Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Tips for Turning Unreadable Text Into Evidence

Read this article in

You know that feeling when you’re staring at a crucial piece of evidence — a blurry license plate, a pixelated document with names you can’t make out, or a grainy screenshot where you know the information you need is right there, taunting you from behind a wall of pixels?

You don’t? Lucky you. I encounter this problem constantly in my investigations — whether it’s extracting names from footage, decoding partial numbers from social media posts, or reading distorted text in documents. While everyone else is out there living their lives, I’m playing “Guess That Pixel.” I don’t mind. The ability to transform the unreadable into readable intelligence is awesome.

Time for a manual on making blurry nonsense make sense. The tools and techniques in this article aren’t theoretical. They’re practical methods you can apply to your own difficult-to-read evidence. Because in OSINT, the difference between a dead end and a breakthrough often comes down to making those last few pixels count.

The real work happens between your ears and behind your eyes — knowing which tools to combine, how to verify outputs, and when to trust (or distrust) your results. Because at the end of the day, the difference between amateur hour and professional investigation is having a system that consistently works, even when the pixels are fighting back.

The Blurred License Plate

People in open source intelligence love their tools. Ask any specialist for recommendations and they’ll fire off names like “just use Topaz Gigapixel Pro” or “try any Gyro-based Neural Single Image Deblurring tool — here is a list of all these tools. But the real solution isn’t always in your favorite software; it’s often about admitting you don’t know everything.

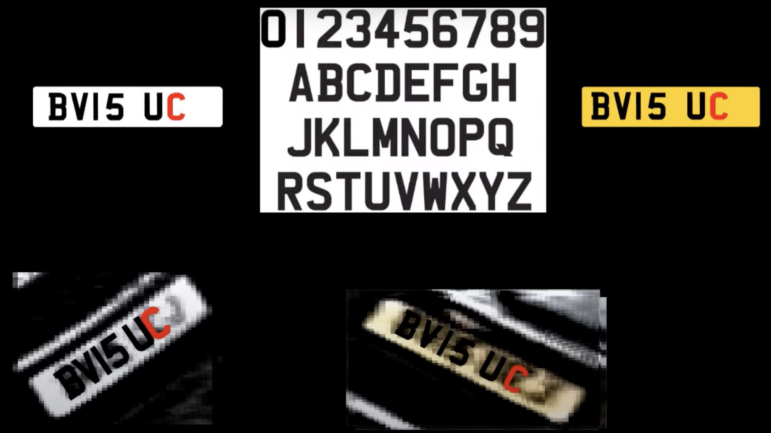

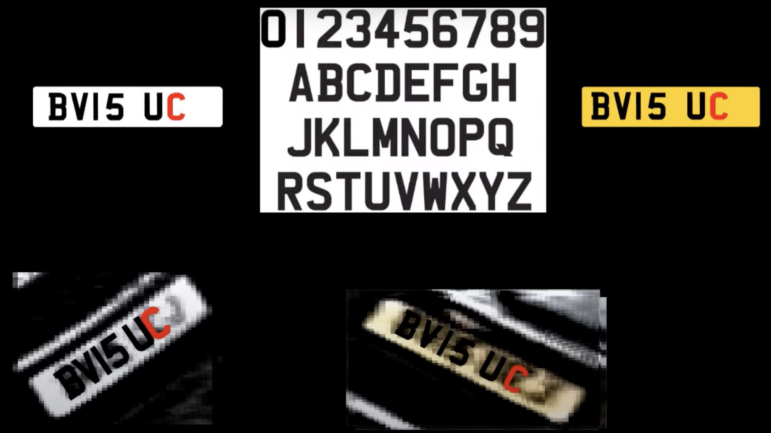

I showed this blurred license plate to 50 people from BBC Verify during a session in London. Most of them could easily name three tools that would help deblur it. But here’s the thing — they all didn’t work. What are your options now?

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

My favorite technique in 2025: I put all my failed attempts into an AI chatbot like some kind of digital therapy session — “I tried Topaz, Remini, DeblurGAN v2, ImageJ+ DeconvolutionLab2” — and then watch as it suggests “BeFunky Image Editor.” Seriously? I’d never heard of BeFunky before, but it turns out this free tool with a name that sounds like a rejected Netflix original actually worked better in this case than the $200 fancy software. It’s peak “maybe I don’t know everything” energy, and honestly, that’s when the real breakthroughs happen:

Images: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

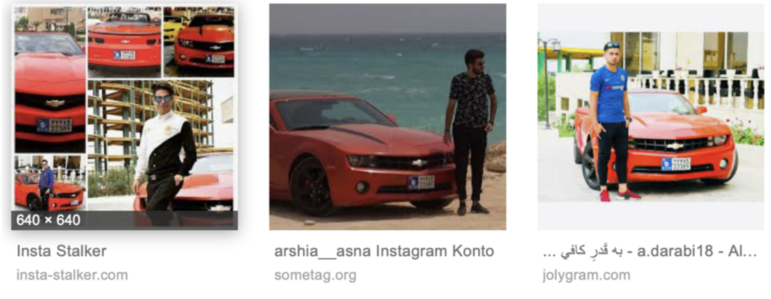

That tool never worked that well again, but hey — when I listed it among the tools I’d already tried, I got fresh suggestions. Sometimes the best advice comes from sharing your failures. When you actually can read the text, you need to find context. While researching a red Chevrolet Camaro’s license plate (used by a Dutch criminal), I didn’t have trouble reading the digits — my problem was with reverse image searching. Sometimes Google simply doesn’t recognize a cropped detail of a photo.

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

You can work around this by typing the visible text into Google Images instead of reverse searching the photo itself. This led me to images of tourists in Iran driving the same red Chevrolet Camaro with the same license plate. Ah, the criminal had rented a car (full story here).

Images: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

The Open Laptop

Here’s a pro tip that sounds almost too stupid to work: If your text isn’t completely potato-quality, just literally ask AI to transcribe it directly. No fancy tools, no image processing wizardry — just upload the thing and say: “What does this say?” My current favorite is Gemini Pro 2.5, which apparently has decided to become the world’s most overqualified proofreader.

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

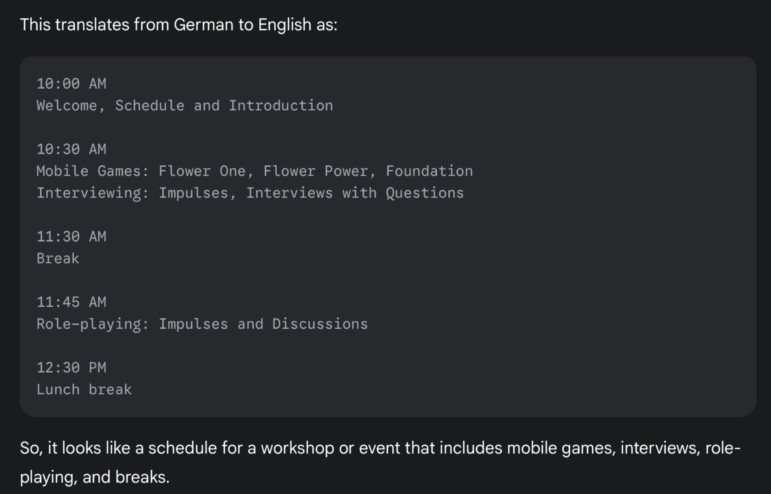

While you’re still squinting to figure out if that’s an “a” or a sad face, the chatbot has already transcribed AND translated the unreadable text for you:

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

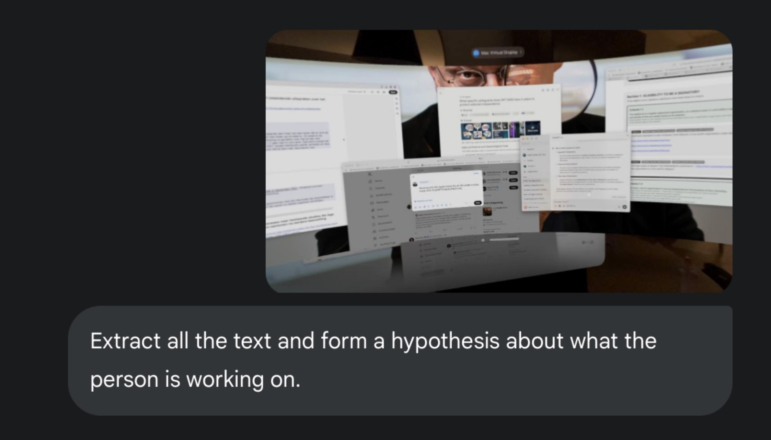

The 170 Unreadable Words

Take a look at this photo. I travel a lot, so I can’t lug monitors around with me. Instead, I use virtual reality glasses to get work done. How many words can you make out in this screenshot that I intentionally blurred as much as possible?

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

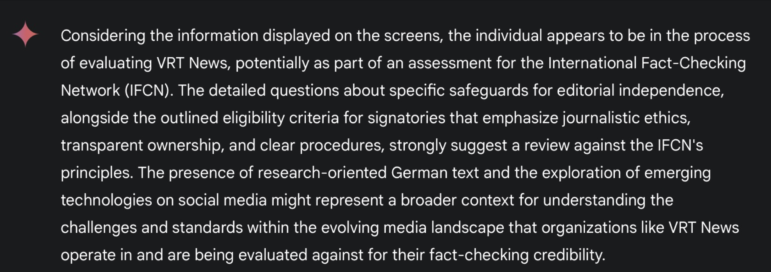

While you’re still squinting at the image, I uploaded it to Gemini 2.5 Pro. It managed to read about 170 words from the photo and gave me an accurate summary of what I was actually doing.

Images: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Geolocation with Text

I was recently working for two weeks in Berlin, and I love giving these little OSINT intro sessions to students about how terrifyingly effective investigative techniques can be. It’s educational, it’s slightly horrifying, and it definitely makes everyone immediately check their privacy settings.

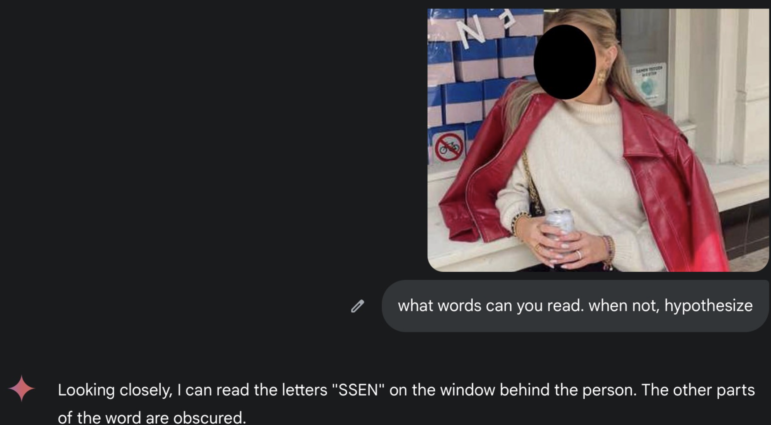

Let’s dissect this photo. The question is : Where is this, and when?

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

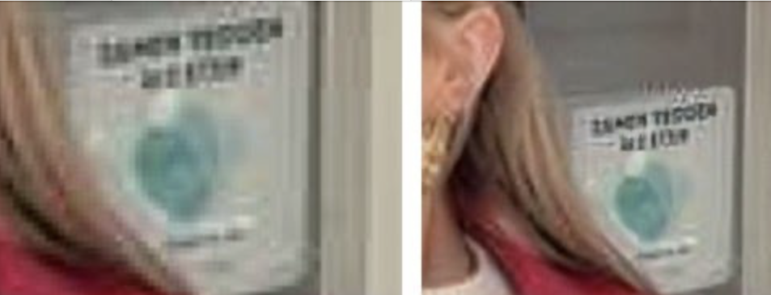

The “no bikes” sign probably rules out Malta, Cyprus, Spain, Luxembourg, and the UK and makes Netherlands, Denmark, and Finland highly likely candidates. The reason is simple: “no bikes” signs are most common in countries where cycling is actually a thing. These signs probably don’t exist where nobody bikes in the first place — they exist where so many people bike that you need to actively tell them not to park here. It’s like finding “no swimming” signs at the beach versus finding one in the middle of the Sahara Desert — one is practical public safety, the other is just a mirage. You can see text appearing twice — a word that says “essen” or ends with “Essen” — plus a greenish logo with three, four words. This time, AI doesn’t outsmart us:

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Can BeFunky come to the rescue once more? It improved the text quality enough that I could read the words “samen redden.” This means the text is in Dutch and says “samen redden [something]” — which translates to “save together [something].”

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

So what’s worth saving? It’s probably a sticker on a window of a shop or restaurant, so it probably won’t say “Save together… communism.” Maybe it says: “Save together capitalism”?

Nah, scratch that — that’s way too far-fetched. It’s probably something uplifting like “Save together… energy” or “Save together… the whales” or just “Save together… on parking.” Or maybe… wait, no, I’m doing that thing again where I overthink everything. Don’t think. Stop guessing. Start searching.

We’re pretty sure “save together” is followed by one or two more words — probably not more than seven characters if the font size matches the first line. Now here’s the fun part: how exactly do you explain this incredibly specific font-analysis-based word count estimate to Google without sounding like a conspiracy theorist who’s had way too much coffee? This is the point where normal search queries meet forensic typography (which we will discuss in part two of this article), and everyone starts questioning your life choices.

How do you tell Google that you don’t know the right words?

Replace the unknowns with a star:

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Why use quotation marks? Because without it, Google assumes you meant “samen” and “redden” anywhere will do when you really need the words together in that exact order. The quotation marks force Google to find these words as an actual phrase, not scattered across different paragraphs like linguistic confetti. And critically, when you add that asterisks at the end, you’re telling Google:

“These words definitely continue — there’s more text after this, don’t show me results where the sentence just ends here.”

It’s basically saying: “No, I really do mean these two words next to each other, AND I know there’s more coming.” Here is the result:

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

It turns out it’s “together we save food” — which is from the Too Good to Go app. Before we study that new fact, why did we use Google Images? While regular Google is trying to be all sophisticated with its natural language processing, Google Images is like “Oh, you want text in images? I’ve got millions of them, and I’ll show you exactly where these words appear together, including ones you didn’t even know existed.”

It’s the difference between asking a librarian for books about “saving food together” and asking them to show you every photo that has those exact words on it. One gives you articles and think pieces, the other shows you actual store windows and campaign posters. Like this great new tool that shows you every text in StreetView in New York:

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Back to our case. Too Good to Go is basically the dating app for vegetables and day-old pastries, where restaurants, supermarkets and cafes put up their unsold food for rescue at the last minute.

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Time to investigate those “SSEN” letters. Next stop: Claude, the semantic analyzer.

I gave it the specifics — Dutch words ending in “essen” on restaurant or shop windows — and it immediately fired back “Delicatessen.” Of course. While I’d been playing detective the actual solution was just asking an AI that specializes in language patterns.

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Sometimes the simplest approach is just admitting you need a better brain than your own, especially one that actually knows Dutch vocabulary.

I downloaded the Too Good to Go app and searched for delicatessen shops. I wasn’t impressed. Claude explained why:

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Most of the listings are in Amsterdam, so I started there. Behind the windows there appear to be white and blue boxes.

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Here’s the fun little trick nobody tells you about — if your investigation hinges on specific colors, just tack them onto the end of your Google Images search like some kind of digital afterthought.

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

It’s like adding sprinkles to your ice cream, except the sprinkles are forensic evidence and the ice cream is a Google search. Delicatessen Amsterdam white blue suddenly becomes this incredibly specific query that cuts through all the generic restaurant listings and gets you straight to the shops with those weirdly specific colored boxes in their windows. Who knew colors could be a search parameter? It’s both genius and obvious at the same time.

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Our first candidate is Flo’s Deli in Amsterdam.

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

And wouldn’t you know it, it’s a perfect match right off the bat.

What we’ve got here is basically the OSINT equivalent of winning the lottery on your first ticket. See, on the left you’ve got our starting point — some mystery person in a red jacket, sitting outside what could be literally any shop in Europe, with their face helpfully blacked out because apparently privacy still matters. All we had to work with was a “no bikes” sign and some vague color patterns that could’ve been anything from a barber pole to a really ambitious tic-tac-toe board.

The right side shows us the money shot: Flo’s Deli, complete with that “samen redden we eten” we’ve been obsessing over, the exact same blue and white striped window situation, and that “no bikes” sign sitting there like a proud little beacon saying: “Yep, this is definitely the place!”

After bouncing around between different AI analysis tools like some kind of digital pinball — with them helpfully determining that yes, this photo was probably taken in spring or fall (thanks for that groundbreaking seasonal detective work, robots) — we’re wrapping up this first installment of “Turning Unreadable Text into Evidence” with the most beautiful, time-tested classic tool in the OSINT arsenal: the Time Machine in Google Maps.

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

In May 2022, the shop wasn’t open yet. So the time frame must be somewhere between now and May 2022, right?

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Well, if you have plenty of time left — and apparently nothing better to do with your life — you can even pinpoint it to a more specific period by looking at thousands of tourists’ photos of the shop. Because obviously that’s a completely normal way to spend your afternoon.

Those white and blue boxes? They contain bagels.

Image: Courtesy of Henk van Ess

Which, in the grand scheme of investigative breakthroughs, is about as earth-shattering as discovering that ice is cold. But here’s where it gets delightfully ridiculous: by looking at other contextual photos and tracking the normal seasonal rise and fall of bagel box displays, you could actually pinpoint this photo to autumn 2024.

So what have we learned? That advanced forensic techniques sometimes mean asking an AI chatbot for help, that a $200 tool might be beaten by something called ‘BeFunky,’ and that analyzing Amsterdam bagel patterns is somehow legitimate detective work now.

But here’s the real takeaway: the secret to making unreadable text readable isn’t in any single tool. It’s about having a system — scrutinize each detail, combine multiple approaches, admit when you’re stuck, and ask for help (even from AI).

Next time: we’ll share more of Bellingcat member Timmi Allen’s techniques from our Chinese credit card investigation, including how to recover some financial insights from impossibly blurry video footage. Because apparently, that’s just a typical Sunday in the world of digital forensics.

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared in Digital Digging, Henk van Ess’s newsletter on the Substack platform. It has been lightly edited and is reprinted here with permission.

Dutch-born Henk van Ess teaches, talks, and writes about open source intelligence with the help of the web and AI. The veteran guest lecturer and trainer travels around the world doing internet research workshops. His projects include Digital Digging (AI & research), Fact-Checking the Web, Handbook Datajournalism (free download), and speaking as a social media and web research specialist.

Dutch-born Henk van Ess teaches, talks, and writes about open source intelligence with the help of the web and AI. The veteran guest lecturer and trainer travels around the world doing internet research workshops. His projects include Digital Digging (AI & research), Fact-Checking the Web, Handbook Datajournalism (free download), and speaking as a social media and web research specialist.