My Favorite Tools with AP’s Global Investigations Editor Ron Nixon

For GIJN’s My Favorite Tools series this week, we spoke with Ron Nixon, the newly appointed global investigations editor at The Associated Press. He joined the news wire as international investigations editor in early 2019, with responsibility over a team of six investigative reporters around the world. In that position he edited investigations into sex crimes within the Catholic Church in the Philippines, the cancellation of a vital shipment of cholera vaccines to war-torn Yemen, and the sale tactics of an opioid producer in China.

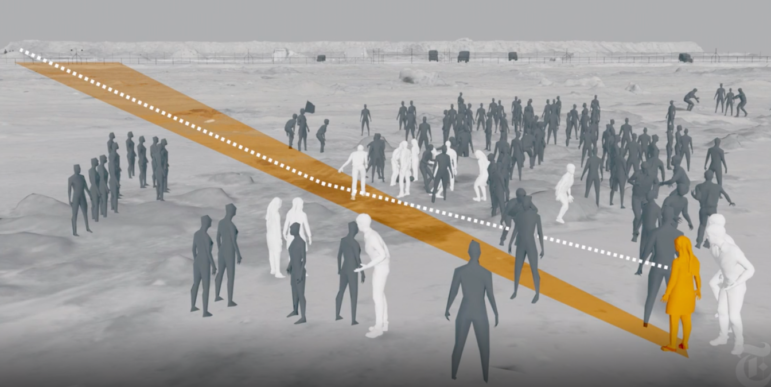

Since the COVID-19 crisis began, his team have turned their investigative lens onto the global coronavirus pandemic. Last month, for example, they published data analysis showing how millions of people left Wuhan before the Chinese city at the epicenter of the outbreak was placed under lockdown.

The global investigations editor at The Associated Press Ron Nixon. Photo: AP/Pablo Martinez Monsivais

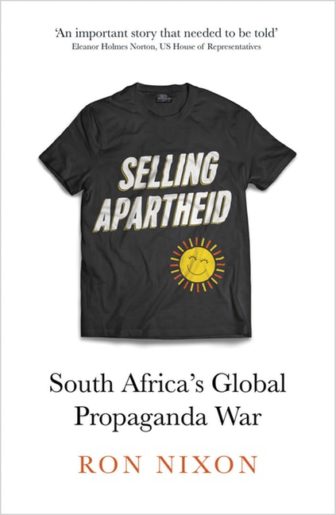

Before joining AP, Ron Nixon spent 13 years at The New York Times, where he first worked as a data reporter before covering homeland security, business, and a wealth of other subjects from various locations, including several African countries. His investigative work during this time included a piece on the US role in the Arab Spring, a domestic surveillance program at the US Postal Service, and a campaign to fight HIV and AIDS in Rwanda — a story that earned him a handwritten note from the Irish rock star Bono. While at The New York Times, he also wrote a book about South Africa’s global propaganda efforts during the apartheid era, “Selling Apartheid.”

Nixon first worked as a journalist for the statewide weekly newspaper South Carolina Black Media in the late 1980s. His first investigation was into police brutality against a black man – a story that nearly put him off investigative reporting for good, as he was taken aback by the threats of lawsuits that followed publication. His then editor convinced him to keep at it, he says.

He later worked as a reporter and editor at Southern Exposure Magazine in the southern US, where he investigated child labor, black church burnings, and discrimination in environmental policy. After that, he joined the Roanoke Times in Virginia, where he probed the Black Lung Program for coal miners and the state’s decision to withhold pollution data from the public. In the early 2000s, at the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Nixon helped pioneer data reporting, then known as “computer-assisted” journalism.

He has taught at Howard University’s School of Communications in Washington, DC, and the University of the Witwatersrand, in Johannesburg. Nixon also spent several years in the US Marine Corps in the late 1980s and early ‘90s, and fought in the Gulf War.

Here are some of his favorite tools:

Onionshare

“Onionshare is a secure tool for sending files through Tor, the anonymous web browser. Inspired by Edward Snowden’s leak of documents, it’s a point-to-point, computer-to-computer system. For it to work, both the sender and receiver have to be on their computers at the same time; if your computer screen goes dark, it cuts off the file share.

“I use it for sharing stuff with my reporters in China or in any other place where we are afraid that information might be intercepted. That includes video, documents, or anything else. For example, we shared documents back and forth using Onionshare for an investigation we did about the opioid epidemic in China.

“I use it for sharing stuff with my reporters in China or in any other place where we are afraid that information might be intercepted. That includes video, documents, or anything else. For example, we shared documents back and forth using Onionshare for an investigation we did about the opioid epidemic in China.

“I don’t trust any encrypted communication company 100%, whether Protonmail or any other. With Onionshare, there’s no third party involved. Once the person I’m communicating with has shared something with me, the link is cut off and nothing is stored online. Plus the actual communication is encrypted, so even if the communication were to be intercepted as it was taking place, you wouldn’t be able to understand what it contained.

“You definitely have to be careful when communicating sensitive information with China. I don’t take any chances there. We even encrypt ‘Hi, how are you?’ emails. So Onionshare helps us a great deal.”

Hushed

“Hushed is an application that allows you to make calls using private, disposable phone numbers, just like a burner phone. You can talk and text with it, and it’s encrypted as well.

“You can discard a phone number at any time and get a new one. So if I have a source that needs to call me, we’ll set up a way to call and then he or she would call that temporary number. Even if you find that number on their phone, you wouldn’t be able to trace it back to an AP journalist. Sometimes I use a phone number only once, sometimes a couple of times, but never for more than a week, otherwise it loses its function by becoming identifiable.

Hushed allows you to make calls using a disposable phone number from a variety of different countries.

“I sometimes use this with my reporters, depending on where they are. When I had a reporter in Ukraine last year, it’s what we used to talk, because we didn’t know if our phones were being monitored. Using a different phone number each time meant that anyone who might try to follow this person’s behavior would not know that they were talking to an editor in Washington. It would also have made it a lot harder to intercept any phone communication.

“Even with encrypted calls, you still see the point-to-point number, there’s no way to obscure that. What this does is generate a number that isn’t attached to anything, and then it just goes away. It’s fairly straightforward to use. You just download it from the app store and then pay as you go for the numbers you use. You can get as many numbers as you like.

“Using this kind of system with a source helps generate trust and confidence in that relationship. These extraordinary steps to protect their identity make people more likely to want to talk to you. Sometimes you educate sources on this kind of tool; sometimes they educate you.”

Air-Gapped Computer and Printer

“An air-gapped computer is one that is not connected to the internet in any way. We use it to open files when we’re not sure where they came from, because you don’t want to affect the entire system of the Associated Press — or any other news organization for that matter — when opening a leak.

“We have computers that are strictly not connected to the internet, and all they do is allow us to open stuff when we’re not sure of the source of the information. Let’s say we get a flash drive, we never put it into a computer that’s connected to our network, we put it into an air-gapped computer. If the flash drive infects the computer, you just wipe it clean and reinstall the system, but you haven’t infected your network. We analyze the information on that computer or do a first check there, using software to identify any malware, before moving it on to our regular computers if it’s safe.

“You just have to be careful. This is a standard thing that intelligence agencies and the military use. I was in the [US] Marine security forces, and an air-gapped computer is one of the tools they used for very sensitive material. At the AP, this way of doing things preceded my arrival. But we were using one or two really old computers, so I’ve tried to modernize our system, add more computers, and spread the knowledge throughout the organization that this is something we need to do.

“We also have an air-gapped printer, which is not connected to the internet either. When we get documents electronically we first print them out there, then scan them, before putting them back into electronic format. Printing them out ensures that we get rid of any metadata, anything that can identify the source of those documents. This is to prevent a repeat of what happened to Reality Winner, [the intelligence specialist] who had allegedly leaked documents to The Intercept. The FBI was able to trace the metadata on those documents back to a particular printer and eventually to her.”

Pandas

“Pandas is part of the Python programming language. It has become my go-to favorite for a lot of things because it allows you to do data analysis, web scraping, graphics, and statistical analysis all in one place. So I don’t have to analyze data in a database, then take that data and put it into a spreadsheet, then do statistical analysis, then take that and put it into some type of visual program. I can do everything in Pandas. If I need to scrape some data from the web, all I do is I write my script to scrape the data and then I just pull up the Pandas library in Python and analyze it there. I don’t need to go anywhere else.

“There is no data limit, as opposed to some software that starts to slow down after you get to a certain size. It’s built into a programming language, so everything is right there. I can run it on different computers, whether PC or Mac (unlike Microsoft Office on a Mac, which is different from Microsoft Office on a PC.)

“There is no data limit, as opposed to some software that starts to slow down after you get to a certain size. It’s built into a programming language, so everything is right there. I can run it on different computers, whether PC or Mac (unlike Microsoft Office on a Mac, which is different from Microsoft Office on a PC.)

“Pandas is just a function within the programming language itself. There are a bunch of libraries within Python allowing you to do all of these separate things there. Just like R, except that I find R more cryptic. But that’s just personal preference, having programmed in Python for many years.

“Some three years ago I did a story about Donald Trump wanting to cut a visa program. I used Python to download the data from the US Department of Labor and look at all the information, and then I analyzed it with Pandas. That data was publicly accessible online but it had to be cleaned because the format changes from year to year. So that’s why it was great to be able to do everything within Python. I could grab it, clean it, analyze it, spit out the useful data then write my story based off of that. It really accelerated that process.”

The Photo Investigator

“The Photo Investigator is a tool that we use to see the metadata that lies behind a photo. A year or so ago, we got photos of some documents from a source in Venezuela, and we were trying to authenticate them. He sent us pictures of the documents taken with his phone, rather than the actual documents, so we were able to look at the metadata to see where they were taken, whether they were taken at the time that he said they were, what phone they were taken on. Metadata reveals a great level of detail, including camera type, shutter speed, and geolocation. It was really helpful in authenticating the source’s claims.

“In the end we didn’t run the story. The documents were real but we only had one source for it. I’m never going to hang a story that sensitive on one source. But that’s the important thing to realize: the metadata doesn’t take you all the way, it just gets you one step closer to publishing the story. Even once I’ve seen the metadata, I still am not going to trust it unless I can match it with other things. There’s a whole bunch of other things editorially that you’ve got to do.

“What this tool can do is help you spot manipulation. If somebody is giving me a document that purports to be 14 years old, but it was actually created last week, then something is wrong. Likewise, if it was created in 2014 but I see it was modified yesterday, I’m going to be a little suspicious and ask myself: ‘What happened here?’ That sort of thing has happened to me, and Investigator helps me spot those cases.”

FOIA Requests, National Archives, and Lobbying Records

“We use Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests all the time. We don’t only use that tool defensively, we also use it offensively — to go after stuff before it’s in the news. If there’s a Boeing accident, we will put in a request to the Department of Transportation or the Federal Aviation Administration. But we also try to go after documents we just might have an interest in — policy stuff, budget documents — as a matter of course.

“We identify targets then file requests for those, because we know it’s going to take a hell of a long time to get what we need. The time it takes depends on the agency. With some government agencies, it can be quick. With others, it takes forever to get worthwhile documents. You build that into your planning, the fact that it’s going to take time. I once had a request that took three years to succeed, for a story on the companies that were doing business in both the US and Iran, in spite of sanctions. The data we used came from multiple sources, a lot of it obtained through FOIA requests. We had to request the licenses delivered by the Office of Foreign Assets Control allowing companies to work in Iran. We tried to get the documents, [but] they turned us down. So we then filed a lawsuit and eventually had our way.

“I’ll do a bunch of reporting before I actually start filing broad requests for things. That way, when it comes to filing a request, I will say, ‘I would like all the data that was compiled using a specific form,’ so there’s no ambiguity about what I’m looking for. You want to do as much reporting as you can to make sure that the authorities can’t wiggle their way out of it.

“I once tried to get documents from the US Congress, but Congress is not subject to FOIA. Still, it communicates with government agencies, and that communication is potentially accessible. So it’s important to think of the best strategies to access information and not just shoot off requests.

“Beyond the US, I’ve filed freedom of information requests in the UK, Germany, South Africa, and France. The Promotion of Access to Information Act in South Africa is fairly easy to use and in some ways it’s actually better than the US law, because it allows you to access information on private entities, so long as they have a public impact. If a company pollutes the water, for example, you can file requests for information about that company. You can’t do that here in the US.

“Beyond the US, I’ve filed freedom of information requests in the UK, Germany, South Africa, and France. The Promotion of Access to Information Act in South Africa is fairly easy to use and in some ways it’s actually better than the US law, because it allows you to access information on private entities, so long as they have a public impact. If a company pollutes the water, for example, you can file requests for information about that company. You can’t do that here in the US.

“I also used national archives and lobbying records a great deal for my book, “Selling Apartheid.” I didn’t necessarily have a specific idea in mind when I started my research. Regarding the British archives, I simply wanted to know what the British relationship with South Africa was during the apartheid years. So I looked at declassified memos from the Foreign Office to the Prime Minister relating to the government’s South African policy.

“In the US, the National Security Archive is an excellent source of declassified documents. This organization petitions the government to declassify documents and collects those documents that have already been declassified. I was able to get diplomatic cables between the US government and the UK about South Africa through the National Security Archive, for example.

“Lobbying records can also be a treasure trove of information and are often publicly available. Here in the US I’ve used the archives of the Office of Congress, which record general lobbying, and the archives of the Department of Justice, which record lobbying for foreign governments. These tools aren’t only of interest to historians, they can also be of great use to journalists doing investigative work.”

Olivier Holmey is a French-British journalist and translator living in London. He has written investigative reports on finance in the Middle East and Africa for Euromoney Magazine, and contributed obituaries to The Independent.

Olivier Holmey is a French-British journalist and translator living in London. He has written investigative reports on finance in the Middle East and Africa for Euromoney Magazine, and contributed obituaries to The Independent.