A farmer applies pesticide to a cucumber crop near a residential area in Ogun, Nigeria. Image: Shutterstock

Investigating How Pesticides Banned in the EU Find Their Way to African Countries

Read this article in

In 2021, Jennifer Ugwa, a Nigerian freelance investigative journalist, was working on an investigation into the illegal dumping of end-of-life electronics in four African countries — Nigeria, Ghana, Cameroon, and Kenya — when she discovered another story.

While researching, Ugwa and her team found that there was an increase in the importing of pesticides in Nigeria that were banned in Europe. They decided to dig deeper — which resulted in an extensive investigation into the dumping and sale of pesticides in Nigeria that have been banned in the European Union, published in January 2025.

Some of these pesticides are banned in the EU because of links to cancer, child development issues, or pollution — but as Ugwa notes, “We found that chemicals that had already been banned from use in EU fields were still allowed in the Nigerian markets.”

The investigation was funded by an Earth Journalism reporting project through Journalismfund Europe, with a grant typically awarded to cross-border teams of journalists to conduct investigations into environmental affairs related to Europe.

The reporting spanned one year. Ugwa explained that it took time to scrape and confirm data, to get comment from the pesticide companies exporting to Nigeria, and to report on the ground at shipping ports, where the pesticides arrived, and markets in Niger State and Lagos, Nigeria’s capital.

The investigation, a multi-part series, examined the issue across three countries: Nigeria, Ghana, and Kenya. The article focusing on the issue in Ghana, by Gideon Sarpong, explores how EU-banned pesticides — with funding from European development banks — end up in rubber farms in Ghana. The Kenyan article is forthcoming.

The four journalists from three countries submitted a common proposal with the same theme for the grant. Ugwa said each article is produced independently by each journalist in the team.

This series reveals, as Sarpong put it, “environmental injustice” in the management of pesticide use and importation in Africa — enabled by legislative weaknesses — which can cause long-term health and environmental impacts. They point to the need for stronger regulations in African countries. Ugwa wanted to convey the human cost of the issue: “In terms of storytelling method, it’s an investigative piece that leverages a humanized narrative angle to highlight the issue.”

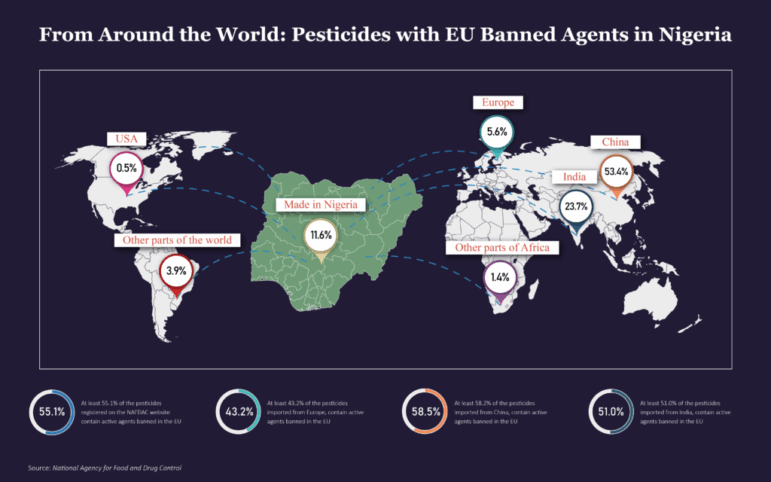

“To show the double standard, it was critical to show the actual harm resulting from this practice. I [used] graphics for visuals and other data tools, including mappings, to show inflow and data on the import levels.”

Exposing Impact

Ugwa said she wanted to see how many of these chemicals were being imported into the country, and what impact it has on the end users — farmers and their families.

Her investigation cited studies that show exposure to pollutants such as pesticides is associated with an increased frequency of cancers and solid tumors, particularly among agricultural workers. Her sources included industrial chemists, scientists, researchers, and health officials in Nigeria, and farmers who regularly come into contact with the toxic substances.

“I had another project at the time, so I thought I would just do a data story to show who is making more money and who is controlling the sales margins. Then, I realized the quantity was just one part [of the story],” she said.

After scraping the website of Nigeria’s National Food and Drug Administration Control (NAFDAC) — a government agency tasked with making sure that imported goods like pesticides come with the required standard for information on all imports, which included product number, name, and country of origin — Ugwa found that many of the products on store shelves used daily by farmers and traders had already been banned in the countries where they were made.

“I traced the origins of several pesticides found in Nigerian markets and farmlands back to European manufacturers. Many of these chemicals, like atrazine and paraquat, are outlawed in the EU because of their links to cancer, developmental issues in children, and environmental damage,” she notes. “But, they are still legally produced and exported — just not for European use.”

According to Ugwa, this shows that the companies are fully aware of the risks but continue to profit by sending them to places where regulations are weaker and oversight is minimal or nonexistent.

“While few of the EU-banned pesticides are imported from the EU – and the [European Commission’s] Chemicals Strategy aims to prevent this — companies are able to produce and export the products from third-party countries,” she noted in the investigation.

At the heart of the issue is that EU rules currently lack the teeth to prevent dumping or third-party export of harmful pesticides. A new EU corporate sustainability directive could hold companies to account for adverse human rights or environmental impacts, but it does not “automatically ban all export of pesticides that are banned in the EU,” Ben Vanpeperstraete, a legal advisor at the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights, told Ugwa. “What I uncovered was a system that allows manufacturers to keep their hands clean while quietly shipping these products to Nigeria because some of the products were imported from other African countries but produced by subsidiaries of EU manufacturers,” she adds.

Ugwa’s requests for comments from NAFDAC and a lobbying group representing six large agrochemical corporations went unanswered, and the European Commission “did not comment on its position on companies bypassing EU bans by producing their products in third-party countries to export,” Ugwa wrote in the investigation. A spokesperson for agritech company Syngenta claimed the company was no longer selling or distributing the products found at a chemical market in Lagos, and that they might be counterfeit; a spokesperson for Bayer wrote to Ugwa by email that it had stopped the sale of Topstar, which contains banned EU substances, in Nigeria in 2021.

When Ugwa spoke to farmers and local pesticide vendors, she found that most had no idea how dangerous these products could be, and they rarely wear protective gear.

“Most of them store dried food in pesticide canisters after use,” she points out. “I contacted NAFDAC months later into the report with some questions on importation monitoring and got no response. One year later, all the pesticide data was removed from the website.”

“Currently, we don’t know what is still available on the market, what has been delisted, or even what new cocktail of harm has been introduced based on data, because the agency decided just to take it all away and never gave an explanation despite numerous emails inquiring,” Ugwa explains.

Nigeria plans to phase out these products between 2026 and 2027. However, Ugwa says the current trend suggests a lobbying agenda.

“The article shows corruption, weak regulation, and profit taking priority over public health. At the heart of it all are the people — farmers, children, families — who unknowingly pay the price,” she says. In her investigation, Ugwa linked to a case in 2020 where more than 270 people, mostly farmers and locals from a community in the north-central region, died from pesticide poisoning. In addition, a 2022 study shows that 80% of the pesticides used most frequently by farmers were hazardous, with women farmers reporting symptoms such as respiratory and eye problems, dizziness, vomiting, and skin rashes.

“This wasn’t just an investigation into foreign chemicals; it was a window into a system that continues to fail the people it’s meant to protect.”

Challenges and Lessons

One of the biggest challenges in doing the investigation was obtaining data, Ugwa explained. She said that while she is not an expert in scraping and data, she worked with an independent, data-savvy expert who knew how to help provide meaningful resources for the story.

“When they [NAFDAC] deleted all the pesticide information on the website, that scared me, but thankfully, the original information was saved and backed up,” she explains.

She says getting responses from the parties identified in the investigation took months, but constant reminders and persistence were the most effective strategies.

“I was already working on another article on Nigeria’s biggest sugar mill, so I knew a bit about banned pesticides at the time, which also helped me understand what products were in demand,” she notes.

Ugwa said she was satisfied with her work on the investigation. “I felt relieved because sometimes, you start working on a story and you are thrown a curveball or, for whatever reason, get stuck, but that is one of the benefits of collaboration — although in this case it wasn’t a shared byline but group support, which helped to keep your head in the game.”

Patrick Egwu is a Nigerian-born freelance journalist who has reported from Chicago, Toronto, Johannesburg, Berlin, and Lagos for a number of publications including the Globe and Mail, Foreign Policy, NPR, Rest of World, Daily Maverick, World Politics Review, America Magazine, and elsewhere.

Patrick Egwu is a Nigerian-born freelance journalist who has reported from Chicago, Toronto, Johannesburg, Berlin, and Lagos for a number of publications including the Globe and Mail, Foreign Policy, NPR, Rest of World, Daily Maverick, World Politics Review, America Magazine, and elsewhere.