Journalists shared how they overcame challenges to reporting on water scarcity, such as lack of transparency and access, at the 14th Global Investigative Journalism Conference in Kuala Lumpur. Image: Suzanne Lee, Alt Studio for GIJN.

Human demand for fresh water is depleting rivers, aquifers, and reservoirs far faster than natural systems can replenish them.

Cape Town, Beijing, Tehran, Los Angeles, and many other cities have had supply crises in the 2020s and face water scarcity in the future. According to a recent UN report, half the world’s population faces severe water scarcity at least one month per year, and the situation is deteriorating.

In countries such as Argentina, Jordan, and Egypt, intensive mining and agricultural projects are devastating water sources. Journalists and editors covering water scarcity issues in these countries discussed their methods and strategies at the 14th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (GIJC25) in the session “Investigating the Water Crisis Through a Local Lens.”

The panel included Edgardo Litvinoff, co-founder and editorial director of Argentina’s investigative outlet Ruido; Eman Mounir, an Egyptian journalist that has reported extensively in the Middle Eastern and North Africa region for outlets such as National Geographic; and Jordan’s Lina Ejeilat, executive editor of 7iber, shared a panel moderated by Andrés Bermúdez Liévano, an editor at the Latin American Center for Investigative Journalism (El CLIP).

The panelists said that while their reporting on the issue was local, they have all encountered four common obstacles in their reporting:

- Lack of transparency

- Lack of access

- Complexity of data

- Media resistance to reporting on the topic

They also noted that they have had success in overcoming these obstacles with similar practical tools — that regardless of where in the world you report on water crises, there is a roadmap to help you address these particular challenges that will also be helpful to investigative journalists who cover environmental issues generally.

Overcoming Lack of Transparency

“Water problems are never just technical,” said Ejeilat, executive editor of Amman, Jordan-based 7iber. “They’re also political and economic.”

Jordan currently has only 61 cubic meters (13,420 gallons) of renewable fresh water available per capita per year; countries with fewer than 500 cubic meters (110,000) of water per capita per year are considered to be experiencing “absolute” water scarcity — when the demand for water exceeds its water resources.

Ejeilat has covered the intersection between water, politics, and economics in Jordan, in particular its changing uses of the Disi Aquifer — shared with Saudi Arabia — which have included agriculture and supplying drinking water to the capital, Amman. Accessing public information is difficult in Jordan, where there is a gap between the relatively open access to information laws on paper and what journalists can actually obtain from FOIA requests.

“We had no access to the contracts between the government and these companies [involved in water-related projects] to know what sorts of rights and concessions they were given, what sort of privileges,” said Ejeilat.

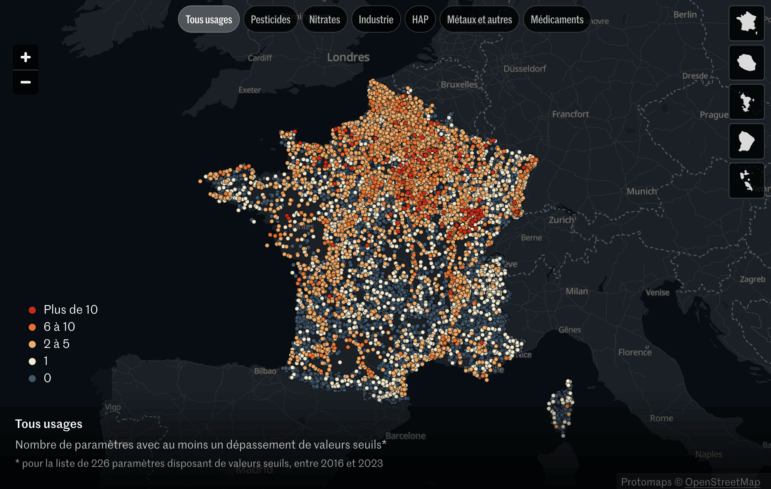

When Eman Mounir was investigating Arabian Gulf desalinization plants dumping brine back into the ocean — potentially causing hypersalinity, which harms aquatic life and public health — she also encountered a serious lack of information. “The Arabian Gulf is very closed and there is no data. Nothing at all,” said Mounir.

Ruido co-founder Litvinoff encountered the same problem when reporting on mining companies depleting rivers in Argentina’s side of the “lithium triangle” — a region shared with Bolivia and Chile where 65% of the world’s lithium is mined.

“In Argentina, the mining concessions are given by provincial governments, and they are very shady governments, very opaque governments,” he said. “It’s very hard to get public data. You can’t get concession contracts in some provinces.”

Ejeilat, Mounir, and Litvinoff were able to address the lack of data with the following methods:

- Searching for information on platforms from foreign governments or multilateral institutions with a greater degree of transparency. Ejeilat, for example, pointed out that she could find more information about the projects in Jordan through databases in the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, the United Nations Development Programme, and the US Department of Agriculture.

- Parliamentary session transcripts can be a gold mine for information such as extraction privileges and auto-renewing clauses.

- Company websites have data hidden in plain sight. Old reports and feasibility studies contain extraction assumptions and cost-benefit analyses.

- Use satellite imagery to get a Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI). This will tell you how much vegetation there is in an area and thus an estimate of how many crops there are.

- Don’t be afraid to contact private databases and try to receive their information for free as a journalist. Be tenacious. Mounir, after six weeks of negotiations, gained access to a huge GWI consumer research database free of charge through one of these companies. She added that she’d be happy to share it with any other journalists who might need it.

- When you don’t have data, you can also triangulate extraction volumes for estimates. For example, you can get an idea of how much water is being used if you know how much water the crop needs and how much is exported.

- If you’re looking for an official gazette but can’t find it or download the pdf, you might find that same information by doing a simple Google search of the contents you expect to find. And well, you might even find the gazette published in a different place this way.

Gaining Access

In Argentina, Jordan, and the Gulf States, access to mining, agricultural, and waste dump locations can be extremely difficult. Journalists were either barred from entering the sites, which were in inhospitable locations with precarious roads, or it was simply impossible to access a specific location. The reporters were able to overcome access difficulties by:

- Investing in technical resources. Litvinoff said about 25%-50% of their reporting budget went to drone video recordings over mining areas to which companies barred access.

- Mounir couldn’t take samples from the Arabian Gulf to measure salinity levels, but she found academic experts through Google Scholar who had worked on the issue and had taken samples. Although some academics did not talk to her out of concern for their safety, she was able to use their work and breach access gaps.

- Use fixers and be very patient when building trust in communities where you need testimonies and interviews. It might even take you six months to find the right person to talk to or someone who agrees to being filmed.

- Interview workers and contractors. They often have data that the company owners hide.

- Use partnerships with local media outlets and journalists to gain access to certain areas, sources, or information. Collaboration is key.

Understanding Data

All the journalists on the panel have struggled to make sense of complex technical data with which they weren’t familiar, and with taming large, raw databases. Information you’ll find while reporting water supply, mining, and agriculture —such as sample analysis, biological and chemical data, and business documents — might be overwhelming and difficult to read. This is how they tackled the issue:

- Be careful when using academic sources, because they’re also susceptible to political manipulation. Mounir said she didn’t rely on any single study and also compared and verified academic information.

- You don’t need to hire an expert to work with data. Clean and verify it using Excel, Google Sheets, and QGIS. “Start simple. Excel can take you very far. QGIS can take you the rest of the way,” said Mounir.

- Litvinoff suggested using NotebookLM to compare different sets of data and documents: “We think it’s an essential tool for every journalist,” he said. “It allowed us to quickly discover inconsistencies between the company report and the real academic studies mentioned in the company report.”

- Partnerhips. Look for people who you think might help you make sense of complex information.

Edgardo Litvinoff, co-founder of Ruido, Egyptian journalist Eman Mounir, panel moderator Andrés Bermúdez Liévano, and Lina Ejeilat, executive editor of 7iber (left to right) speaking at the Investigating Water Crisis panel at GIJC25. Image: Suzanne Lee, Alt Studio for GIJN.

Spreading the Word

Let’s say that after months or even years of research, you have findings you believe are explosive. How do you get them out there? How do you navigate efforts to silence them or the risk that the audience might not understand it, or might not even care? Litvinoff pointed out that mainstream media outlets may be compromised. They are part of large conglomerates that have vested interests in mining or extractive projects, or they depend on their advertising money.

These ideas can help you spread the word:

- Create or join a network of like-minded independent news outlets and try to publish the findings at the same time, to attract the most attention. Don’t fret about the scoop, focus on the impact.

- Work with graphic and motion designers to make this topic visually interesting and attractive. Create interactive content. This will also help people who are new to the topic make sense of it. Mounir is working on gamifying some of these findings with National Geographic to help people understand the issue.

Bear in mind that many of these tips and tools used by water reporters to overcome their challenges may be used for many other topics in environmental journalism, such as deforestation, decline in animal populations, and most forms of pollution. Go through them, take what works, and jump over your hurdles.