‘Giving Sources Power’: Reporting on Indigenous Communities and Creating Compelling Investigative Podcasts

The brutal legacy of the state’s treatment of Indigenous people in Canada is closer to the present day than many realize. Government policies and goals for eliminating Indigenous culture dating back to the 18th and 19th centuries — whether through violence, land seizures, legislation, or forced assimilation — continued by other means until the late 20th century and beyond.

Though there is some national awareness of abuse and fatalities at residential schools — the last of which closed as recently as 1997 — fewer are aware of the Sixties Scoop, referring to the era from the 1950s onwards when tens of thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their families without their consent and adopted into mainly white middle-class families throughout North America. Both policies stripped Indigenous children of their cultural heritage and isolated them from their communities.

Many contemporary issues investigative journalists cover, such as the long-term impact of this generational trauma, are rooted in state-sanctioned policies like these. Investigating their legacy requires journalistic integrity and the skill to probe deliberately opaque institutions, as well as a level of care and understanding toward sources that many outlets are often unable or unwilling to provide.

Connie Walker has said that every time she speaks with a survivor, she carries that story with her — not just as a journalist but as an Indigenous woman. Walker is an investigative journalist from the Okanese First Nation in Saskatchewan and identifies as Cree. In the more than two decades Walker has been a reporter, she has become a trusted voice in reporting on Indigenous issues in Canada and beyond. After graduating from the University of Regina’s School of Journalism, Walker began her career at the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), where she worked for nearly two decades, covering everything from missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG) to systemic abuse within state institutions.

Walker’s work is a testament to the power of journalism rooted in community, history, and healing, and has gained international recognition through deeply reported podcast series such as Missing and Murdered and Stolen: Surviving St. Michael’s. The latter not only won a 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Audio Reporting and a Peabody Award — the first podcast to win both in the same year — but also helped bring long-silenced stories to public consciousness and secured her a place at the forefront of investigative audio storytelling.

In this Q&A, part of GIJN’s ongoing interview series with leading investigative journalists, Walker reflects on how she makes sure she centers her sources in her reporting, how she builds trust, and the advice she gives reporters who want to tell stories with depth and accountability.

GIJN: Of all the investigations you’ve worked on, which has been your favorite and why?

Connie Walker: The investigation that had the most impact on me personally and professionally was definitely Stolen: Surviving St. Michael’s. It was such a personal story because we were investigating my dad’s experience at a residential school in Saskatchewan.

Although I talked about my personal life in other investigations, this was the first time my family was the focus. But I also think having that personal connection made it more impactful.

I got to really know my dad in a new way, and understand how what happened to him at that residential school shaped the father he was to me. I’m incredibly grateful to have had that experience. Then, when the podcast came out, I heard from other intergenerational survivors who told me that it felt like I was helping them understand their own family story.

GIJN: What are the biggest challenges in terms of investigative reporting in your country?

Connie Walker’s 2022 podcast Stolen: Surviving St. Michael’s won both a Peabody Award and a Pulitzer Prize for Audio Reporting. Image: Screenshot, Gimlet Media

CW: Most of my reporting has been in Canada. I’ve only done in-depth for a few seasons in the US. It’s interesting because the thing that comes to mind initially is how open to media law enforcement was in the United States. [Working on] Stolen and Trouble in Sweetwater, for both of those seasons, we had pretty good access with law enforcement to be able to share about open investigations.

But with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police or the Ontario Provincial Police, if it’s considered an open investigation, they won’t even give you an interview — only statements. Even if the cases are decades old and there are questions about how open they are.

GIJN: What’s the greatest challenge you’ve faced as an investigative reporter?

CW: The conversation around understanding the truth of our colonial history in Canada and the United States has been a major challenge. In terms of the conversations and the level of understanding around truth and reconciliation and Indian boarding schools, these are much better understood in Canada.

Of course, there are serious issues with people denying residential school history — but it’s not as well known in the United States. In Canada, the work around awareness has been largely led by survivors and the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Despite the fact that there’s obviously more work to do, we can’t lose sight of the radical transformation that has happened in this country over the last 15 years. Fifteen years ago, there was very little interest. That didn’t change for well over a decade.

On the last National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, I was in the car with my kids, and we decided to count the number of orange shirts [a show of support for survivors of residential schools and the reconciliation process] we saw. We saw double or triple the amount we’d seen in previous years; it was a visual representation of how much this awareness has grown. It was mostly youth and young people.

One of the biggest challenges was trying to shift those attitudes in the media to try to understand what was missing from journalism, from our newsrooms. For so long, there was really an underrepresentation and, therefore, a misrepresentation.

GIJN: What is your best tip for interviewing?

CW: For stories of those who have experienced trauma, especially survivors of Indian residential schools, whenever I’m about to talk to someone who has that experience I want to make sure I create a space that is both inviting and safe and really give people space to share, because I often find that people have been thinking about this interview before it happens.

They often have something specific to say, and I try to give them the space to say that initially, and that they have the agency to share that. It’s their story and their life — and their interview.

I also communicate it verbally and non-verbally. I don’t want to step on anyone’s words. I make eye contact. I’m terrible at TV interviews because you can see my head bobbing. I’m non-verbally trying to say: “I’m here for you, I’m taking this really seriously.” Those little things have gone a long way. [The source] can feel like they have the power and control, and that’s so important when they’ve been victims of any kind of abuse, traumatic events, or people who are underrepresented in society.

You want to correct as much as you can, the past harm that has happened by the media in general.

GIJN: What is a favorite reporting tool, database, or app that you use in your investigations?

CW: For podcasting in particular, we use a program called Descript. I don’t know exactly how to edit podcasts, and I work with incredibly talented people who do that. Descript is good for me, because I don’t have those exact skills. You can see how things sound without sending it to an engineer. But the one thing I will say about tools is that I came up at a time when there was still the capacity and space to learn from one another. So much of my education has been hands-on learning from my colleagues. They are some of the kindest and most generous people out there.

There’s an incredible community within journalism, and we can all rely on each other. They are the biggest tool and support.

GIJN: What’s the best advice you’ve gotten thus far in your career, and what words of advice would you give an aspiring investigative journalist?

CW: My friend, the journalist Duncan McCue, coined this idea: ‘Be a storyteller, not a story taker.’ This really resonated with me.

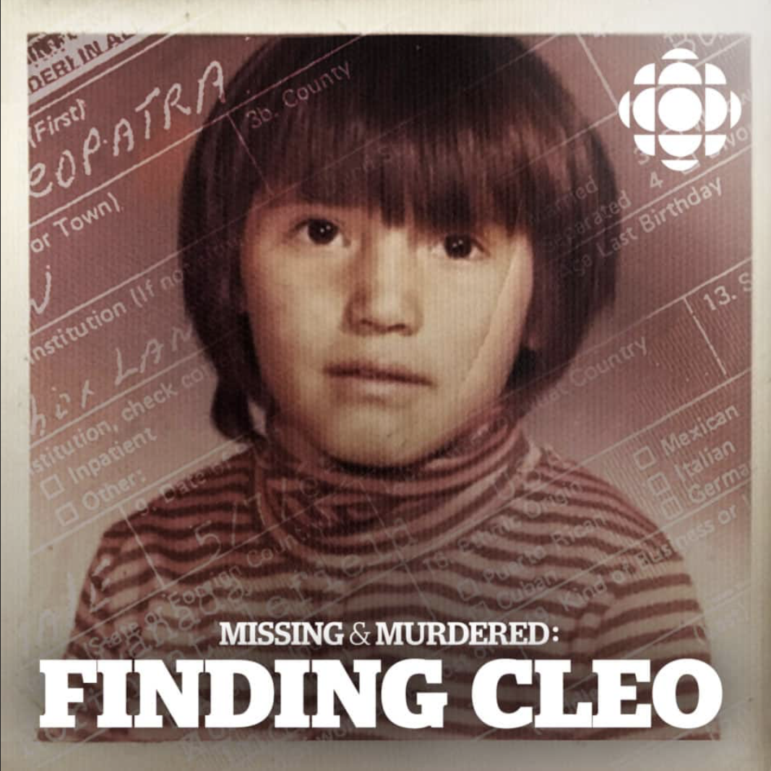

In this 2018 podcast, Connie Walker investigated the relocation of an Indigenous girl, Cleo, who was taken from her family in the “Sixties Scoop.” Image: Screenshot, CBC

And it’s something I took forward while reporting Finding Cleo, which is about a young Cree family that had been scattered across North America in the Sixties Scoop. We had been contacted by Crystal Semaganis, who wanted to find her sister… and we were trying to make sense of their experiences that were often traumatic. And at one point, our producer and I arrived at Little Pine First Nation, and we met with the chief and cousin of the Semaganis family.

Within an hour of arriving, we were sitting in a teepee. I was smelling the sweet grass in the air and I remember how good I felt. Because this was familiar to me. The chief knew my dad. It felt amazing to be back in Saskatchewan.

But then it hit me that Crystal was the one who was longing to connect with her family and community. Through the Sixties Scoop, she was cut off from her language and her family.

I felt that I had become a story taker instead of a storyteller. It really changed the way we proceeded with the rest of the family. That was an important lesson for me… it’s just trying to be as aware as possible and thoughtful about your place in the story.

GIJN: What is the greatest mistake you’ve made?

CW: I feel like for every single story, I’m terrified of making mistakes because the stakes are so high for the people involved in the stories.

The fear is: so many of the missing and murdered Indigenous women stories are about someone who is missing, or who has been killed, and you’re interviewing their family. I’m worried about leaving people in a worse space than before I arrived… and you’re trying to navigate a lot of tricky ethical considerations in your reporting.

GIJN: So how do you approach those ethical issues when dealing with stories that involve trauma?

CW: The way I’ve tried to navigate through that is by taking a team approach. I’ve been lucky to work with talented teams of journalists in the podcasts I’ve made, thoughtful people who have different kinds of experiences.

I can rely on their editorial input, and that’s been a valuable resource. Podcasting is a team sport; there’s just no way around it, and it can help minimize some of the mistakes you make.

GIJN: How do you avoid burnout in your line of work?

CW: Having a supportive team is really integral to doing this kind of investigative work, it helps share the responsibility.

I’m often in therapy, especially during really tricky kinds of reporting or production times where I need extra support. I have, maybe you’d call it an obsession with crafting. The busier I am, I feel a compulsion with sewing, knitting, and embroidery. Making something with my hands is such a stress reliever.

GIJN: What about investigative journalism do you find frustrating, or do you hope will change in the future?

CW: The access to information systems is always frustrating. I wish there were just better processes in place for governments to share information. I would also just say that investigative journalism is often expensive, and we want to be as thorough as possible. Personally, it’s a frustration because it’s more challenging to do it now. I wish there were a better or easier way.

Olivia Bowden is a freelance journalist based in Toronto who primarily focuses on health, race, and social justice issues. She was previously a reporter for CBC News, The Toronto Star, and CTV National News.

Olivia Bowden is a freelance journalist based in Toronto who primarily focuses on health, race, and social justice issues. She was previously a reporter for CBC News, The Toronto Star, and CTV National News.