Want to Track the Pentagon’s Funding? Here’s How You Can Follow the Money

In the 2017 financial year, the US Department of Defense alone spent about $590 billion, according to data from the Congressional Budget Office in Washington, DC. Even veteran journalists who cover the US government extensively can find themselves stumped.

In the 2017 financial year, the US Department of Defense alone spent about $590 billion, according to data from the Congressional Budget Office in Washington, DC. Even veteran journalists who cover the US government extensively can find themselves stumped.

“It was like an acid flashback getting your email,” said Steve Fainaru, winner of the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting. “This was a huge issue for us. We couldn’t get these contracts.”

His reporting from Iraq shows millions in cost overruns for security contractors.

Since that series, new databases have been posted online that can help those looking to follow the money wherever it flows, including making it easier to trace contracts from companies in a specific country or servicing a particular area.

Knowing What to Look For

But first things first: Before you get to the contracts, it’s good to look up a little information on a contractor you are interested in whenever possible. This information — like the official name, address, any red flags, and a DUNS number (a numeric identifier by Dun & Bradstreet) — can help make sure that when you do find a contract, it’s with the company you think it’s with. Not surprisingly, a lot of government contractors choose fairly generic names so it’s easy to get confused.

Backgrounding US Contractors With SAM

Since 2012, the System for Award Management has been the primary supplier database for the US federal government, bringing together procurement information formerly housed in nine different places, including the Central Contractor Registration.

“It’s the registry of people that are eligible for government contracts,” explained Scott Amey, general counsel at the Project on Government Oversight (POGO). “You can look up other information in there as well on past things that are in their archives and you can look up contractors that have been suspended or debarred.”

Amey has been involved in POGO investigations into everything from environmental disaster and emergency response to defense lobbyists.

“You name it, we’ve done it,” he said, and SAM is often the best starting point for an investigation.

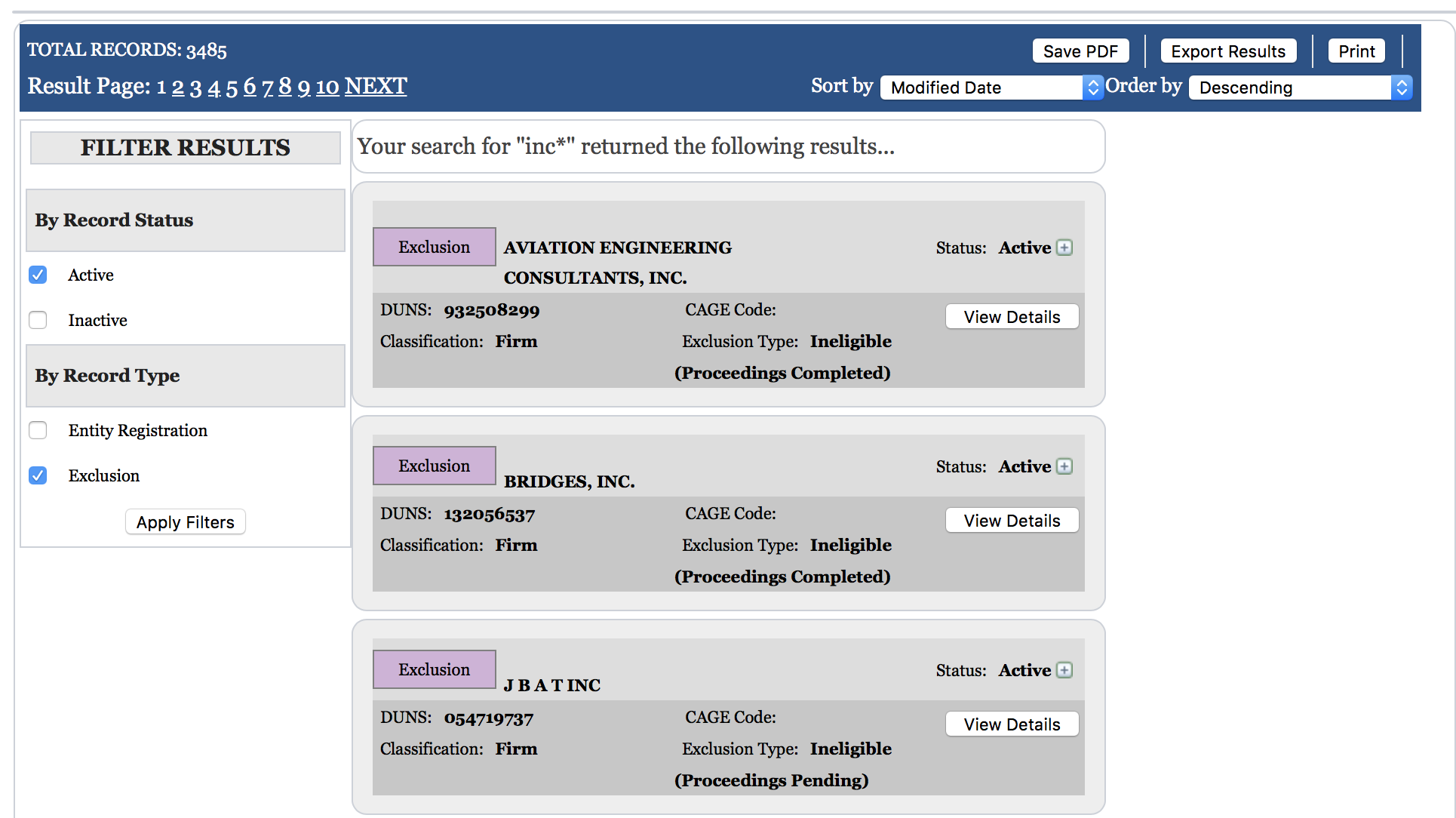

While it won’t give you details on specific contracts, the site makes it easy to search through registered federal government vendors, get details like DUNS Commercial and Government Entity (CAGE) codes, and see if a given company is under any active or resolved exclusions.

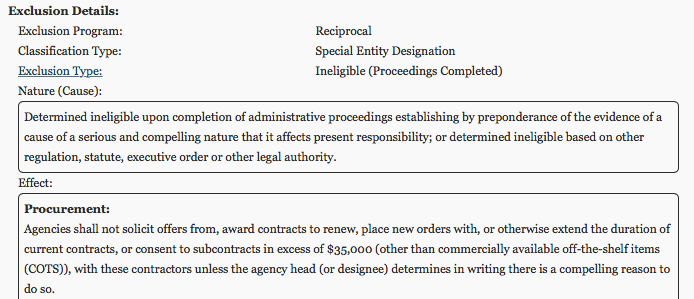

If they are, it often provides details about why they are excluded from the procurement process for given agencies, which can be useful context:

This kind of information has been useful in digging into contractors that continue to win big government contracts despite troubling settlements. For example, SAM was used by POGO to uncover the name of secretive Department of Defense contractors that had violated restrictions on human trafficking.

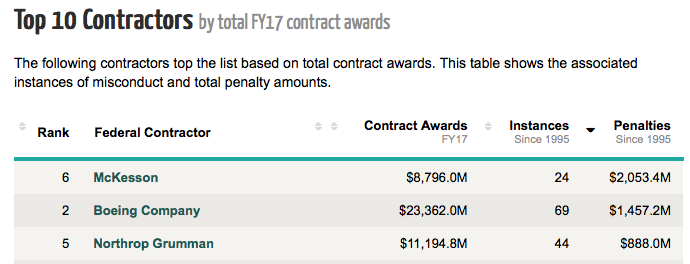

POGO also has its own database that can be helpful when digging into contractors of all kinds. Called ContractorMisconduct, the database draws from FOIA documents, press releases, court proceedings and more to track misconduct by contractors dating back to 1995.

The database totals how many contracts a given company has won, the number of instances of alleged or actual misconduct, and the amount paid in penalties (though this is often a low count due to how hidden penalties can be).

Things to take note of in these databases are the different spellings of contractors (often times entities will have different spellings for an organization at different times, even something as simple as differently placed punctuation); the DUNS and CAGE codes; and any exclusions.

Exclusions identify contractors that are prohibited from receiving federal contracts, although often these are limited to certain types of contracts or subcontracts or assistance and benefits. They are also known as “suspensions” or “debarments.”

Finding Specific Contracts

Armed with a little more background information, there are several databases to take your search next.

FBO.gov

FBO.gov (which, oddly, has a header image that touts the non-working URL FedBizOpps.gov) is usually a good next stop after SAM, according to Amey.

“From there you can look up the solicitations that have been advertised,” he said. “There are some limits because not everything gets thrown into FBO.gov, and obviously things that involve the Intelligence Community and black programs aren’t in there, because they’re not going to advertise those ever.”

But there still can be a wealth of information on a variety of contracts and subcontracts, often with useful attachments and other related materials.

“FBO is, for me, the most interesting database,” said Margot Williams, research editor at The Intercept. She said the site becomes even more useful if you sign up for a (free) account. “You can get a list of interested vendors that you can’t see without logging in. And you can see all the questions and answers vendors have sent anonymously to the agency. That gives you an idea of who might have bid on the contract.”

The interested vendor list also often includes contact information, which is a useful resource if you want to call up losing bidders for more context or background on a bid — particularly if there’s a chance they felt the process was not fair.

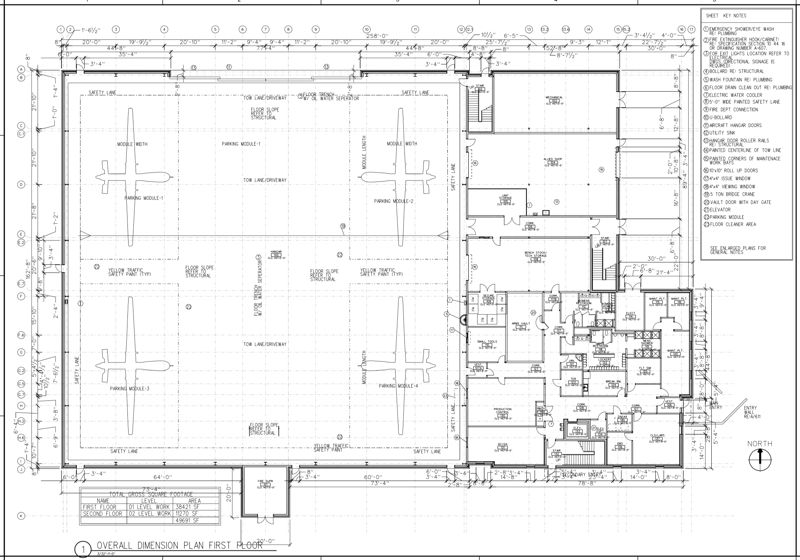

But even without logging in, there can be a lot of useful information. For example, individuals looking for more details on a drone airport in El Paso could dig up hundreds of pages of detailed diagrams showing the layout of the airport:

“There’s a lot of stuff in there that may be helpful,” said Amey. “You can actually look at the solicitation notice, so you’ll get a statement of work, how they think they’re going to award it, what they’re asking the contractor to do. Sometimes that ends up being a laundry list of different things that get amended; sometimes you can see the questions that were asked by the contractors. You get to see if it’s kind of sole source even from the start because sometimes they’ll list it there even if they’re directing it and it’s going to be a sole source contract.”

The site does not, however, post the final contracts.

“It’s still the case that they don’t post the contracts anywhere, because the contractors get to weigh in on what gets to get released,” said Williams.

Also, not every award makes it to FBO… or stays there. The site often cycles off solicitations over 365 days old. Other databases can help you peer further into the past.

USASpending.gov

If you can’t find what you’re looking for on FBO, check out USASpending.gov, which offers a simple contract keyword search and a more powerful advanced government award search.

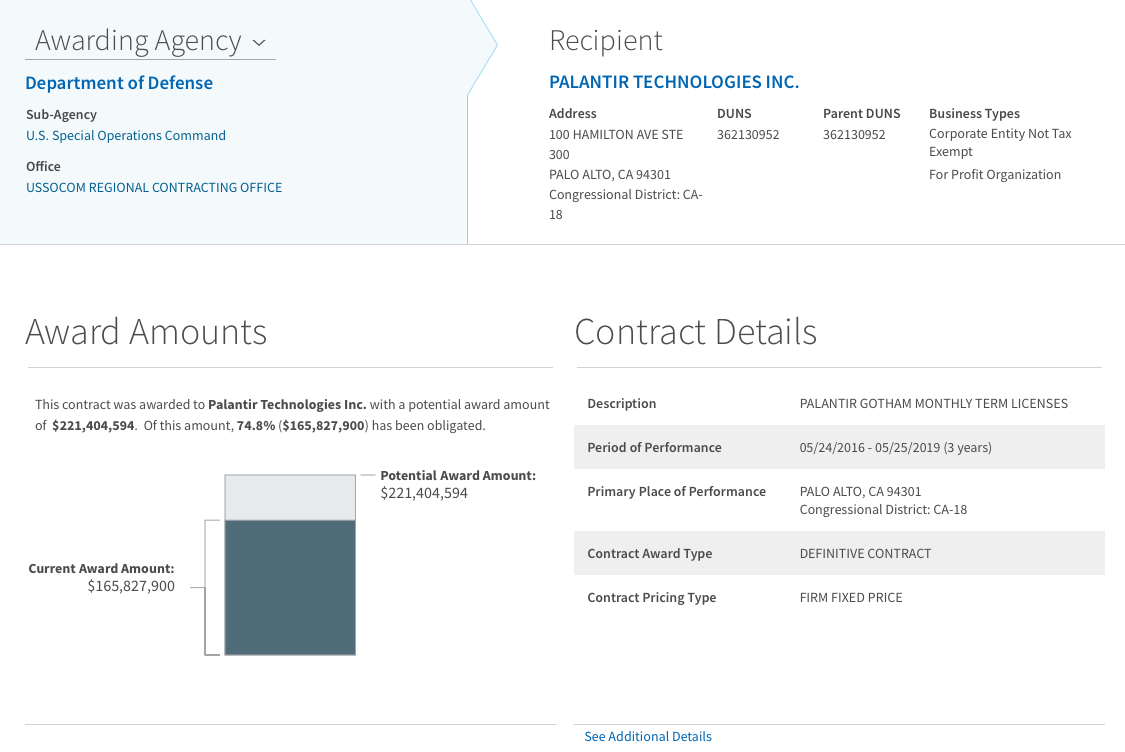

Government spending data has never looked so good:

While these results don’t return as much detailed documentation as FBO, they do include a variety of easily parsable information on the bid, as well as details on the agency, sub-agency, and office that awarded the contract — crucial information for crafting a specific FOIA request for the contract itself if it’s needed.

They also include details on modifications to contracts, the amounts those modifications were for, and a summary of why the modification occurred.

It also lets you dig into sub-contracts, which are generally not available in other databases.

“It does not have all subcontracts. I wouldn’t do analysis on it, but it’s the only way to find some of those subcontracts,” said Williams.

For those who aren’t afraid to get their hands dirty with a little code, there’s also the option to bulk download data or access it programatically.

FPDS

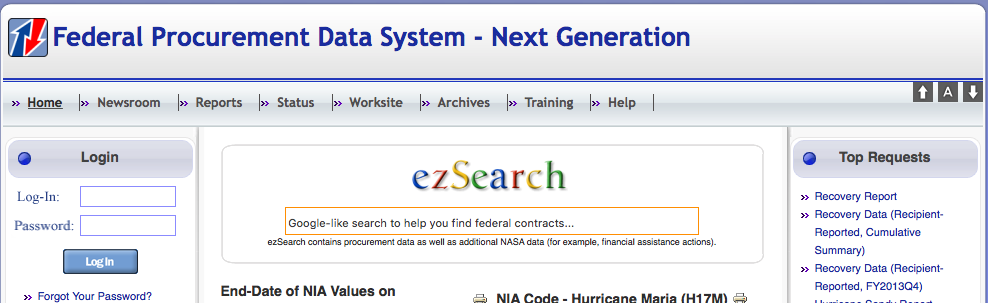

The Federal Procurement Data System is another useful tool. If its aesthetic is showing its age, that does not stop the site from providing a wealth of information, from Award ID, type, and amount to contracting office and details on modifications.

Of FPDS and USASpending, Williams said the former was more comprehensive with the exception of sub-contractors.

USASpending and FPDS both contain a wealth of information, but it’s important to note that they get data after a contract is awarded — FBO includes contracts that are still up for grabs, in addition to having more detailed information on the contract opportunities.

USASpending and FPDS are very useful for tracking the progress after the award has been granted.

“You want to go there to start seeing how much money’s pouring into it. Have they amended the contract, has it been modified, has more money added to it?” said Amey. “Are they adding things, are they adding to it as far as time frames go?”

Some things to look for that might be of interest are contracts awarded to companies in a foreign country or that take place in an interesting location.

“I’m often looking to see what contracts are going to be done in Guantanamo, so you can see when they’re going to be building a new facility there or expanding a facility,” said Williams.

DoD Contract Announcements

If you’re interested in recently awarded contracts, the US Defense Department has other good resources specific to defense contracts: At 5 p.m. EST each day they list awards of over $7 million, including some details on what the contracts were for, the component overseeing the contract, and the contract ID number.

You can sign up to get these updates emailed to you on a daily basis.

GSA eLibrary

Another resource to look for information on both contracts and contractors is the GSA eLibrary.

This provides a look at pre-negotiated contracts that agencies can choose to leverage with various vendors, letting agency personnel (and you) see a set price list various vendors offer by searching through keywords or vendor information.

“You can see what the statement of work is, what the [vendor] is providing … and you can also see what the rate or the ceiling price is for what the hourly rate is for services,” said Amey.

Good Jobs First Violation Tracker

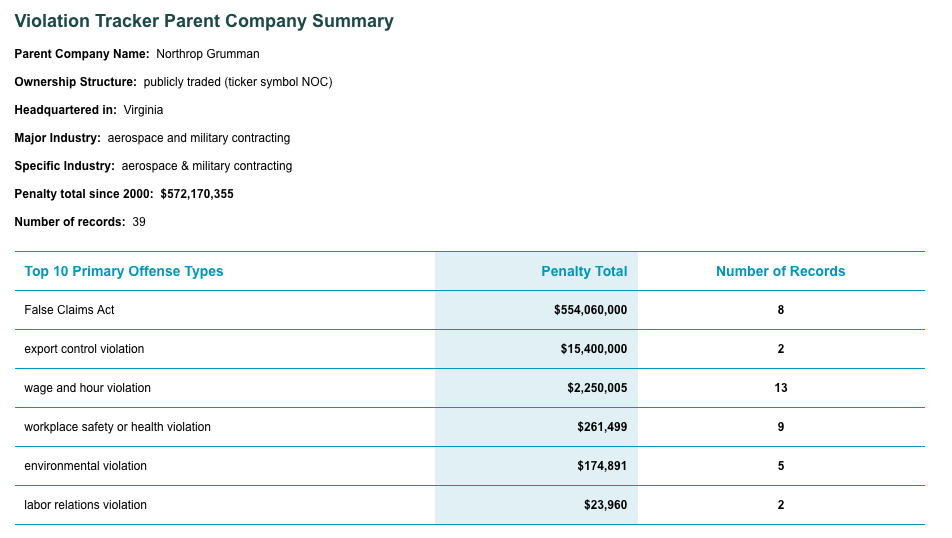

Another useful resource when digging into a specific contractor is Good Jobs First’s Violation Tracker, which tracks a variety of violations such as False Claims Act issues, export control violations, and environmental problems.

Good Old-Fashioned Internet Sleuthing

Once you have as much information on the contract as you can get, now it’s time to turn to actually digging up the contract if you still need it. It can be surprisingly effective to just type a contract number into Google.

There’s also a few advanced search techniques that can net quality results.

First, just limit your results to only official domains. On Google and many other search engines, you can add site:.mil and site:.gov to a search bar to restrict it to just those top level domains (or substitute in a particular agency’s website). I’ve found this particularly powerful when coupled with another advanced search limiter: filetype:.pdf and filetype:.docx. Strangely enough, cleverly limiting your results can help find gems more quickly.

How to FOIA US Government Contracts

Sometimes, the above information coupled with solid human sourcing might be enough.

“The stories that we ended up doing, if you go back and look at them, there weren’t that many of them that were really about the contracts,” said Fainaru. “There’s different ways you can get at that stuff. If you’re looking for the numbers, usually they’ll show up on somebody’s budget or in a report.”

Going Beyond Google

But if you need to dig deeper, a well-worded and placed FOIA request can often dislodge a fuller look at how the agreement is supposed to work, especially if you’re relying on a USASpending or FPDS entry or a DoD announcement.

“Those systems are summary data only so they kind of just give you a list of items and some boxes are checked, some aren’t checked,” said Amey.

Once you have that contract number, Googling for it can sometimes pull it up or provide enough to ask a source (sometimes even in their media relations department) for a copy of the contract, but if that does not yield results its time to turn to a FOIA request.

FOIA-ing the Fine Print

In your FOIA request, you’ll want to make sure you include the contract number, the award ID, the date of the contract, and either submit the request to the office that awarded the contract or else note the office in the letter so that the agency’s FOIA personnel make sure to task it to the right place. Here’s a good example of a request filed by Curtis Waltman.

Requesters should also consider asking for related “show cause” or “cure” notices, which can often signal red flags. A cure notice is when a contracting officer has concerns about a contract, while a “show cause” notice indicates that a contract could potentially be removed from a vendor.

Read more tips on FOIAing the Department of Defense with our interview of Jim Hogan, the DoD’s Chief of FOIA policy. If you’re a member of Investigative Reporters and Editors, they have a variety of useful tipsheets, particularly those from Tony Capaccio, a legendary reporter often on the defense beat. You can also check out MuckRock’s interviews with FOIA experts for more tips.

Don’t forget to also look into audits and other after-the-fact documentation regarding a contract you’re interested in. (Here’s an example request for Afghanistan police and military uniform contract audits). There’s also the excellent Oversight.Garden for public Inspector General reports to explore past problems with a specific contract, vendor or topic.

A modified version of this post originally ran on MuckRock.

Michael Morisy is the co-founder and chief executive of MuckRock. He was previously an editor at the Boston Globe, where he launched the paper’s technology vertical BetaBoston. He is currently a 2018-19 nonresidential fellow at Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri. He was a 2014-15 John S Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University and a 2012-13 Edmond J Safra Center for Ethics Network Fellow at Harvard University. He graduated in 2007 from Cornell University with a degree in English. He can be reached at michael@muckrock.com.

Michael Morisy is the co-founder and chief executive of MuckRock. He was previously an editor at the Boston Globe, where he launched the paper’s technology vertical BetaBoston. He is currently a 2018-19 nonresidential fellow at Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri. He was a 2014-15 John S Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford University and a 2012-13 Edmond J Safra Center for Ethics Network Fellow at Harvard University. He graduated in 2007 from Cornell University with a degree in English. He can be reached at michael@muckrock.com.