Key Terms

Full guide here. العربية

Forced labor, human trafficking and undocumented migration are prevalent across the globe. In the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, specific and shared characteristics of labor and migration laws and practices facilitate forced labor and human trafficking.

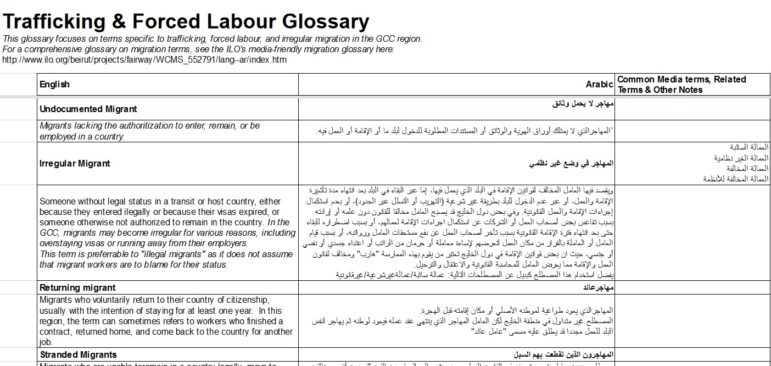

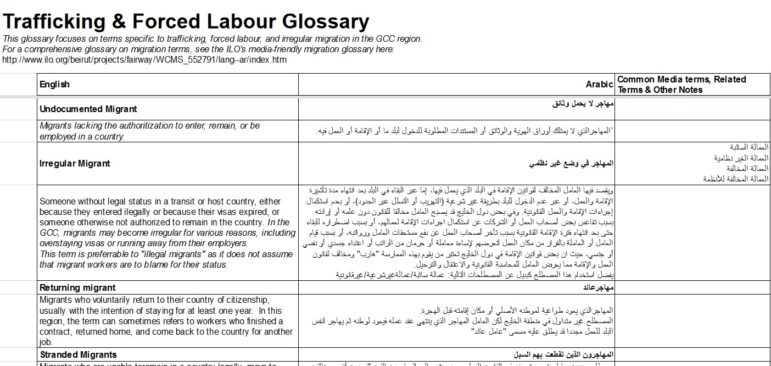

Definitions

Forced Labor. All work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty or coercion, and for which the said person has not offered himself or herself voluntarily. The threat of penalty may include arrest or jail, refusal to pay wages, forbidding a worker from traveling freely, confiscating worker’s identity documents and withholding part of a worker’s salary as part of the repayment of a loan. Misleading workers about the nature of the work also characterizes involuntarily work.

Forced Sexual Labor. Forced labor and services imposed by private individuals, groups or companies involving commercial sex.

Debt Bondage. Labor and services in exchange for the repayment of debts. Migrant workers often take on large loads to find work abroad, and have little ability to reject work as their salaries are used to pay back these loans, with or without the direct involvement of their employer. Debt bondage is considered a risk factor for modern slavery.

Modern Slavery. It is important to note that the term “modern slavery” is not a concept defined in international law, though it is often used to describe forced labor and has become associated particularly with labor supply chains. In the latest Global Estimate on Modern Slavery, the term also encompasses forced marriages.

“Illegal” Migration/Migrants. Migration that takes place outside the regulatory norms of the sending, transit and receiving countries. “Illegal” migrants may include those who entered the country regularly but whose valid residency has lapsed for whatever reason.

Note: The term “illegal migration” is often used by governments and in state publications, but scholars and civil society activists warn that their use carries negative connotations. In this region particularly, the term obfuscates the complicity of the state and employers in making migrants undocumented. Alternative terms include “irregular migration” and “irregular migrants.” These terms do not have a fixed or legal definition.

Human Trafficking. The recruitment, transportation, transfer, harboring or receipt of a person often over international borders — but also frequently within the boundaries of a single country — for the purpose of exploitation. This can include the threat or use of force, deception, abduction, the abuse of power or a position of vulnerability or other forms of coercion. The purpose of human trafficking is exploitation, which can include the prostitution of others, forced labor, slavery or servitude.

Risk Factors for Human Trafficking

- Lack of information for potential migrants about safe migration opportunities and the dangers of trafficking.

- Raising of barriers to legal immigration. For example, employment bans from either country of origin or destination.

- Demand for sexual services or inexpensive labor.

- Vulnerabilities linked to discrimination and irregular status of migrant workers.

Common Issues in the Region

Contract Substitution

Workers often a sign a contract with the recruitment agent in their origin country which differs from the contract they sign once in the country of destination. Various countries have taken steps to address this common practice, though agents continue to work around regulations. Workers may sign contracts for wages lower than expected, be forced to work longer hours or may work in a different position entirely. Contract substitution is especially likely to occur through undocumented migration routes.

Contract substitution is a subset of deceptive recruitment practices. Middlemen or recruitment agents sell migrant workers on dreams of the riches they’ll make in the Gulf, promising wages and working conditions far from the reality these workers will endure.

Excessive Recruitment Fees

Though employers are required by GCC laws to pay for all recruitment fees (including flights), migrant workers often pay their own recruitment fees in the country of origin. These can be excessively high fees which workers take out a loan to pay, or are indebted to the recruiter (see above, “Debt Bondage”) and must directly remit portions of their salary to the recruiter. Employers may also deduct fees they have paid to recruiters from workers’ salaries, though this appears to be a less common (or at least, reported) as three Gulf states have implemented “Wage Protection Systems” to monitor workers’ salaries, with varying levels of success (see below, “Unpaid Wages”).

Unpaid Wages

Nonpayment of wages is another common practice in the GCC states which has not been fully tempered by the implementation of Wage Protection Systems. The practice is not restricted to any particular sector, though the longest periods of unpaid wages may affect isolated workers (such as domestic and agricultural workers) most as they are often less able to report abuse or escape their work site. However, nonpayment of wages is also found in larger companies that go bankrupt or experience issues with cash flow. A recent example is the Saudi Oger case.

Free Visa

The “Free Visa” is a term used for the common practice of migrants paying sponsors for valid residency, but working as a freelancer for multiple employers. With few exceptions, migrants in the Gulf are only permitted to work for the employer who sponsors them (unless their employer is a registered subcontractor and they are deployed to multiple job sites). The Free Visa can earn migrants more money than they would otherwise make with a single employer. Common users of the Free Visa include domestic workers and laborers.

Migrants working under the Free Visa are not always victims; some prefer this scheme because it allows them greater flexibility with their schedules, more control over the types of jobs they choose to take on and greater earning potential. But the Free Visa can turn exploitative if the sponsor or one of the worker’s irregular employers threatens to turn the worker in, demanding a higher fee or refusing to pay owed wages.

Buying and Selling of Domestic Workers

Domestic workers in particular are vulnerable to the “maid trade,” which comes in various forms. Agents traffic domestic workers between GCC countries and either obtain proper paperwork for them in the country of employment or leave them undocumented. This often occurs when a country of origin has placed a moratorium on domestic workers to a certain country; the demand for domestic workers becomes more difficult to meet through regular channels and the black market flourishes.

The “maid trade” also occurs within countries and to those with valid visas and residency documents as employers “sell” their domestic worker — meaning they receive payment for handing over the sponsorship of the worker. This is sometimes an easier choice for employers who do not want to go through an agent to recruit and bring someone new from abroad. This becomes more common in countries which have banned the deployment of domestic workers from a particular country, as employers may have a preference for a domestic worker of a particular nationality.

Trafficking and Forced Labor

Many of the above practices are widespread and considered “normal.” This means that any “ordinary” employer can be complicit in human trafficking. These behaviors and acts are so entrenched, and to a large extent facilitated or tacitly consented to by the law, that many are not aware that their actions amount to trafficking. Given the multiple actors involved in labor migration, it is possible that one party (the recruitment agent or the employer) has trafficked a migrant without the other party’s knowledge. Making employers more conscious of the recruiters used, and making recruiters more conscious of the employers they send migrants to, is a necessary step towards reducing this practice.

It is important to note that despite apparent anti-trafficking initiatives in some countries, the issue remains inadequately and incompletely addressed. State initiatives often focus exclusively on sex trafficking, paying scant attention to labor trafficking. Furthermore, victims of trafficking are likely dissuaded from coming forward due to fear of incarceration or deportation. States very often undercount the number of trafficking incidents in their countries; the US Trafficking in Persons Report offers a credible assessment of countries’ efforts to tackle these issues.

Undocumented Migrants

Migrants often experience more than one of the situations above, compounding the difficulty of leaving employment. Those that do choose to leave an abusive or unhappy employment environment often have little recourse to change employers because of restrictive sponsorship laws and practical obstacles to confronting employers in court. Migrants who leave their employment situation without their employer’s consent are reported as “absconded” workers and their status almost immediately becomes that of an “illegal” migrant.

Workers who wish to leave an employment situation also face difficulty returning home. In Qatar and Saudi Arabia, migrants who wish to leave the country must obtain permission from their employers in the form of exit visas. In other countries, passport confiscation prevents workers from leaving — even for the few low-income migrants that can afford the ticket home or can afford to forsake the costly recruitment fees they paid to get into the country.

Kafala System

The Kafala System — or sponsorship system — varies across each of these countries, but one common consequence of the system is a large undocumented migrant population. State authorities and media often refer to migrants lacking valid residency documentation as “illegal,” but journalists should eschew this term for several reasons. Firstly, the designation is dehumanizing and feeds into stereotypes about migrants’ inherent criminality. Secondly, the term obscures the culpability of employers and unfair regulations in a migrant’s undocumented status.

There is no such term as “illegal employer,” though it is often the actions of an employer which push migrant workers into an undocumented status. In most cases, the sponsorship system prevents or presents serious obstacles to workers changing employers and remaining in the country legally. These undocumented workers form a critical component of local economies, often working in local shops or as freelance domestic workers and laborers.

GCC countries regularly carry out raids against undocumented workers, rounding them up for deportation. These states also occasionally grant amnesty to undocumented workers, permitting them to return home without penalty or blacklisting with the cooperation of their embassies. But these amnesties also absolve the employers of accountability, as authorities make no effort to address the causes of migrants’ irregular status. Amnesty periods are often followed by an intensified crackdown on undocumented workers, but little structural policy change means the issue of irregular migration — and forced irregularity in particular — continues.

There are few reliable statistics on the number of undocumented workers in the region. Police or Ministry of Interior reports may indicate the number of migrants deported during a particular period, especially during amnesty periods. But origin country embassies and authorities most often track of deported citizens.