Letter from Islamabad: Inside the Deadly War Against Pakistan Media

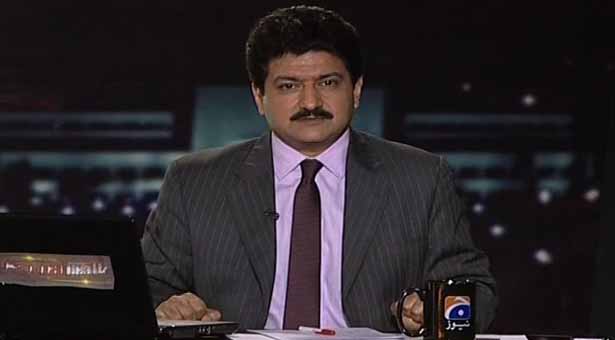

They wanted to kill him but he survived with six bullets in the body. He was not a case of mistaken identity. They knew who they were aiming at. Hamid Mir is arguably the most prominent TV anchor of Geo TV, the biggest network of Pakistan. He was not a stranger to threats. A bomb found planted beneath his car in November 2012 was diffused, to his good luck.

So when he was asked to host a special broadcast at Geo headquarters in Karachi over prospects of peace with the Pakistani Taliban, Mir began to feel restless. Already, he had curtailed movement within his home base, Islamabad, due to death threats. Traveling outside the city would be far more dangerous. While he reluctantly agreed to host the broadcast, Mir thought to trick his enemies so they couldn’t keep track of him. Therefore, instead of booking flight for Karachi, he purchased a ticket for Quetta, only to change it at the eleventh hour.

Nevertheless, the shooters knew when he flew to Karachi from Islamabad on April 19. They were also aware of the route he would use for reaching the studio there. They didn’t care about a security guard and a driver accompanying Mir from the Karachi airport to the Geo TV office. They opened fire at him when the car slowed down for a turn. As the driver geared up to escape the shooters, Mir was struggling to dodge the bullets being fired at him. He received six–in the ribs, thigh, stomach, and across his hand.

News of the near-assassination of Mir spread like wildfire. The staff of the TV network was emotionally charged. I work for the same media house, Jang Group, that owns Geo TV. Mir would frequent our office, situated in the same building where he worked. We would chat for a long time discussing issues ranging from current affairs to the threats against journalists.

He last visited us four days before this attack. Mir then shared concerns regarding threats to his life and the possible culprits. He had recorded a message for his family to release in case of any untoward situation. Geo TV’s top management was also briefed on the threatening messages sent to him time and again.

So when Hamid Mir was struggling for life, unconscious on a hospital bed, his brother Amir Mir, an investigative journalist, went on Geo TV to name the prime suspect in the attack–the chief of the ISI, Pakistan’s powerful intelligence agency. His statement was in line with the instructions of his injured brother. This turned out to be counterproductive.

No officials stepped forward to determine the veracity of Mir’s allegations and to look into the reasons for his suspicions towards the top spy chief. Instead, an organized campaign started against the victim journalist, his vocal colleagues, and Geo TV. The agency was not facing accusation for the first time. It has been accused in the past of harassing, torturing, and even killing a journalist. Saleem Shahzad, a journalist who was kidnapped in broad day light in May 2011, was later found dead; he had also expressed suspicions through an email.

While Mir sufffered from multiple injuries, Geo TV was next in the firing line. Running the accusatory statement of an injured employee turned out to be its crime. A complaint by the ISI led the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) to shut down the TV network, which was accused of having a history of “anti-state activities,” among other things.

Before the regulatory body would decide, the network was virtually shut down by the cable operators who succumbed to invisible pressure. A senior officer of PEMRA, which oversees the industry, held the operators to account for their illegal closure of Geo TV. He was picked up one night and tortured. The next day, he requested transfer to another position. The regulatory authority finally gave up. Forty-five days later after this near-closure, PEMRA slapped a 15-day suspension on Geo TV for running the allegations against the ISI spy chief. No right of hearing or even response was granted to the network.

The attack on Mir also brought to the surface cracks within the Pakistani media. A general perception about the nation’s lively news media is that they stand united against threats to press freedom. Such solidarity has turned out to be an illusion. Attacks from rival TV networks started accusing Geo TV of maligning the ISI. (As the accusatory statement pointing fingers at the ISI chief was run on TV, his picture was also flashed.) Even the demand for Geo TV’s closure initially came from the rival channels.

Holding Geo TV to task for broadcasting Mir’s allegations might seem odd when the Pakistani media has no qualms about routinely running serious allegations against the Prime Minister and President (the supreme commander of armed forces). The difference here was the allegations on Geo TV were against the spy chief of the most powerful agency in Pakistan.

Instead of discussing the possible attackers of Mir, the debate centered on the accusation and its coverage. Those who tried to highlight the case of a victim-journalist demanding a probe were targeted through talk show hosts close to the military establishment and harassed by different means.

My two colleagues and I received emails from someone identified as “Khaki power,” threatening us of dire consequences if we continued speaking out. Thugs were sent to the hometown of my colleague to resuscitate a police case against him that was quashed 10 years ago. Our female staffers were harassed into quitting the network. Male staffers were assaulted by “anonymous” attackers. The vans carrying newspapers were put on fire and the drivers tortured.

I was also under scrutiny for demanding legislation for the spy agencies. Unlike in many other countries, there is at present no law governing the functions of Pakistan intelligence agencies. They were founded through an executive order but no law was made to formalize their functions. I wrote several articles arguing for the legislation. It turned out to be my crime. I, too, came under fire.

Surveillance on me was intensified. Some anonymous officials went to the village where I was born and raised. They inquired about my reputation and took pictures of my house there. Then they visited the organizations I had collaborated with in different projects. The purpose was to spot some irregularities that could be used to defame me.

The Center for Investigative Reporting in Pakistan, which I founded in 2012, also came under scrutiny. I was dubbed a rent-a-journalist who works hand-in-glove with foreign interests. At my newspaper, our top management is being pressured to fire six journalists, my name included.

A hate campaign on social media was started to scare my colleagues and I into silence. Being an advocate of free speech, I hardly block anybody on Twitter, hoping they will learn to improve the quality of argument, but the abusive commentary and naked threats have become a permanent feature.

It is more than two months now since Mir was attacked. A lot has changed. Geo is struggling to stage a come-back. It has officially been restored but is still absent from TV screens in many parts of the country, as the cable operators are still keeping it off the air. While Geo tendered a public apology for “excessive and emotional coverage” of the attack on Mir, it also sent a defamation notice to the ISI demanding an apology or evidence to back up allegations that Geo engaged in anti-state activities. Neither has been done.

Censorship started creeping into the newsroom soon after this crisis started. It is now rapidly advancing. Geo TV, being the biggest channel, is the front line of defense against these attacks on media freedom. It is still fighting, but other networks have surrendered, angling instead for a share of the 60% of Pakistani viewers that Geo has controlled. Those who failed to compete in the marketplace are now conspiring against the network. They are gaining business but losing freedom. Meanwhile, journalism in Pakistan is suffering.

Umar Cheema is an investigative reporter with The News (Pakistan) and the founder of the Centre for Investigative Reporting in Pakistan. In June 2014 he was elected to the board of directors of the Global Investigative Journalism Network, where he serves as its Asia representative. Cheema writes on corruption, politics, and intelligence agencies, work that has resulted in his being abducted and abused. His refusal to stay silent about the attack has drawn wide attention to anti-press violence in Pakistan. Among his honors are the Knight International Journalism Award, the International Press Freedom Award, and the Missouri Medal Honor for Distinguished Services in Journalism. In 2008 he became the first Daniel Pearl Fellow to work at The New York Times. He holds a master’s degree in comparative politics from the London School of Economics.