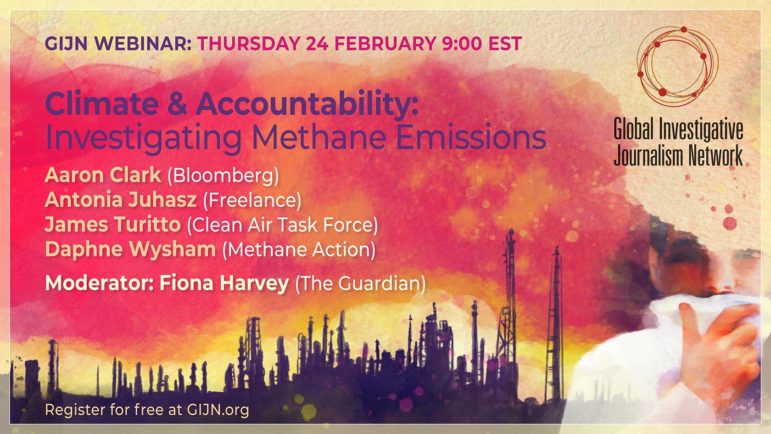

A map showing hazardous chemical incidents since January 2021. Image: Screenshot, Google Maps, Coalition to Prevent Chemical Disasters

Spill-Tracking Data Sources to Help Cover Hazmat Events and Environmental Disasters

The announcement earlier in February of a new, attractive and well-presented “Spill Tracker” website got plenty of media attention.

Data about chemical incidents (some of which are chemical disasters) is definitely something the public and environmental journalists should have. So you should certainly check out Spill Tracker. But you should also understand what it does and does not do — and what industry and government are doing to help or hinder you in knowing about dangerous spills. And you should also know about other related information sources.

Where the Data Comes From

First, it’s worth knowing that Spill Tracker is run by a group called Beyond Petrochemicals, essentially an environmental group, a coalition of partner groups, funded by Bloomberg Philanthropies.

The group’s purpose is to oppose petrochemical plants, especially proposed new ones, with an emphasis on environmental justice. Its director is Heather McTeer Toney, a noted activist who was also an Obama-era regional administrator for the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

So most of what’s on the Spill Tracker site is meant to persuade, rather than merely report — with the policy goal of stopping the approval, financing, and construction of new plants.

How to Use the Data Smartly

What the Spill Tracker site offers is not crunchable, structured “data” in the sense that data journalists think of it. Still, it may be a good source of news updates.

That’s because Spill Tracker is an updated series of links to news media accounts of incidents. They are not all spills; some may be things like flaring. They seem to be updated at least weekly. There may be several incidents per week.

Yes, there are definitional issues surrounding which chemicals and which incidents are really of concern. “Petrochemical” is a rather broad term, covering a multitude of sins. And it doesn’t cover all the substances that can harm humans. Chlorine gas, anhydrous ammonia, sulfuric acid, and hydrofluoric acid are dangerous to health, but not petrochemicals, exactly.

There is also a bias toward including catastrophically harmful incidents, rather than smaller releases that can add up to harmful chronic exposure over longer periods.

Other Data Sources on Petrochemical Incidents

If you’ve gotten this far, you are likely interested in data about petrochemical incidents. We’ve got some databases for that.

Chemical Incident Tracker: A group called the Coalition to Prevent Chemical Disasters puts out a very useful database of chemical incidents. The coalition is an alliance of scores of groups, mostly environmental, ranging from local to national in scope. They have been doing it since January 2021.

Nongeeks will love that this tracker presents its data in interactive map form; geeks will love that you can access the underlying data in table form. But don’t get too excited, because what’s underneath is mostly links to news media accounts. The whole thing is nicely searchable.

The data sources are not exclusively media articles — other sources are included (some are below). We applaud this tracker’s conscientious effort to lay out its “methodology.” That section leads to other sources. It’s also transparent about its policy agenda, which is to prevent chemical incidents and to strengthen the EPA’s Risk Management Program.

National Response Center: The federal government set up the National Response Center as a place where first reports of many kinds of spills, pollution, and disaster events are collected. It’s operated by the US Coast Guard, but it works with an array of other federal and state agencies.

Many of the reports it receives are required under a variety of environmental laws. For example, the US Clean Water Act requires companies to report oil spills. Similarly, the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act requires companies to report some kinds of toxic chemical spills.

The information reported to the Center was once easily available to environmental journalists in nearly real-time. But in 2015, the Obama administration made it much harder to access. Still, you can download some of the data in spreadsheet form online. There is a long time delay before it is posted. You can access what data is available here.

PHMSA Hazmat Incident Data: The Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration keeps data on pipeline and other transportation spills of hazmats. The best starting point for accessing this data is its search portal or its tool for Transportation Disadvantaged Communities Data. Its data is mostly limited to transportation incidents.

Toxics Release Inventory: This mother of all toxics databases tracks the handling of chemicals, including petrochemicals. It does not track catastrophic releases, but it does help you know where significant amounts of toxic chemicals are ending up — whether in a landfill or the atmosphere.

SkyTruth: A different approach to petrochemical spills, SkyTruth is a nonprofit that tracks oil spills and other events using geographic data from satellites.

ITOPF: The International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation is a group that tracks oil spills from tankers and other ships.

Resource Watch: This project of the nonprofit think tank World Resources Institute tracks oil and chemical spills worldwide.

NOAA: The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has an Office of Response and Restoration that responds to oil and chemical spills in coastal and marine settings. It keeps raw data on incidents it is involved in its Raw Incident Data files.

[Editor’s Note: For more on this topic, see a Feature on politicking over the chemical facility anti-terrorism standards, along with a TipSheet on tracking down the CFATS facilities. Also check out another TipSheet on using toxic chemicals data for reporting in your community, Toolboxes to help you use the CompTox chemicals dashboard, CAMEO software for covering chemical disasters and TSCA chemical data sets, and a Feature on how journalistic teamwork uncovered years of chemical regulatory failure in Texas. Plus, track related headlines with EJToday.]

This post was originally published by the nonprofit Society of Environmental Journalists and is reprinted here with permission. It has been lightly edited for clarity and style.

Joseph A. Davis is a freelance writer/editor in Washington, DC who has been writing about the environment since 1976. He writes SEJournal Online’s TipSheet, Reporter’s Toolbox, and Issue Backgrounder, and curates SEJ’s weekday news headlines service EJToday and @EJTodayNews. Davis also directs SEJ’s Freedom of Information Project and writes the WatchDog opinion column.

Joseph A. Davis is a freelance writer/editor in Washington, DC who has been writing about the environment since 1976. He writes SEJournal Online’s TipSheet, Reporter’s Toolbox, and Issue Backgrounder, and curates SEJ’s weekday news headlines service EJToday and @EJTodayNews. Davis also directs SEJ’s Freedom of Information Project and writes the WatchDog opinion column.