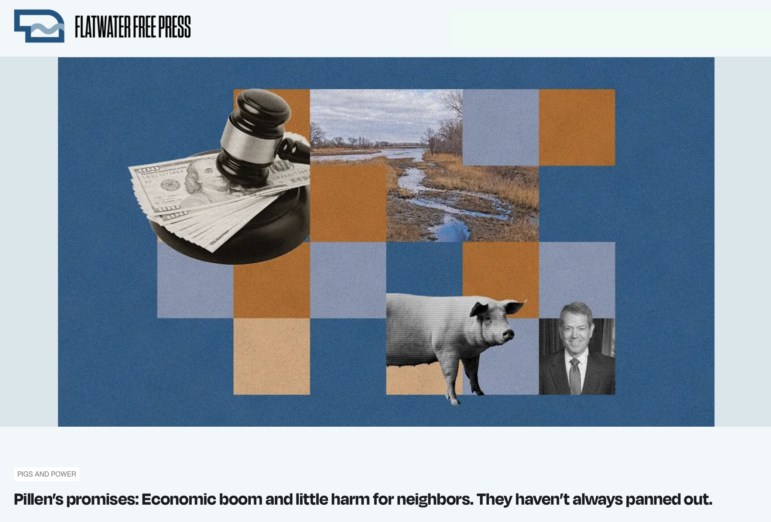

A file photo of industrial hog farm. Image: Shutterstock

Uncovering the Hidden Environmental Impact of an Industrial-scale Hog Farm

Yanqi Xu is an investigative reporter for the Flatwater Free Press. She’s written extensively about the state’s nitrate contamination. Her partner in the collaboration, Sky Chadde, is a senior reporter at Investigate Midwest, which covers the agriculture industry.

An investigation by Xu and Chadde exposed how a hog-farming empire owned by Nebraska Governor Jim Pillen polluted groundwater with a cancer-linked chemical, revealing deep-rooted issues of political influence and regulatory neglect.

The three-part series earned first place for Outstanding Explanatory Reporting, Small, in the Society of Environmental Journalists’ 23rd Annual Awards for Reporting on the Environment. Judges called it “a masterful job of meticulous investigative reporting” and praised it as “an admirable model of what environmental reporting should strive to achieve.”

In the wake of her reporting, Pillen dismissed Xu based on her nationality, prompting SEJ to issue a supporting statement and the SEJournal’s WatchDog Opinion to write a column condemning his response.

SEJournal Online recently interviewed Xu by email about the project. Here’s the conversation, lightly edited for clarity and style.

(Editor’s Note: Pillen did not respond to multiple interview requests from Flatwater Free Press and Investigate Midwest when asked about his hog operations. Sarah Pillen, the governor’s daughter and CEO of Pillen Family Farms, did provide a statement, saying that the family’s company “…always placed a strong commitment on being positive environmental stewards of the land.”)

SEJournal: How did you get your winning story idea?

Yanqi Xu of the Flatwater Free Press. Image: Screenshot, LinkedIn

Yanqi Xu: We decided to closely examine the Nebraska governor’s role at the crossroads of being the state’s biggest hog producer and running an agricultural state. Gov. Jim Pillen was known for recovering a fumble against a big college football rival in the 1970s. In 2022, he came to prominence as Gov. Pete Ricketts’ hand-picked successor, but little was known about how Pillen grew his business or its impact on the state until our project.

SEJ: What was the biggest challenge in reporting the pieces and how did you solve that challenge?

YX: Though we knew Pillen’s family operated the biggest hog producer in the state, there wasn’t a publicly available list of all hog farms owned by his family. We made several records requests, cross-referenced with other agency records and finally figured out a way to effectively ask for the list from the state environmental agency.

SEJ: What most surprised you about your findings?

YX: The hog farms built by the governor had a far deeper impact in many different ways than we had anticipated, including the small towns’ economies, water quality, and the living conditions of neighbors. Some neighbors told us the proposals to build hog farms divided the town.

SEJ: How did you decide to tell the story and why?

YX: We decided to write a multipart series that included both the history and present-day conditions of the hog empire Pillen built over decades. For historical context, we relied a lot on public meeting minutes, court documents, and newspaper clips from the past, as well as records collected by the state environmental agency. We also interviewed neighbors who had lived close to some Pillen hog farms for decades, asking them about their experiences.

SEJ: Does the issue covered in your story have disproportional impact on people of low income, or people with a particular ethnic or racial background? What efforts, if any, did you make to include perspectives of people who may feel that journalists have left them out of public conversation over the years?

YX: Those who said they were impacted by the hog farms are typically farm families who didn’t own big farms. We felt those people had their voices heard when the fights over the hog farms were very public, but our stories added to the public’s understanding of what is happening today.

SEJ: What would you do differently now, if anything, in reporting or telling the story and why?

YX: Stories centered around people are often the most compelling. Starting with areas where these hog farms have a strong presence from the beginning would have made the stories more powerful. We only identified these areas later in the reporting and had limited time to build sources in those communities. And it takes time to gain trust from community members who felt their voices had been unheard for a long time. At the same time, it’s important to note the nuanced nature of these confinement projects and why some residents were supportive of them.

SEJ: What lessons have you learned from your project?

YX: Sources with institutional knowledge and those who’ve been through the early days of coming up with livestock regulations or involved in economic development were incredibly valuable to the story. They provide good perspectives on why and how some hog farms are able to come into town, and helped us contextualize how things evolved over time.

SEJ: What practical advice would you give to other reporters pursuing similar projects, including any specific techniques or tools you used and could tell us more about?

YX: It’s important to consult sources who’ve been to animal confinements and know how waste is managed. We have to do our due diligence and make sure we’re accurately describing the scope and timeline of a spill, for example.

Xu’s investigative series on Gov. Jim Pillen’s hog-farm empire was recognized at Society of Environmental Journalists’ 23rd Annual Awards for Reporting on the Environment. Image: Screenshot, Flatwater Free Press

SEJ: Could you characterize the resources that went into producing your prizewinning reporting? Did you receive any grants or fellowships to support it?

YX: The organization ProJourn offered legal consulting resources, and we consulted lawyers throughout the reporting period. The whole project took several months and we built more sources in the months when we took a hiatus from the story.

SEJ: Is there anything else you would like to share about this story or environmental journalism that wasn’t captured above?

YX: Science can be pretty messy! This reporting taught me a lesson to be transparent about what we know and don’t know. Don’t be afraid to withhold information that could benefit the public, but also never pretend we know more than we do — always rely on the reporting.

Editor’s Note: This interview was originally published by SEJournal and is republished here with permission. It has been lightly edited.

![]() SEJournal Online is the weekly digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

SEJournal Online is the weekly digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists.