Illustration: Marcelle Louw for GIJN

Health and Medicine Guide: Reporting About Safety

Read this article in

Guide Resource

Investigating Health and Medicine

Chapter Guide Resource

Health and Medicine Guide: Preface & Introduction

Chapter Guide Resource

Health and Medicine Guide: Regulating Drugs — Development & Approval

Chapter Guide Resource

Health and Medicine Guide: A Study Is Not Just a Study

Chapter Guide Resource

Health and Medicine Guide: The Scientific Basis of Influence

Chapter Guide Resource

Health and Medicine Guide: Behind-The-Scenes Reporting Strategies

Chapter Guide Resource

Health and Medicine Guide: Reporting About Safety

Chapter Guide Resource

Health and Medicine Guide: Tips on Traps, Hype & Ethics

Chapter Guide Resource

Health and Medicine Guide: Appendix

Editor’s Note: This guide to reporting on health and medicine issues was originally published in November 2020, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Original authors Serena Tinari and Catherine Riva have updated it as of November 2024.

First Do No Harm

Once a medical or pharmaceutical product — a drug, vaccine, or medical device — has gone through the different testing phases, and the approval process with regulatory agencies, it hits the market and can be prescribed and sold. Serious adverse events can appear when the product is widely used for the first time by real patients. This relates not only to potential flaws in scientific research and problems related to regulatory approval and reporting in scientific journals. It is also sometimes a matter of numbers: If you test a drug or device’s safety on 5,000 patients, an adverse event arising in one out of 20,000 people might not arise until many more patients use the product. Therefore, the first 10 years after a drug is approved are considered especially important to spot harms.

Assess the Evidence

Editors love stories about the damage caused by drugs, vaccines, and medical devices because they are popular with audiences. This approach has gone through some changes during the COVID-19 crisis, where even mentioning the possibility of pandemic vaccines causing adverse events resulted in journalists being labeled in derogatory terms. However, no drug or vaccine comes with zero side effects, and medicines approved through fast track and accelerated approval procedures are particularly susceptible to eventually show some negative impacts.

In a nutshell, in the field of damage caused by medicine, there are also a plethora of potentially good stories waiting to be told, but many pitfalls await and careful reporting is required.

First, one needs a systematic understanding of drug development and testing, including a review of the related literature and data. As we have seen in the first chapter, a few thousand people or so will have tested a medical product in a controlled environment before it goes to market. That’s why, although there are exceptions, “new drugs” are generally considered less safe than older ones. Simply put, they just aren’t as well understood medically.

What is defined as “post-marketing surveillance” by regulatory agencies is important. This includes pharmacovigilance, a type of monitoring that the WHO defines as “the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding, and prevention of adverse effects or any other drug-related problem.”

When pharmacovigilance is based on voluntary reporting, this can be a major issue. There are several ways for doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and patients to report suspected side effects, including by reporting them directly to regulators. If such reports are considered credible, national regulatory bodies may forward them to the WHO Programme for International Drug Monitoring in Uppsala, Sweden. The reports are not public; as a journalist, you can have access to them if a patient or a doctor shares them with you. Regulators may provide statistics from the reports, but even though personal identities are masked, the full reports are still considered highly confidential.

Underreporting of the adverse reactions to medical products is perhaps the most troubling weakness of this system. Only a tiny fraction of adverse events are ever reported, according to a comprehensive study from 2006. However, journalists should be wary of relying on a single report of an adverse reaction. These are called “signals” that tell experts to do further research into causality. Many other factors may have contributed. A single report needs to be evaluated along with other evidence.

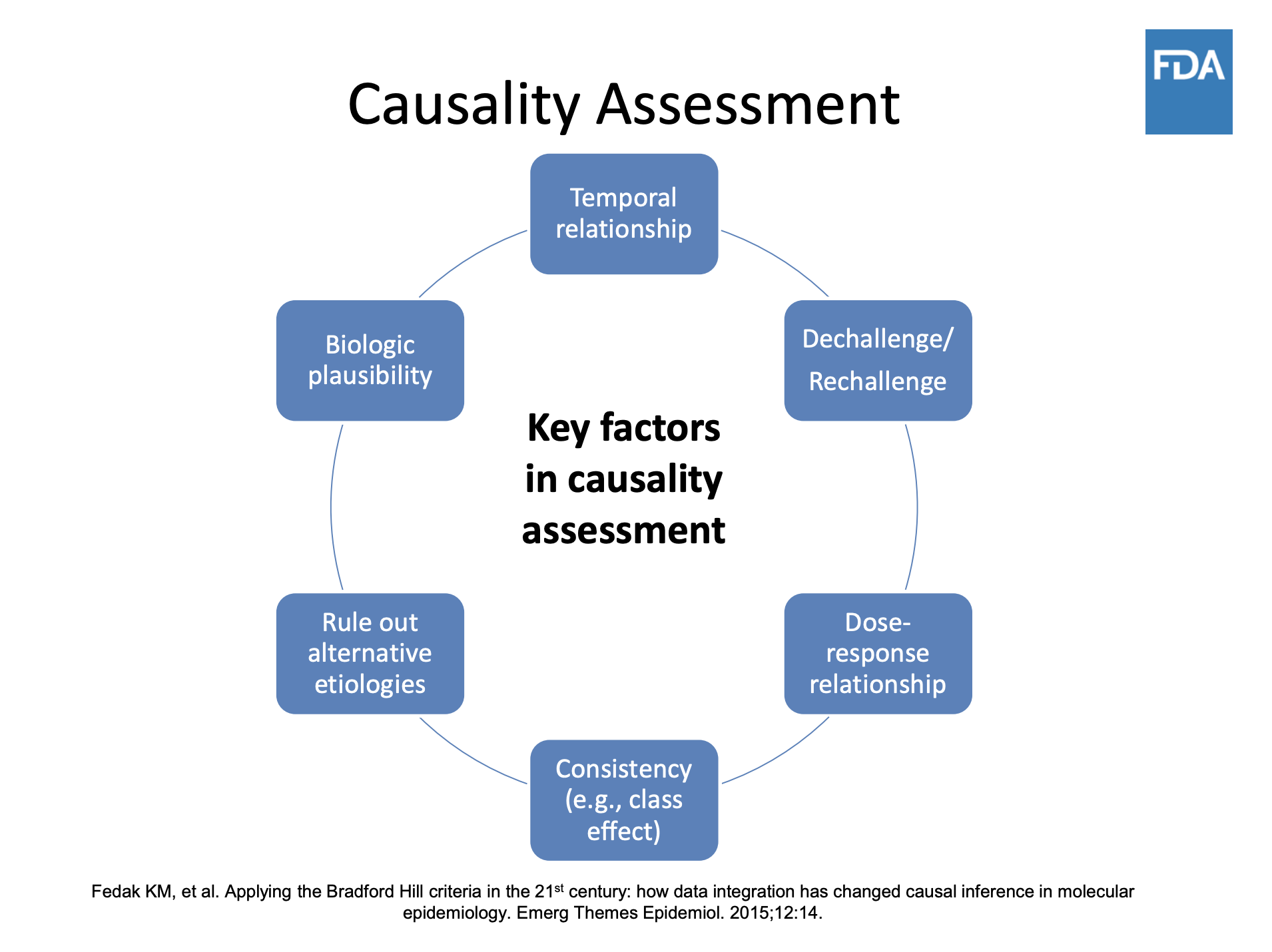

Illustration: US Food and Drug Administration

Typically, news stories affect the reporting of adverse event reporting (called AER). If there are news outlets reporting on a drug’s alleged dangers, in the weeks that follow regulatory agencies will record a significant increase in reports. Events reported by patients, although considered of lower quality than those filed by medical professionals, have real potential to improve the system, as pointed out in the article Patient Reporting Is the Future of Pharmacovigilance by Sten Olsson, then-president of the International Society of Pharmacovigilance. Keep in mind that exposing evidence will not necessarily lead to a drug being pulled off the market. Regulatory procedures are often more complicated. Your reporting may push regulators to modify the drug label, a process where extensive negotiations with the pharmaceutical company’s marketing firm will take place.

Retrieve Data and Talk to the Victims

There is a big difference between the safety data collected during development and approval and the data that emerges post-marketing.

All reports about the side effects of a drug from a WHO member country from 1968 onwards are stored in VigiBase and remain available, even if the products are no longer on the market. You can request access to the data available by filing a request with national regulatory agencies.

The data come with many caveats and are truly hard to analyze, as a single case can be recorded under several different codes. However, health stories need real humans speaking about the harms or damages they have experienced. “Case reports” are always anonymized, so when you receive data from pharmacovigilance officers, you need strategies to find such alleged victims. One is through doctors: They may have a patient who is willing to talk to journalists. Or they may know another doctor whose patient experienced that side effect.

Social media sites offer many possibilities via crowdsourcing, as do websites and newsletters of your media outlet. Posting an open call that states clearly that you are investigating the potential harm, or patients’ experience with a pharmaceutical product, will expose your ongoing project but will give you the greatest chance of getting in touch with potential protagonists.

So, let’s imagine you came across a potential harmful product and even identified potential characters for your story, patients that allegedly were harmed by that product. What do you do next? The key is to independently assess the evidence and compare your findings with studies published in the literature.

Often victims’ stories have not been reported at all. Telling their stories may provoke responses from patients or families contacting your newsroom. Collect all the cases, complete with medical details, and don’t forget to ask them to sign a waiver of their physician-patient privileges. Without this waiver, your investigation will be delayed, as doctors and hospitals will refuse to respond to your requests until you have the waiver, since most national laws protect the privacy of patient medical information, and some are quite strict.

When you have a complete picture of specific cases, present the evidence to the regulators. Experience has shown many times that it’s useful to contact them before your investigation is concluded and well before publication. If your methods are solid, and you have discovered facts that are in the public interest, it’s actually in the regulators’ best interest to support your work. Of course, they won’t give you the names of patients or information that puts them in a bad light. But they may point to aspects you might have underestimated (say a study, or data, or a specific rule applying to the case), so they can help you avoid errors in your reporting. Sometimes, they may even hint at the pharmaceutical company or the doctors’ organization that played a role in delaying or hindering regulators’ work. At the same time, the industry often uses a strategy of information overload when responding to queries from investigative journalists. Expect lengthy statements and references to studies replete with scientific jargon. Since some pharmaceutical or medical products represent the potential for millions (or more) in profits, investigative journalists might also face cease-and-desist letters or other legal threats to quash their reporting before it is made public.

Serena Tinari’s Skin To Die For investigation for the Swiss public broadcaster on acne drug Accutane’s psychiatric side effects, led to a wave of patients and their families sending us their testimonies. Out of more than 300 reports Tinari, who is also co-author of this guide, received, 61 cases were included by the Swiss regulatory agency Swissmedic in the national and global database on drug safety. The agency also issued an update to prescribers and patients on the drug’s psychiatric risks.

Similarly, the medical devices investigation by Jet Schouten, a journalist with Dutch public broadcaster AVROTROS which inspired the ICIJ Implant Files project, was sparked by the many testimonies the broadcaster received after publishing its first story.

Finding sources of all kinds for such an investigation can be complicated. Crowdsourcing and social media searches are key. Use advanced research tools like those listed in GIJN’s guide to online research.

Court proceedings can be a trove of information, as well as a place to look for sources, particularly if you are investigating harmful effects and damage.

Getting too close to your sources is never a good idea, however, and it certainly should be avoided when reporting about drug safety. When you are presented with a situation where patients weren’t properly informed, regulators knew but didn’t act, potential or real conflicts of interest, or highly knowledgeable experts with huge reputations, it is tempting to rely too much on one or two sources. Your duty is to assess the evidence and expose wrongdoings, not make new friends.

It’s also important to use careful, accurate language, and not to hype your drug safety story. Inflammatory language simplifying the risk-benefit ratio and distorting the scientific evidence will leave space for the authorities to ignore the matter. Poor quality reporting could even inhibit intervention by regulatory authorities. Sensationalized stories could prompt patients to stop taking a drug without talking to their doctor, which could be dangerous to their health. Hyped coverage may lead to actions which are not evidence-based, such as pulling a drug from the market instead of modifying prescription guidelines to make sure it is taken correctly.

Expose Fraud, Scientific Misconduct, and Medical Malpractice

From nursing homes to research labs, from public hospitals to medical practices, health care is affected by fraud and misconduct. Many of the cases would not have come to light without the wrongdoing being exposed by victims, prosecutors, human rights advocates, and journalists. Here’s a list of some of this inspirational and instructive work.

In some cases, it was necessary to go undercover. In 1887, US groundbreaking journalist Nellie Bly pretended to be mentally ill to investigate reports of brutality and neglect at a New York psychiatric institution. Fast forward more than 100 years, and Naziha Syed Ali also went undercover in Pakistan to dig deeper into organ trafficking for Doctors, Police and Middlemen. So, too, did a BBC Africa Eye team led by Solomon Serwanjja for Stealing from the Sick, an investigation exposing the black market of pharmaceuticals in Uganda.

Victim testimonials are key, as in Deborah Cohen’s BBC story on stem cell experiments, or in the Thomson Reuters Foundation investigation led by Roli Srivastava: Missing Wombs: The Health Scandal Enslaving Families in Rural India.

Medical malpractice can be analyzed by combining data with victims’ accounts, as Peruvian outlet Ojo Público is pursuing with the project Cuidados Intensivos. Or see journalist and former molecular cell biologist Leonid Schneider’s investigation into an alleged case of scientific misconduct involving trachea transplants. That story is also featured in Benita Alexander’s documentary “He Lied About Everything” (Discovery) and Bosse Lindquist’s three-part documentary “The Experiments” (SVT). In 2022, Surgeon Paolo Macchiarini was convicted by a Swedish court of “causing bodily harm.” A year later, that story was featured in the Netflix documentary series Bad Surgeon: Love Under the Knife.

Another good read is Tide of Lies by Kai Kupferschmidt about the long journey of researcher Alison Avenell in exposing a major case of scientific fraud that highlights the many problems affecting biomedical journals.

One other disturbing example of medical misconduct can be found in Sushma Subramanian’s in-depth piece for Slate, Worse Than Tuskegee, on how in the 1940s American researchers infected Guatemalans with syphilis and gonorrhea, then left without treating them. The case emerged in 2003 thanks to Susan Reverby, a historian at Wellesley College. Equally troubling: the case told in a longread published in 2022 by the Australian outlet Quillette: “The Philadelphia Experiments – How an enterprising doctor, an elite university, and negligent public officials turned a city prison system into the largest human research factory in America.”

The Wall Street Journal’s John Carreyrou, who won a 2015 Pulitzer Prize for his Medicare Unmasked series, began a groundbreaking investigation that same year on blood testing firm Theranos that resulted in the book “Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup,” a subsequent Netflix series, and, ultimately, fraud indictments and convictions for two of the company’s founders.

There is much to investigate in the area of so-called “corporate crime.” Two references guaranteeing you sleepless nights: Peter C. Gøtzsche’s book “Deadly Medicines and Organised Crime” (extract on BMJ: Big Pharma Often Commits Corporate Crime, and this Must be Stopped) and Public Citizen’s Thirty-One Years Of Pharmaceutical Industry Criminal And Civil Penalties: 1991-2021.

Don’t Be Afraid to Ask Inconvenient Questions

Investigating adverse effects of a vaccine can be challenging. The subject tends to be hijacked by opposing factions who clash over a question of principle: being for or against “vaccination”, irrespective of the product and its indication. This leaves little room for a factual analysis of the information available on the safety of a given product.

Furthermore, the problem of under-reporting in the pharmacovigilance system is even more acute for vaccines, due to the tension surrounding the debate and concerns by the healthcare workers supposed to be filing reports of potential side effects. Recent contributions in the BMJ have also highlighted significant dysfunctions of the US Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS).

If you decide to investigate a vaccine adverse event, it’s therefore important to take a few precautions. First, don’t be dissuaded by those who claim that asking questions would endanger vaccination. As this Nature article on behavorial science lessons from encouraging vaccine uptake found:

“The questions people usually ask and want answers to are: is the disease bad enough to warrant vaccination; is the vaccine effective; are there side-effects or long-term harms? Research has shown that explicit discussion of trade-offs in addressing these questions, rather than avoiding any acknowledgement of risk, did not harm overall support for vaccination or trust in health authorities.”

Remember that, unlike other drugs, vaccines are usually administered to people in perfect health: their benefit-risk ratio must therefore be extremely favorable. Thus, it is even more legitimate to hold regulatory and health authorities accountable: they are responsible for defining the safety requirements vaccines must meet in order to be marketed, and they have the power to demand the manufacturers to provide all relevant data.

You will also need to review the literature, where interesting cases might have been featured. Take a look as well at the regulatory documents regarding safety: signals (even statistically not significant) might appear. Finally, always put the data from unvetted sources like VAERS and other national databases into context. These are so-called “passive reporting systems”, and the included cases cannot be considered evidence. However, they can and are used for signal detection. But to make an estimation of risk at the population level from which conclusions on causality are drawn, cases need to be numerous and must be analyzed through a complex procedure (assessment, development of causality hypothesis, and testing of the hypothesis).

The discovery of myocarditis in young men shortly after the injection of a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine is an interesting example. When a public health authority announces it will investigate a signal of post-vaccination side effect, it has a knock-on effect which allows for others to more quickly gather evidence to elucidate the existence of a causal relationship. For example, in April 2021, the Israeli Minister of Health announced his intention to investigate myocarditis cases in men under the age of 30 vaccinated with Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine. The announcement prompted authorities around the world to investigate the situation in their own country or region. In July 2021, regulatory agencies added to the product information a warning for increased myocarditis risk after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination in men under 30.

Serena Tinari is a co-founder of Re-Check.ch, a Swiss nonprofit organization dedicated to investigating and mapping health affairs. She as been working across print and electronic media, radio, and television since 1994. She authored dozens of investigative stories for the Swiss public broadcaster. Tinari specializes in drug safety, Evidence-Based Medicine and conflicts of interest. A trainer, speaker, and moderator, she has reported extensively on swine flu and Tamiflu.

Serena Tinari is a co-founder of Re-Check.ch, a Swiss nonprofit organization dedicated to investigating and mapping health affairs. She as been working across print and electronic media, radio, and television since 1994. She authored dozens of investigative stories for the Swiss public broadcaster. Tinari specializes in drug safety, Evidence-Based Medicine and conflicts of interest. A trainer, speaker, and moderator, she has reported extensively on swine flu and Tamiflu.

Catherine Riva is a co-founder of Re-Check.ch, a Swiss nonprofit organization dedicated to investigating and mapping health affairs. She specializes in the design and methodology of clinical trial, public health, and Evidence-Based Medicine. A trainer and a speaker, Riva has reported on the Mediator case, breast cancer screening programs, the controversies related to HPV vaccination, and on conflicts of interest in healthcare and medical research. She has also published in biomedical journals.

Catherine Riva is a co-founder of Re-Check.ch, a Swiss nonprofit organization dedicated to investigating and mapping health affairs. She specializes in the design and methodology of clinical trial, public health, and Evidence-Based Medicine. A trainer and a speaker, Riva has reported on the Mediator case, breast cancer screening programs, the controversies related to HPV vaccination, and on conflicts of interest in healthcare and medical research. She has also published in biomedical journals.