How Taiwan’s The Reporter Created a Chart-Topping Podcast

Jason Liu at a podcast listeners event. Photo: Courtesy of Jason Liu and Lan Wanchen

The Real Story is a podcast from the team behind The Reporter, an investigative journalism outlet in Taiwan. It surged to the top 10 of Apple Podcasts in Taiwan shortly after launch, making its “best of” 2020 list for the country, and won a number of other “hot show” and “best new program” awards, highly unusual for news-based podcasts.

The Reporter, a nonprofit newsroom and GIJN member organization, is known in Taiwan for its in-depth investigative stories and has made a name for itself digging into slavery in the offshore fishing industry, the conditions of child and migrant workers, and human rights issues.

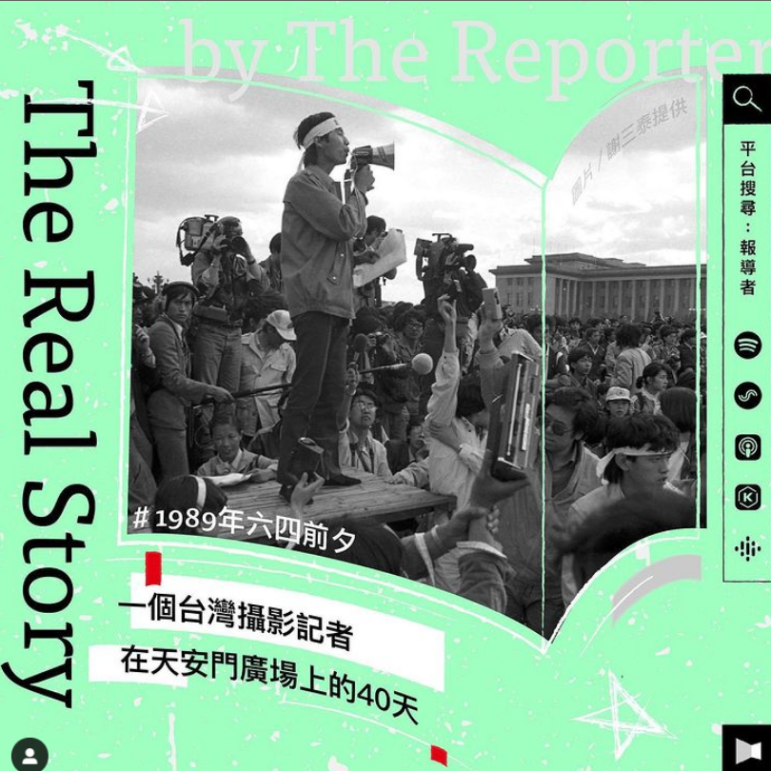

The Real Story delves into similar subject matters, creating a new space in Taiwan’s journalism sphere, in which investigative reporting is mixed with a podcast format. Recent episodes have covered protests in Thailand, misinformation and the pandemic, and the photographer who documented the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989. It is not exclusively investigative, also running features and lighter stories, but the high-quality broadcasts and interesting subject matter have garnered the podcast a loyal following.

With more than 50 episodes under their belt, the team behind The Real Story presents the weekly podcast in a variety of formats: blending interviews with investigative reporters and editors, current affairs discussions with researchers, and more feature-based audio documentaries. The podcast, which is broadcast in Taiwanese-accented Mandarin, has over 100,000 subscribers and has been played nearly 9.5 million times. Some listeners are in Hong Kong and China, but most are in Taiwan. The demographic skews younger than the readers of The Reporter, and listeners tend to be highly engaged and communicate with the team across a variety of platforms.

How has the team made a success of their podcast in such a short time? How do they pick appropriate stories for the show, and maintain audience engagement when covering complicated investigative topics? And what can they teach other investigative outlets worldwide about setting up a podcast?

GIJN interviewed host Jason Liu and producer Lan Wanchen, and asked them to tell us about their experience in making investigative podcasts, and their tips for making a program that audiences want to listen to.

Listen to the original interview here (in Chinese):

Q: Why did you want to create a podcast for the team behind The Reporter in the first place?

Jason Liu: In August 2019, I used to be a guest on a podcast in which I talked about the special reports and investigations I was working on. Lan Wanchen was the producer of that podcast. One day, after a show, I said that the in-depth nature of The Reporter would make it perfect for making this kind of audio content. She took the initiative from there.

After an internal analysis, The Reporter distributed a questionnaire to readers in the first half of last year. A total of 1,599 feedback forms were received, showing that 95% of readers who listen to podcasts wanted The Reporter to launch one, so we decided to start The Real Story.

Q: Who makes up the team?

Lan Wanchen: The team is mainly composed of three people: host Jason Liu (who is also the deputy editor-in-chief of The Reporter); myself, the producer; and community operations officer Hung Chin-hsuan. In addition, photojournalists, engineers, and marketing staff also help us.

Jason is primarily responsible for story selection, recording interviews, writing the scripts, and editing after the recording is completed. He will listen to me and Hung Chin-hsuan in the process. After the interviews, all the recording materials are handed over to me for post-production, including processing the sound quality of the recording, adjusting any necessary information, and to manage the flow of sound effects and music.

When the story is ready, Hung Chin-hsuan is responsible for editing and checking the program title and promotional copy, and finally putting the program on-air and promoting it on major social media platforms.

Producers Lan Wanchen (left) and Jason Liu (right) preparing for an interview. Photo courtesy of the interviewees

Q: How long does the production cycle of each program take?

Jason Liu: Our shortest program production cycle is one to two days, usually for breaking news topics — like one we did on Taiwan’s algal reef issues. There are also longer production cycles. Sometimes we collect a lot of sound material in the preliminary interview, which leads to a lot of time spent in post-production; on other projects, we spend a lot more time in the earlier planning stages. Sometimes the audience asks questions about a certain topic, which leads us to start work on a particular program, so the length of production time mainly depends on the episode itself.

Usually after deciding on a topic, we will think about which format would work well, and what materials we have. This will include who can be invited as guests, an analysis of what is happening, and after doing an inventory of what the material is and determining the format of the program, we decide on the production cycle.

Topic Selection

Q: How do you pick what topics you will cover on The Real Story? What are the criteria for determining the subjects you will cover?

Jason Liu: We have four methods for deciding on the subjects we will cover: The Reporter’s editorial desk and the podcast team’s judgments on news and current events; audience feedback through Instagram and email; recent print reports; and feedback from colleagues.

Because our job is still to report, for me, creating a podcast is still about reporting the news. The difference is the format: using sound and various narrative techniques to create different connections.

There are three key points for us when we are choosing what topics we will cover. The first question is always “Why now?” Why do we cover a certain subject when we do? This might be the algal reef issues of Taiwan, what is happening in Thailand, the student movement, these are news stories, and we need to establish how we will use sound to present these issues.

The second question is “Why does it matter to everyone?” There are many stories in the world, and we cannot do all of them. As a public media outlet funded by donations, we want to create value, so we have to judge how strong the topic is, how it relates to our audience, or whether we can find relevant perspectives or connections in order to present it. For example, when we cover stories about stray animals, gay rights parades, transgender people, and political victims’ families, we will choose the most relevant connection points for the public.

The third question is “Why us?,” that is, “Why are we doing this topic?” Because many subjects are being covered by different outlets or being covered at the same time, we ask “What will we do that is different from the others? Can we do things that others cannot?” If we can, we will. It’s about expressing our unique value.

Interview Recording

Q: What equipment do you use when recording indoors and outdoors?

Lan Wanchen: When we go out for interviews, we will choose relatively light and functional equipment that meets our needs, and we decide which microphone to use according to the requirements of the occasion. The recorder we use most often is a Zoom H6, which can connect four external microphones, and there is also a relatively large radio connector.

When recording indoors, the Zoom H6 can work in an office with a relatively open space. Sometimes I go to a more enclosed and sound-proofed recording studio to record. We also often use RØDE’s Caster Pro, which has a four-track microphone and can also be connected to Bluetooth and audio cables.

Q: How do you choose the timing when going out for an interview? What kind of sound material is recorded to make the story sound more real?

Jason Liu: First, we look at the scene, and figure out where the interaction is going to take place and who is going to be the main speaker. If we are at an event, for example, we establish where the stage is, where the host is, and make sure we understand the entire venue. Once we’ve established that, the recorder will be turned on. We tape section by section to make sure that the recording is successful.

In one recent series, for example, Go Home with ABAO, a journalist for The Reporter traveled to Taitung, a city on the coast, to interview the Indigenous singer ABAO, who won Taiwan’s 2020 Golden Melody Award. At the beginning of the first episode, there was the sound of seawater, letting listeners know that we had come to eastern Taiwan, and then we recorded the sounds of aboriginal tribal children playing, so it would sound as if the audience were right there with us.

Jason Liu: At a news scene, critical moments will not happen a second time. In most cases, we will have the recorder ready, after determining who the subject is, and where the segment will be recorded, and then we will listen to it all again after we get back to the office.

Sometimes your judgment on the scene is not necessarily the best. After the interview, you have to leave the spot to listen to the recording from the audience’s perspective, which gives you a new understanding.

After listening, we will judge which content is good, but sometimes it’s sound quality is not necessarily the best, and then there will be a dilemma. Sound quality is the first consideration, but we are also a news podcast. If the content can convey the context of the scene, we have to choose between these two standards. It’s a struggle every time.

Q: Intimacy is one of the key characteristics of podcasting. How do you convey it?

Lan Wanchen: Jason will do a lot of homework before the official recording, reading news reports or materials related to the topic, interviewing relevant people to ask their opinions, and developing a certain understanding of the topic or person to be interviewed. Jason also has a preliminary interview with the guests, so that they can develop a sense of trust in us. Before recording, we explain the process with the guests, including what can be adjusted after the recording, and what topics the guests might want to explore more during the recording. The guests are mentally prepared so that they can tell their story. After post-production, we will ask the interviewee if we need to make any adjustments to the recording, for example, if anything sensitive was covered.

Jason Liu: I need to do a lot of work to host the show well. I remember that when I recorded the last episode of the first season, I recorded it three times by myself. When I recorded the third time, I knew where I was stuck: I realized that if I can’t speak from the heart, I can’t host a good show.

Most of the guests we invite are podcast amateurs, and the topics discussed are often sensitive, and very personal. I treat the guests like I would like to be treated myself, and I want people to be able to talk at ease. Wanchen mentioned the pre-preparation I do to reassure the other party, telling them “I only want to hear what you want to say,” then letting them say it. Actually, part of my role as the host is to add context for the audience to understand. To make it easier for the guest to concentrate on thinking about what they want to convey, I will add other things. This helps the relationship between me as the host and the guest.

Post-Production

Q: How do you write a script, sequence the material, and structure the program?

Jason Liu: Writing a script takes a long time for me: it’s more difficult than writing an article. One thing I try to bear in mind is the weight of the interviewee’s voice, making sure that the information and emotion involved in what they are saying is conveyed to the audience.

For example, for one story we did, at the end of 2020 about three groups of ordinary people and how they — and their industries — fared throughout the pandemic, we had one narrator who was a pilot, another was a Hong Konger seeking asylum in Taiwan. Why are their stories important? What is their job like? What background information does the audience need to have to understand what they are saying?

These are the pieces of information I need to fill in when writing the script.

There were three narrators in that episode, and each had a different style, rhythm, and the story content was different for each. You need to pull these strands together in the same episode so that everyone can hear the emotions they feel from the beginning to the end, and so the finished product is smooth. Added to that, is the speed and rhythm of the host’s narrative, which you need to consider when writing the script, what adjectives and nouns are used, and the density of the words. All this works to ensure the integrity of the story that you want to convey.

Recording an episode of The Real Story. Photo courtesy of Jason Liu and Lan Wanchen

Q: Each episode has a different soundtrack. How do you choose them?

Lan Wanchen: It is also very difficult to pick suitable music. First of all, I think it is very important to deal with the blank space of the live sound or the blank part of the discussion. You have to ask yourself, does this part require music, how tightly does it need to be edited, and how much background noise should be left in? I used to be a broadcaster, where clean sound quality and no gaps were the gold standard, but Jason told me that when he is doing an interview, the few seconds where he pauses in the middle of an interview actually show emotion. So I bear that in mind when I make the soundtrack, making sure I pay attention to this part and think about which areas will be more emotional if left silent, and which areas will be more emotional after adding music.

Sometimes I might listen to 20 or 30 pieces of music and not find something suitable. The next day I’ll search for different keywords, or listen to other people’s programs to hear similar themes or tones. Now when I hear good music, I think “that might be suitable for us,” so I will save it, like a squirrel storing food.

Q: What do you bear in mind when writing the copy of a single episode?

Jason Liu: As a media outlet, The Reporter hopes that engagement will be as high as possible and copywriting is a bridge. Careful listeners will notice that the tone of the copy of The Real Story will be younger and more lively than those for The Reporter, because the audience of the podcast is about five to 10 years younger than the readers of our text reports, so we use slightly different language to talk to the audience.

Listener interaction

Q: What do you know about the audience of the show, and how do you enhance audience participation?

Lan Wanchen: We use the data analysis and audience profile information provided by the hosting and playback platforms. The Real Story has a relatively high percentage of listeners on Spotify, which provides great data. Audience interaction on social media is also important. We know that a number of our listeners on Instagram are college students, even senior high school students, and some are older office workers.

We also held two audience meetings last year to share the content of the programs we have done and our production experience, where we asked listeners to give their feedback. We used the recording clips from that meeting for an End of the Year Truth Special, hoping to make the audience feel that everything they shared with us was heard and will become a part of our program.

Jason Liu: We have now received between 6,000 and 7,000 pieces of feedback, including comments on Apple’s podcast platform, private messages on social media, and from the questionnaires we distributed. We asked many questions, including: “How long have you been listening to the show?” “What else do you listen to besides us?” “Why do you listen to our show?” “Which episode is your favorite?” We let the audience tell us who they are and what they want because interaction is something we emphasize very much. We treat podcasting as part of our news output, and the news media needs to find itself and connect with readers in a digital age where everyone uses social media.

Q: What impact did the podcast have on The Reporter?

Jason Liu: Firstly, when we started broadcasting The Real Story last year, many people got to know The Reporter that way, which alleviated the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fundraising and allowed us to reach last year’s fundraising goal. In addition to many one-off donations, the number of new regular donations to The Reporter since we launched the podcast accounts for somewhere between a third to half of the total.

Podcasts also provide you with more choices and help us reach more people, demographic groups such as mothers, takeaway workers, people working the night shift, teachers and students, listeners overseas, and those in rural areas, etc. In the past, they were not readers of our long-form stories, but they can all listen to podcasts.

The Real Story is not just a podcast. Behind it is the brand, and in a way, the whole team of The Reporter has spent five years working towards it. But as a sub-brand, it has achieved good initial results. We never imagined we’d be able to reach the audience we do.

Personal Experience

Q: Which podcast programs or single episodes have inspired you?

Lan Wanchen: I recently listened to Fan Qifei’s podcast The Story Teller, and was amazed by how they deal with sound engineering.

Jason Liu: I have listened to This American Life and Story FM for a long time. It is not easy to tell stories well, fully, and clearly through sound narration, but these two do it well, especially on This American Life, which has a lot of resources, and where the team does a lot of interviews and uses a whole episode to explain a concept carefully through good editing. When I listened to these two podcasts, at first I was envious, thinking how could we learn from them when we only have two people to tell the story and express the emotions we want to express?

But because I used to do international reporting, I originally used podcasts as a source of information. For example, with the BBC’s HARDtalk, I will listen to how the host asks difficult questions, learn how to deal with conflicting positions, and how the two sides maintain the spark of the interview.

Additional Resources

A Global Tour of Top Investigative Podcasts: The 2020 Edition

7 Things I Learned Producing My First Investigative Podcast

The Power of Emotion: How to Connect With Investigative Podcast Listeners

This story has been translated and adapted from the original Chinese. The original story can be read here. Chen Hengyi is a freelance writer and Chinese podcast observer.