this, because there’s a culture of silence.”

Both investigators highlighted how they approached the archives to tell a story. La Fleur’s team grounded the archive’s findings in storytelling by later finding and interviewing the descendants of former slaves. Dal Piva — who used judicial archives and court records to help uncover what happened to congressman Paiva — tapped into storytelling techniques to narrate the twists, turns, and surprises that come up when uncovering new documents in an archive.

The main tips they shared to approach archival research are:

- Ask yourself who set up the archive and to what end? How is the archive structured, and where in it will the information you need most likely be?

- Find someone familiar with the archive who might initially guide you, such as archival staff and academic researchers.

- Don’t be afraid to change course. Keeping with the same metaphor, listen to the archive as you’d listen to a friend, and tell the story without imposing your biases or preconceptions, even if that takes you in new directions.

- Collaborate with other journalists and organizations. Archives can be overwhelming, so don’t take it all on yourself.

Dal Piva suggested getting to know the archive almost like you would a friend. Indeed, more than a passive information vault, archives are architectures of information moulded by people and institutions through choices. Be familiar with them and also let them surprise you: They might hold the key to stories others gave up on uncovering long ago.