Mill Media founder and editor Joshi Herrmann speaking at the 2025 CIJ Summer Conference in London. Image: GIJN

Tips on Running a Successful Local Investigative Outlet

Read this article in

When it comes to sexy beats, local news ranks somewhere pitifully close to the bottom. Traditional local news stories about delayed trains and lost cats are important in their own right, sure, but they’re not likely to sweep up any Pulitzer Prizes. Few budding journalists have big dreams of writing quick-hit day stories, and according to the data, fewer people want to read them. Hundreds of local newspaper titles across the UK have closed in the past decade alone.

That’s what makes Mill Media — an outfit that now has six regional titles and 17 reporters across the UK; most of them young, some fresh out of university — so unique. Set up in 2020 as a Substack newsletter, founder Joshi Herrmann reflected on the first email that Mill Media fired into the void. “I wrote this post that tried to make the case for what I called a new newspaper,” he told CIJ Summer Conference 2025. “It was an audacious claim, given that there was one person, no office, no team, no freelancers.”

Having worked as a journalist for 12 years — and having enjoyed writing in-depth features and working on investigative stories — Herrmann decided that he would take the tired image of local news and remodel it, ditching the dull stories in favor of longform reporting. “I wanted to have the sense that what we were doing was in some way trying to get back what people used to get from local newspapers,” he explained. “So I tried to create a brand of local news that would feel different from what’s already out there.”

Mill Media founder Joshi Hermann (second from left) and members of his editorial team, including staff writer Jack Dulhanty (left), writer Dani Cole (center right), and senior editor Sophie Atkinson. Image: Dani Cole

That model has proved a great success for the organization, which now has 170,000 readers and 11,000 paid subscribers across Manchester, Sheffield, London, Birmingham, Liverpool, and Glasgow. Among their investigations are two stories that were recent contenders for the UK’s prestigious Paul Foot Award; one a four-part series exposing the poor conditions of charity housing in Liverpool, the other a seven-month investigation into a Manchester city official’s management of pandemic money.

While securing funding and cultivating an audience for hard-hitting investigations can present challenges, Mill Media’s watchdog reporting often brings a wave of new readers and subscribers. “We’ve found […] that our biggest growth moments are highly correlated with the moments when we’re publishing stuff that has taken weeks, months, or sometimes more than a year to put together,” Herrmann said. “Which is obviously a good sign. That type of journalism pays for us.”

With that in mind, Herrmann reflected on his top tips for running a successful local investigative outlet, and producing high-impact stories that generate a loyal readership.

Telling Stories

Herrmann started by putting the onus on something that “can sometimes fall by the wayside”: the art of storytelling. While documents and interview transcripts pile high on the desks of investigative journalists, it can be difficult to take a step back and think about how to tell the story in a way that creates an emotional connection with the reader. Herrmann emphasized just how important this is in Mill Media’s writing and editing process.

“If you think of a novelist or a Netflix producer […] they would first of all think about: What’s the story? What’s the story arc? How do I build tension? How do I resolve it? Who’s the character?” he said. “I don’t think investigative journalists can always make a story fit a perfect story arc, but I think storytelling is inherently more compelling, more interesting to people, than just a whole bunch of information.”

Herrmann compared this to telling a story verbally amongst friends: there’s a build-up, a teaser that there’s something exciting coming up, and then the final nugget of information when everybody is on the edge of their seats. “It would be very unusual for you to tell them all of the most important information at the start,” he says. “That would be the pub session over.”

Whether it’s novelists, documentarians, or stories shared over drinks that provide the source of inspiration, “we as journalists need to think more about what those techniques are,” he said, “because they’re incredibly compelling.”

Building Scenes

Another core element of the storytelling process is creating ‘scenes’ by picking up on the details, Herrmann said. “You’re not just trying to get the standard things that you learn about at journalism school — quotes, color, facts, corroboration,” he explained. “Scenes can capture something about a story or a person much better than any amount of exposition or explanation.”

When editing stories, Herrmann often finds himself asking reporters to continue building up a scene. “I’ll always say: ‘Can you go back to the source and find out where the [event] was? How many people were there? What was the atmosphere? What were people wearing? What struck people as unusual?’” he said. “You’re giving the reader a couple of paragraphs that get them inside the room.”

One such scene of note, Herrmann explained, can be found in a story published by the Manchester Mill in 2022: Simon Martin is Manchester’s best chef. Is he its worst boss?. In all, 16 sources spoke about allegations of abusive workplace behavior by Martin — a “brilliant chef” heading up a top Manchester restaurant, but a “tyrant at the same time” according to Herrmann. (Martin dismissed the 16 interviewees as “unreliable sources” and “disgruntled ex-employees” who were colluding to undermine his career).

The story captured a key moment in which Martin claimed to be on the phone with Danish Michelin-star chef René Redzepi during a staff night out. “A lot of [Martin’s] respect from his staff came from the fact that he’d worked with this amazing chef, [Redzepi],” Herrmann explained. “What an amazing thing to see your boss talking to the best chef in the world. And then, after a while, one of the staff members noticed that Martin’s phone was showing his home screen.”

“Not only was Martin not speaking to the greatest chef in the world, he wasn’t speaking to anyone,” he continued. “There’s no amount of explanation of Simon Martin that could convey the strangeness […] as well as that little image.”

Finding Your Characters

Elsewhere, it’s important to find the individuals that make your stories more interesting, Herrmann advised. “Great stories hinge on great characters. That’s not a traditional thing for investigative journalists to think about,” he said. “The most compelling stories we’ve done have had a very strong central character. What people really want from a story when they’re reading it is to learn how other human beings would deal with certain scenarios.”

Stuck on a piece involving a stock market investment fund and contracts in the social housing sector, Herrmann and his team had a breakthrough when they discovered that there was a central character who could draw people into an otherwise quite complex story. They focused on a property agent in Wolverhampton, who had an awakening at a Buddhist retreat and decided that he would solve homelessness.

Liverpool Post reporter Abi Whistance was shortlisted for the UK’s Paul Foot Award for her four-part investigation into a housing charity that left residents living in dire conditions. Image: Screenshot, YouTube

“What a backstory, what a guy,” Herrmann recalled. “Is this a guy who’s got good intentions, he’s acting in good faith, and then later something goes wrong and he turns out to be running something where people are living in such horrendous housing conditions that one woman died in one of his flats? […] People want to know that, because that’s a character story, that’s what character gives you.”

“If you want people to spend 20 minutes of their Saturday morning reading your investigation, you better try and latch them on early,” he continued. “You’ve got to grab people’s attention, and I think having a central character introduced as a human character very early on is an unbelievable way of keeping people inside the story.”

Take Readers Behind the Scenes

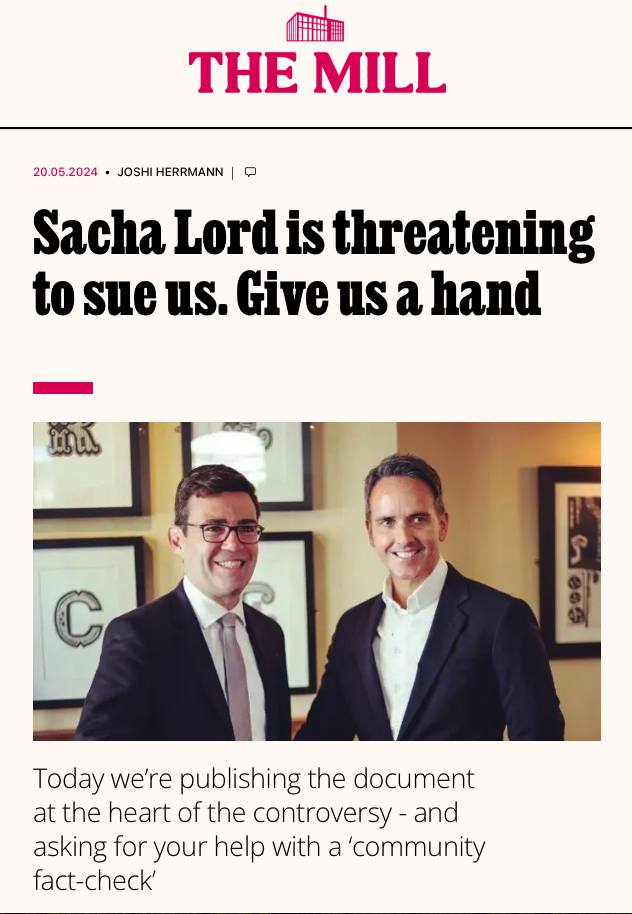

Following a two-part profile about Manchester city economic official Sacha Lord, The Mill received a tip off. The individual who contacted them claimed that he used to work for one of Lord’s companies, and had evidence that the businesses in question had illegitimately gained around £400,000 (US$540,000) from the government during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Mill published a story on this, and a day later, Lord responded through a lawyer claiming that the story was “factually wrong” and threatening to sue the site for defamation.

Manchester Mill’s appeal to readers after a defamation lawsuit threat from a city official. Image: Screenshot, Manchester Mill

The Mill decided that rather than following the standard process of consulting their lawyers and sending a reply, they would instead go public with the threat, sharing the FOI document from the investigation with their subscribers for a “fact-check” from the community. “It’s so valuable to get your readers more involved,” Herrmann said. “I felt that it was only by going public about his threats […] that we could actually win the battle. He’s got more money than us. He’s got the backing of [Manchester Mayor] Andy Burnham.”

“We basically said to our readers: ‘Here’s the document, help us out,’” Herrmann explained. Over the next few days, their subscribers sent in a raft of tips, and a whole team of journalists — including from their other regional titles — worked on the information coming in. “Three days of us publishing more and more damning details about how he had misled the Arts Council eventually resulted in the dam breaking,” Herrmann said, and Lord withdrew his legal threat.

“We were able to deploy our audience in a way that I think I’ve really learned from and I’d like to do again,” he concluded. “I feel like you’re changing the calculus. Suddenly you go public, and it’s very embarrassing for them. No one wants to look like they’re trying to bully an independent media company.”

Reflecting on the future of local investigative journalism, Herrmann emphasized the need for journalists to reframe their approach to local news. “Because what we basically need, for the future to be bright, we need every community to have a sort of renaissance in local journalism,” he said. “And I think we’re starting to see the grassroots of that happening. So that’s really very good to see.”

Emily O’Sullivan is a resource center researcher at GIJN. She has worked as an investigative researcher for BBC Panorama, and an assistant producer for BBC Newsnight. She has an M.A. in investigative journalism from City, University of London.

Emily O’Sullivan is a resource center researcher at GIJN. She has worked as an investigative researcher for BBC Panorama, and an assistant producer for BBC Newsnight. She has an M.A. in investigative journalism from City, University of London.