How to Track Chinese Business Around the World

From Shanghai to Senegal: Whether it is a small business or a major corporation, Chinese business are operating around the world.

As Chinese investments reach the furthest corners of the globe, journalists around the world are taking serious notice.

Last week at the Asian Investigative Journalism Conference in Seoul, the interest in Chinese global business operations was underscored. A packed room of reporters gathered to hear tips from senior journalists from The Guardian, The New York Times and the South China Morning Post.

The journalists offered advice on tracking Chinese business in Africa, Europe and Southeast Asia. They gave insider knowledge about how to investigate Chinese businesses, and shared forensic tools and resources to help reporters follow the money.

Know Your Subject

Maria Abi-Habib of the New York Times uncovered the story behind the transfer of a Sri Lankan port to China under heavy pressure of debt. Before assigned to the story, Abi-Habib had never been to Sri Lanka and didn’t have any experience reporting on it. To investigate the deal between China and Sri Lanka, she “built a human database” of her own, beginning with studying thousands of pages of articles related to the issue, and taking particular advantage of Sri Lanka’s local media. While reading, Abi-Habib took down the names of those who may have been involved and asked for meetings with almost all of them, leading to key sources and documentary evidence. Here are her top tips to journalists:

Read extensively and exhaustively: Scour every single page of every single document to find little red flags; make good use of local media’s reporting.

Meet as many people as possible: You will be surprised by how many people know about one another in a small country like Sri Lanka.

Cultivate “small fish” sources: Mid-level officials and retired foreign officials are often good sources who have inside details and may lead you to even more valuable sources.

Avoid Generalization

Lily Kuo of The Guardian specializes in China’s Belt and Road Projects (which include overland corridors and maritime shipping lanes) in Africa. She noted the importance of understanding the issues from the ground in order to rid the subject of of bias and generalizations.

Using her own experiences as examples, she summed up three approaches to covering the topic of China and Africa, which are also helpful when examining Chinese businesses abroad in general:

Look at the range of Chinese engagement. It’s not all about big companies but many small and private entrepreneurs, as well.

Realize that there are other levels of globalization as opposed to an entirely a top-down approach of the Chinese state as widely perceived by public.

Make sure to look at the ground-level impact on the locals. This is how you can find the most interesting stories which will help explain what Chinese investments or expansion mean to the countries involved.

Report Globally

Swiss-based journalist and media consultant Patrick Boehler gave an overview of the heated topic of Chinese investment and influence in Europe, and reminded the audience that journalists need to take their reporting global. For journalists who often find it difficult to trace or ask questions about Chinese investment projects, Boehler listed some of the frequent red flags to look out for.

The increasing amount of research by European Union think tanks and newsrooms on China have also made covering Chinese investments an easier task for journalists, and Boehler included a list of sources where journalists can find some of that research.

Use Open Sources

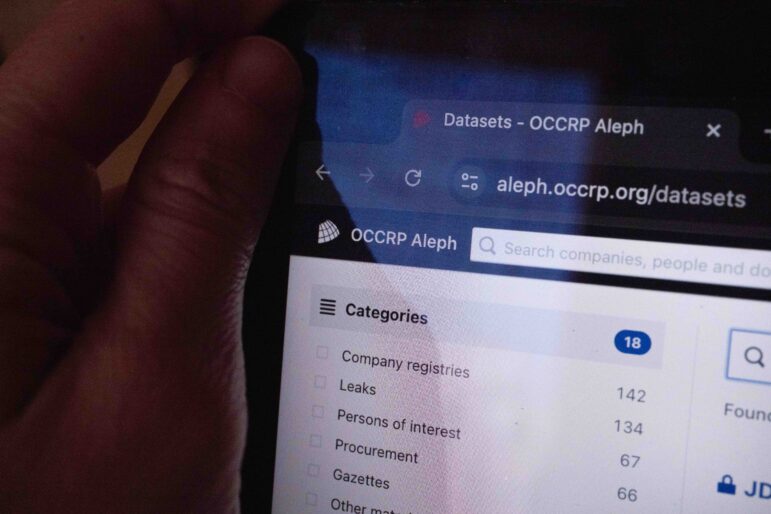

Karen Zhang from the South China Morning Post shared comprehensive public sources where journalists can find and trace Chinese businesses in mainland China and Hong Kong. Her tips include everything from the official databases of governments or public institutions and commercial websites as well as a wide range of Chinese social media and other sources, such as the Panama Papers.

Going to the Source: A comprehensive resource to help trace Chinese businesses, from Karen Zhang’s presentation.

When tracing the money and people behind a dubious business, one of the most frequent issues for foreign journalists may be deciphering Chinese names. Check out Zhang’s useful tips for verifying identities as well as the example of her discovery of the fugitive Malaysian businessman Jho Low’s companies in Hong Kong.

Happy digging!

Siran Liang is Chinese editor at GIJN, where she oversees its Chinese website and daily feeds on Weibo, WeChat and Twitter. She has a master’s in journalism and media studies from the University of Hong Kong. Before joining GIJN, she interned for the Nepali Times, where she covered the country’s reconstruction after the 2015 earthquake, as well as the blockade by India during that time.

Siran Liang is Chinese editor at GIJN, where she oversees its Chinese website and daily feeds on Weibo, WeChat and Twitter. She has a master’s in journalism and media studies from the University of Hong Kong. Before joining GIJN, she interned for the Nepali Times, where she covered the country’s reconstruction after the 2015 earthquake, as well as the blockade by India during that time.