Image: Courtesy of the BBC

Uncovering Syria’s Stolen Children

The fall of Bashar al-Assad in late 2024 reverberated through Syria like a proverbial earthquake, as his decades-old regime of dictatorship, oppression, and secrecy melted away almost overnight. For both local and foreign journalists, Assad’s ouster also presented a rare opportunity for accountability reporting, a chance to pursue stories of wrongdoing by his regime that had been difficult, if not impossible while he was still in power.

One of the most shocking accusations against the regime involved accounts of the abduction of hundreds of Syrian children of political detainees by officials from Assad’s government and the complicity of children’s charities operating in the country.

Investigators from the BBC, The Observer, Der Spiegel, Trouw, Lighthouse Reports, SIRAJ, and Women Who Won the War joined forces to report from the ground, analyze hundreds of documents, and find out what really happened to these children. What we found revealed how the Assad regime used a global childcare charity to aid the disappearance of children. In addition to the investigative partners, other Syrian outlets, Sowt and Al-Jumhouriya, joined the collaboration to publish longform text and audio pieces.

Documenting the Big Picture

“In February [2025], I traveled to Syria for the first time in more than a decade,” explains Bashar Deeb, an open source investigative journalist with Lighthouse Reports on this project. “I had long given up hope of seeing my family in Syria, let alone working in my country as a professional journalist.”

“Within days of al-Assad’s ouster, relatives of missing children who were detained with their families started speaking out for the first time about the role of orphanages in taking their children,” Deeb notes. “Like many Syrians, I was horrified for these parents and their children and couldn’t shake the idea of these young infants removed from their parents by a cold state bureaucracy.”

The Lighthouse team began building a database of as many of the missing children as possible. Eventually, with the contribution of their reporting partner organizations, the group obtained thousands of official documents from the Syrian Air Force Intelligence, as well as the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour and local orphanages, including confidential correspondence, detainee lists, referral files, log books, and detailed case records. “Using all the documents we gathered along with open source information, we built a comprehensive database of verified children that were sent to orphanages following the arrest of their parents that included more than 320 children,” Deeb notes.

Understanding the System and Victims

Meanwhile, the BBC’s documentary team, who had been following leads for months, arrived to film in Syria in May 2025. Haya Al Badarneh, a London-based BBC producer, had begun investigating social media posts about missing children as far back as the summer of 2023. In Syria, the BBC were able to meet with employees of an Austrian global childcare charity that was a key player within the state’s systematic disappearances of children: SOS Children’s Villages International. Lynzy Billing had been in Damascus after the fall of Assad, reporting for The Observer. She connected the team to further sources within SOS and shared documents from the Ministry of Social Affairs.

“It wasn’t easy to gain their trust,” notes Al Badarneh. “Even after the fall of Assad, many feared that remnants of the regime could still retaliate. Others, we suspected, didn’t want to admit their own complicity.” In all, Al Badarneh, BBC producer director Jess Kelly, and other journalists in the wider team spoke to 54 former or active SOS employees.

These sources detailed how the children were taken from prisons where their parents were being held by the authorities, often by the Air Force Intelligence, and then sent to SOS or other orphanages, with the cooperation of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labour. These employees were under strict orders not to photograph the children or talk to them about their families, and in some cases the children’s names were changed to prevent them from being found by their real families.

“After months of conversations with Al Badarneh, one SOS employee agreed to give us access to photos and details of the system used by the government and SOS to hold and hide the children in SOS Syria,” Kelly says. So, the BBC began reaching out to families whose children had been taken.

Layan, Muhammad, and Layla Ghbeis (left to right) upon their release, three years after being taken. Image: Courtesy of the BBC

“Among the cases that haunted us most was the Ghbeis family,” Kelly recounts. “Abdulrahman Ghbeis, then a Red Crescent worker in Ghouta, broke down in tears as he told us how he posted a photo on Facebook in 2015 celebrating the birth of his newborn son, Muhammad. He believes this post is what triggered the arrest by the Air Force Intelligence of eight members of his family including his nieces — eight-year-old Layla and four-year-old Layan — and his newborn son. The regime effectively used the children to psychologically abuse the parents. When the children were finally reunited with their parents in a prisoner swap with regime soldiers three years later, neither Layan nor Muhammad had any memory of their parents.”

Value of Collaboration

Lighthouse Reports had obtained several batches of government documents,” Kelly notes. “They had done amazing work cross-referencing the documents and were building a database of all the missing children with other partners, both international and Syrian.”

“There was a lot of misinformation online. The collaboration increased our capacity to verify the facts, notice patterns and get a proper grasp of on the numbers, names, and organizations involved,” she added. “Our aim was to publish the findings of this investigation on the same date as the rest of the outlets to help dispel some of the myths that had grown online, maximize impact, as well as minimizing the re-traumatization of parents and children who had been through so much already.”

Deeb agrees that collaboration strengthened everyone’s reporting. “None of this would have been possible without the partnership between Syrian and international journalists,” he says. “Our international colleagues brought new perspectives and sources to the table. While we analyzed documents collected in Syria, the BBC Eye team was on the ground in Damascus, Beirut, Austria, and Boston, following families searching for their children and looking for justice.”

“When one of us reached a dead end, another often found a new path or a related source. We constantly challenged each other’s blind spots and cross-checked every detail of our findings,” he explains. “The collaboration also helped us to be creative and flexible in reaching different audiences and considering different ways our journalism might contribute to accountability. This includes the al-Assad regime officials still at large, the new Syrian government which is struggling to respond to families’ demands for answers, and SOS Children Villages International, the massive international nonprofit that silently complied with the al-Assad regime’s abduction of children for years, taking in the largest number of children in our database.”

Impact and Accountability

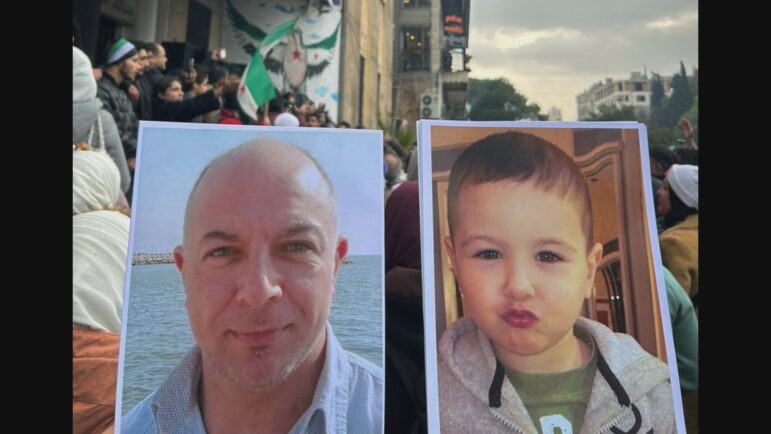

Posters of Reem al-Turjman’s missing husband, Osama, and son, Karim. Image: Courtesy of BBC

“It felt important to tell the story of a mother still looking for their child so that we could show the obstacles families still face while searching for missing children in Syria post-Assad,” Kelly says. “Reem al-Turjman’s story was chilling. In 2013 her husband left home with their two-year-old son, just to drop his friend home, and they never came back. Twelve years later we filmed her ongoing search for them, one of the most heartbreaking journeys I’ve followed in my career.”

“By the time we arrived in Syria, three separate official investigations were already underway,” Kelly says. “The newly formed Syrian government had launched its own inquiry, but it was staffed entirely by volunteers and barely funded. Months in, they hadn’t managed to reunite a single child with their family. Reem felt very alone and did not know where to turn.”

Two other separate investigations were being led by SOS Children’s Villages International, she added, but internal cooperation was very limited and the effort was being run by a Norwegian law firm that didn’t appear to plan on investigating on the ground in Syria. When al-Turjman visited the SOS Syria branch personally, and begged to see photos of the children, SOS refused for privacy and protection reasons and told her they would get back to her in six months.

The podcasts, articles, news videos, social media clips, and the documentary from the Syria’s Stolen Children project were published on the same day, targeting key stakeholders across diverse platforms. The BBC provided broad international visibility across Europe and the Middle East, while a featured investigation in The Observer ensured engagement with UK readers. In the primary donor countries for SOS Syria, reporting in Der Spiegel and Trouw directly reached the key audiences of the organization’s main funders.

To engage the most affected communities, Al-Jumhouriya provided the space for a compelling deep-dive longform report for Syrians. This was complemented by an Arabic podcast with Sowt, which utilized the intimacy of audio to center the voices of mothers and children. By leading with their own testimonies, the podcast edited and produced by Mais Katt (the editor of Women Who Won The War) and Saleem Salameh captured the profound emotional weight of forced separation and ensured the families remained at the heart of the narrative.

In response to the investigation, five different branches of SOS issued statements, expressing “horror” and “condemnation” about what had happened in their Syrian village. And within a few weeks, the SOS leadership in Austria issued an unequivocal apology for the first time and indicated that it would undertake systemic reform. The board chair of SOS International in Austria emailed all staff explaining the group planned to fast-track child searches and reunions, and to open up their tightly held data for reasonable review. The charity also announced that SOS Syria would be closed within three years and review all current directors and senior staff of SOS member associations worldwide for “political affiliations that could compromise neutrality.” A WhatsApp group was also set up by the reporting team for the families to ask any questions.

A few weeks after the joint publications, Lighthouse Reports and Women Who Won The War collaborated with Syrian civil society organizations to host a screening of the BBC Eye film, “Syria’s Stolen Children,” in Damascus attended by some of the family members. The subsequent panel discussion, featuring Katt, explored the stories of affected families and the responsibility of Syrian transitional authorities to uncover the truth, garnering significant media attention with coverage from multiple television channels. Reflecting on the event’s impact, Katt noted that “the gathering felt like the first time families of missing children and victims were truly being heard; in addition to the panel, they were extensively interviewed by numerous journalists and news crews, which significantly increased the pressure on authorities to investigate the issue.”

Following the BBC documentary’s screening in Syria, the Ministry of Social Affairs also met with families of missing children, including al-Turjman. The Ministry promised her that meetings would be arranged with the Ministers of Justice and Interior to advance accountability efforts.

The project also provided the victims — both children and parents — a better sense of the trauma each of them had endured. “For the Ghbeis family, it was the first time they heard the full extent of each other’s detention stories,” Kelly said. “It helped them heal some wounds and strengthen their relationships. The family’s relatives in the United States are now pursuing legal action against SOS in Syria.”

You can watch the full BBC documentary below.

Jess Kelly is a BAFTA-nominated documentary filmmaker. She previously worked on the 2021 film “The Schools That Chain Boys,” which won major awards including the Royal Television Society Award, an Amnesty Award, the ARIJ Gold Award, and a Peabody nomination. Her 2019 BBC investigation, “Silicon Valley’s Online Slave Market,” exposed the illegal online trafficking of domestic workers. It was viewed over five million times and screened at the United Nations and in the British Parliament.

Jess Kelly is a BAFTA-nominated documentary filmmaker. She previously worked on the 2021 film “The Schools That Chain Boys,” which won major awards including the Royal Television Society Award, an Amnesty Award, the ARIJ Gold Award, and a Peabody nomination. Her 2019 BBC investigation, “Silicon Valley’s Online Slave Market,” exposed the illegal online trafficking of domestic workers. It was viewed over five million times and screened at the United Nations and in the British Parliament.

Haya Al Badarneh is a British-Jordanian journalist, producer, and filmmaker based in London, known for her work across the Middle East. Her 2024 documentary “Life and Death in Gaza” won a BAFTA and was nominated for four more. In 2023, “Gaza Diaries” and “Syria Captagon” received multiple global awards.

Haya Al Badarneh is a British-Jordanian journalist, producer, and filmmaker based in London, known for her work across the Middle East. Her 2024 documentary “Life and Death in Gaza” won a BAFTA and was nominated for four more. In 2023, “Gaza Diaries” and “Syria Captagon” received multiple global awards.

Bashar Deeb is an open source investigative journalist at Lighthouse Reports, where he focuses on human rights, conflict, and justice issues. He has been working in this field since 2018, and has contributed to multiple reports and collaborations with leading media outlets and organizations. His expertise includes open source intelligence, data analysis, geolocation, chronolocation, social media investigation, and tracking planes and ships.

Bashar Deeb is an open source investigative journalist at Lighthouse Reports, where he focuses on human rights, conflict, and justice issues. He has been working in this field since 2018, and has contributed to multiple reports and collaborations with leading media outlets and organizations. His expertise includes open source intelligence, data analysis, geolocation, chronolocation, social media investigation, and tracking planes and ships.