A view of The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a memorial for the victims of US lynching and racist killings, located in Montgomery, Alabama. Image: Shutterstock

Investigating Cold Cases: How Two Journalists Dug Into Decades-Old Civil Rights Era Killings

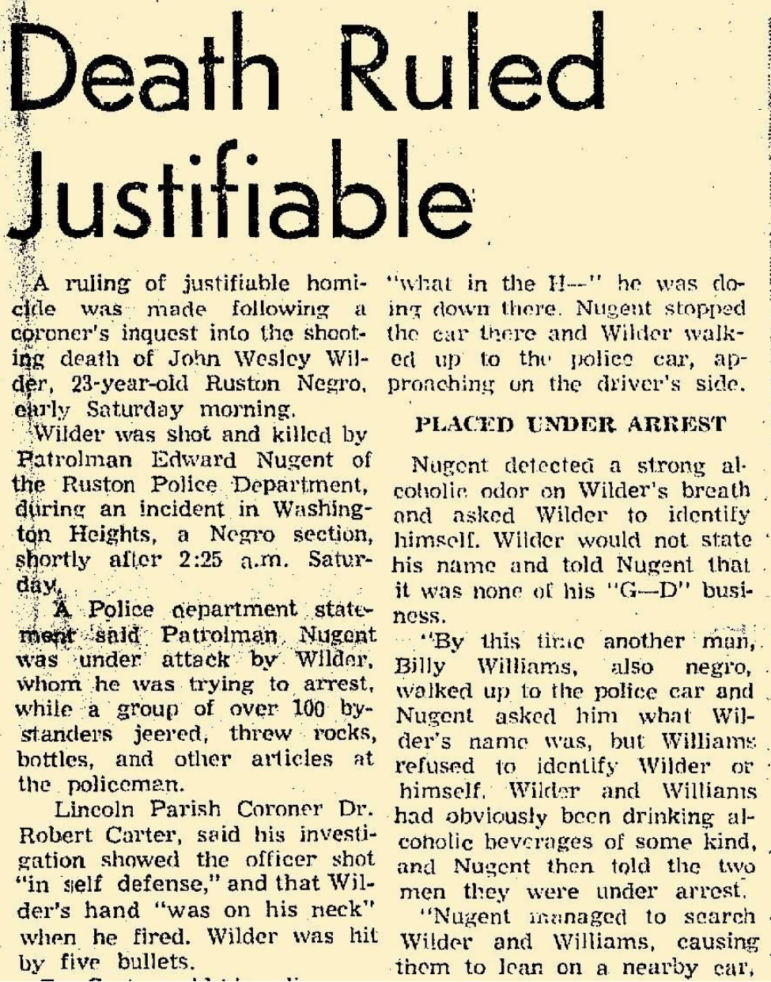

In July 1965, police officer Edward Nugent shot and killed John Wesley Wilder, a Black man outside a cafe in Ruston, Louisiana. The officer — who fired five times and claimed his actions were in self-defense — wasn’t charged, and authorities ultimately ruled the case a “justifiable homicide.” But decades later, journalist Ben Greenberg discovered evidence that suggested that the shooting was unprovoked — and after he began reporting, the FBI reopened the case.

Another cold case involved the 1968 killing of Carol Jenkins — a young Black woman who was killed in Martinsville, Indiana. No one was ever punished for the crime. But investigative reporter Sandra Chapman took up the story many years later, identifying a key witness with a new lead in the case.

In a recent webinar organized by the Fund for Investigative Journalism, both journalists shared how their investigations led to inroads in the cases, and how they used documents and eyewitness accounts to help their reporting.

Finding Their Way to the Story

Chapman, a local journalist at WISH-TV in Indianapolis, learned about Carol Jenkins’ killing when she was warned early in her career to stay away from Martinsville — a small town southwest of the city — because she is Black.

Ignoring that advice, she decided to talk to sources in the community, and while she sometimes faced pushback from community members who did not want to talk about the case, one day she received a call from a woman claiming to be the daughter of Jenkins’ killer.

“This case generated huge interest,” Chapman said. “We received many calls, some useful, others not. One voicemail caught my attention due to its details.”

The caller was Shirley McQueen, the estranged daughter of a veteran named Kenneth Clay Richmond, who would later be arrested in relation to the case. Chapman’s investigation resulted in a book published in 2012 and a 2023 documentary, both titled “The Girl in the Yellow Scarf.”

Greenberg, on the other hand, was an independent journalist and PhD student when he first got involved in the story. He began investigating his father’s involvement in the civil rights movement in the South, which led him to learn about unpunished racist murders and other violent incidents from the time.

In 2005, an infamous case of racist violence — which inspired the movie “Mississippi Burning” — was resurrected when former Ku Klux Klan member Edgar Ray Killen was indicted for his role in the 1964 murders of three civil rights workers in Neshoba County, Mississippi. The case piqued Greenberg’s interest, and his blog posts on the subject started getting attention from people in Mississippi and mainstream news outlets.

It was while researching these events that Greenberg came across information about the Wilder case. He visited the archives at the University of Southern Mississippi and found highway patrol and state police reports on the killing of Wilder and also uncovered sworn statements from eyewitnesses in an archive that had been ignored by the FBI and the police. The accounts from these eyewitnesses supported claims that the officer’s shooting of Wilder was unprovoked. His reporting culminated in a podcast episode for LWC Studios, A Death Ruled “Justifiable”: The Killing of John Wesley Wilder.

Verifying Eyewitness Accounts

To resurrect the cold cases, both reporters talked to a variety of sources, including families of the deceased, neighbors, and community members.

Sandra Chapman turned her investigation into the murder of Carol Jenkins into a book: “The Girl in the Yellow Scarf.” Image: Screenshot

“Everyone knew something about that murder,” Chapman said of the Jenkins case. “There was a lot of information, so we just kept pulling the thread.”

In 2002, an anonymous tip received by the Martinsville police prompted investigators to track down McQueen, who was seven years old when the murder happened. McQueen identified what Jenkins was wearing on the night of her murder, and said she had been in the back of the car and witnessed her father stabbing Jenkins as another unidentified man held the victim down. McQueen’s account was vivid and graphic. Months later, the police arrested the then-70-year-old Richmond on charges of first-degree murder. He pleaded not guilty and, before he could go on trial, died of cancer.

After McQueen connected with Chapman, she proceeded to access other documents that could confirm McQueen’s claims, like notes from her therapy sessions. This process also involved talking to more sources about the family, to figure out who Kenneth Clay Richmond was and to verify claims about his violent past and possible affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan.

“When you can go around and talk to a number of people, the story comes together and then, of course, we had to access records, FOIAs from the FBI, from various agencies. You put all of that together, and your story then begins to take shape,” Chapman explained.

Greenberg found that official police records did not match eyewitness accounts. He also managed to reach out to one person, Bill Smith, who had watched the shooting unfold.

“I told them what I had learned so far,” Greenberg recalled, “and he said: ‘That’s not how it went down.’” The witness — Smith — got into his car, drove to the scene, and started talking through what he saw as if he were reliving it.

Both reporters emphasized the importance of fact-checking eyewitness accounts to ensure accuracy, especially when these accounts do not corroborate police reports, but also stressed the value of finding witnesses from the scene of the crime.

Building Trust with Sources When Tackling Difficult Stories

For the reporters, it was important to build rapport with the community during the investigations.

“l’ll do a pre-interview on the phone and say I just want to know what you saw,” said Chapman about her calls to local residents in Martinsville. This was significant, because some people were afraid of speaking out and felt they could be isolated by their community. Building a connection with reliable sources was crucial because 1960s records weren’t well-kept. Chapman also noted the case of one investigator who took entire case files home. When this investigator died, no one could trace the files.

When Chapman got in touch with McQueen, she was careful not to re-traumatize her when asking for recollections from the night of the murder, so that the trust between them would not be broken.

“There’s so much more,” Chapman explained, “that probably would have made this story more salacious, but we didn’t include it because the point was not to harm or injure her, but to provide the necessary information to support the narrative of what had happened and what she could tell us about this killing.”

Greenberg also stressed that sources should be treated with care and sensitivity, especially if they have to recount traumatizing events that happened years ago. “I had to manage my own expectations,” he explained, about how much people are willing to share.

Investigating When Document Access Is Limited or Unavailable

Excerpt from the July 19, 1965 article on the killing of John Wesley Wilder by Ruston police officer Edward Nugent. Image: Screenshot, Ruston Daily Leader

In many active cold cases, law enforcement won’t share case files with the press or public because the investigation is ongoing. Both reporters said that they instead had to obtain access by filing FOIA requests, seeking resources from places like the US National Archives, and civil society groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

In the Jenkins case, the suspect, Richmond, died three months after he was arrested for the murder, but Chapman still needed to verify details about his life and background. So when Richmond’s daughter said that her father had been a veteran, Chapman decided to access his military records. She eventually got a trove of files that included information about his mental health, most of which aligned with McQueen’s account of her father’s behavior.

But Chapman and Greenberg also advised reaching out to the FBI or other federal agencies when trying to access information about cases where the suspect is deceased. Often, privacy laws no longer apply after a suspect or convicted criminal has died.

“If there were FBI documents generated when the case was first investigated decades ago, those documents tend to be available by a FOIA, even if the case has been reopened and it’s an active investigation,” Greenberg noted.

Tying Up Loose Ends

Both of these unsolved cases involved initial investigations that were perfunctory — witnesses who were ignored, motives and evidence that were either dismissed or not dealt with properly by the authorities, resulting in the cases being quickly closed. Through Greenberg and Chapman’s reporting, these cases came alive again in the public memory.

However, justice was never fully served in both cases. Edward Nugent was never arrested for Wilder’s death, even though the FBI reopened the case. And Richmond, who was battling bladder cancer when he was eventually arrested, was declared unfit to stand trial for Jenkins’ murder, and died soon after. The other suspect in her killing has never been identified.

Still, both Chapman and Greenberg assert that hard reporting and relentless digging into such cases are a way to ensure that the road to justice can be at least partially repaired, years or even decades after a crime.

Ngozi Monica Cole is a writer and journalist from Sierra Leone. She has reported for The New Humanitarian, The Continent, Reveal, and other outlets. Her work has been supported by the Pulitzer Center and FRIDA (The Young Feminist Fund).

Ngozi Monica Cole is a writer and journalist from Sierra Leone. She has reported for The New Humanitarian, The Continent, Reveal, and other outlets. Her work has been supported by the Pulitzer Center and FRIDA (The Young Feminist Fund).