How They Did It: ProPublica’s Maternal Mortality Series

When ProPublica engagement reporter Adriana Gallardo and her colleagues published a questionnaire in February reaching out to women who had experienced life-threatening complications in childbirth, Gallardo only expected, at most, a few hundred responses. They received thousands — seeing 2,500 in the first week alone. The series based on this structured call-out to the crowd is now making waves.

Maternal mortality ratio (maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in women aged 15 to 49), by region, 1990, 2010 and 2015. Source: UNICEF

The genesis for the series began with the editorial team’s awareness of the puzzling and tragic statistics. As a 2016 study showed, the maternal mortality rate in the United States had increased from 18.8 (per 100,000 live births) in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 — the highest rate in the developed world. This increase of nearly 27 percent took place in the US while global rates fell by a third around that same time period.

After finding gaps in the data, Gallardo, along with ProPublica reporter Nina Martin and NPR special correspondent Renee Montagne, used social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter, as well as unconventional places like the crowdfunding site GoFundMe, to find the stories of affected women and their families.

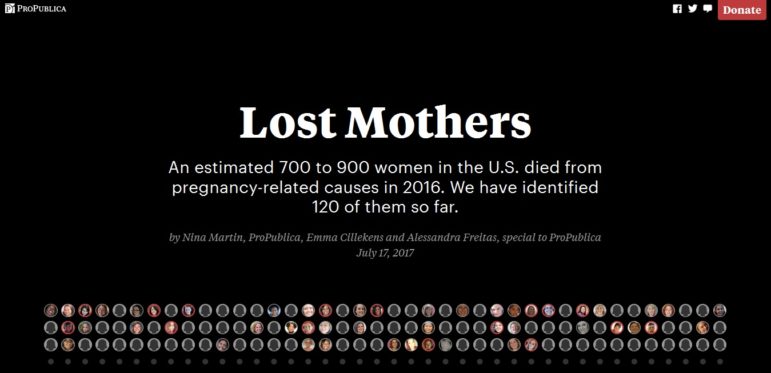

In ProPublica’s July installment of the series, they identify 120 women of the estimated 700 to 900 who died of pregnancy-related causes in 2016. Gallardo spoke with Storybench about what the reporting process was like and how the project has evolved over time.

Could you talk about what your job is and what it looks like day to day?

Adriana Gallardo: My title at ProPublica is engagement reporter, and it’s a title that’s only been around as long as my colleague Ariana Tobin and I have been in the role, which is about nine months for me and eight for Ariana. Last year, ProPublica decided that it was smarter to take someone off the social “hamster wheel” and dedicate them to actually reporting with the reporters in a different fashion that wasn’t going to be centered around Twitter and Facebook and social media. Our editor, Terry Parris, Jr., had done a really successful series with Charlie Ornstein on Agent Orange [relating to] veterans and their children and looking into the generational effects of Vietnam and Agent Orange, specifically. And that had worked out really well, and it really changed the way that ProPublica thought about social engagement in relation to investigative projects.

So the way that we’re working now is that we take each investigation on its own and think about what ways we can include community and nontraditional experts in the reporting process. We get traditionally at least six months to work on something, maybe longer, and so this leaves us with room to experiment and try to build communities in structured ways and unstructured ways. All of the women that shared a story with the maternal mortality project, I’m continuously in touch with them about their story, about what they contributed and often coming back to them with questions, more questions to guide our reporting. We don’t just ask and walk away; we’re very intentional about coming back — letting them know that we are real people behind these reporting projects.

Could you walk us through the maternal mortality story from your engagement strategy from the beginning. What did that look like?

Gallardo: It was the perfect scenario where we had huge information gaps where data was not available. State-tracking was minimal. We really couldn’t find any updates on who was dying, where they were dying and what were the causes of the maternal deaths. For that one, we thought a structured callout would be the best option and we spent months thinking about what would be the best set of questions to ask [of] women who nearly died and then also families of women who died.

We did pilot a form with new mothers and asked them what they thought about the questions that we had put together. Once we were confident that we had the best possible form, that’s what we launched the project with. And we did this in partnership with NPR. It was a way to plant the flag, but it was [also] a way to involve the specific community from the start and let the women at the center of the story be the ones to tell us.

The first story ran in May, so we had a few months where we were intently listening to this group of women that emerged and began to tell us, you know, what their life was like after this complication. Then, of course, we kept scouring the internet for cases of women who had died. That was a different challenge and that was where [we used] social verification and social research.

We were using GoFundMe, tons of searching on GoFundMe, which turned out to be a trove of information where families were actually uploading pictures and sharing details about someone who had died in their life, and they were asking for help. In the first week after launching the form, we heard from 2,500 women in the first week and that was a high volume for us and for NPR, as well. So then we knew immediately that there was a story here and that it struck a nerve and that we had asked the right questions, because people were very willing to participate.

So you make the callout and people start filling out the form and then where do you take that? Do you follow up with email? How did you convene that group?

Gallardo: We used a formbuilder called Screendoor that’s super secure and that has tons of flexibility for us to move through, label and analyze this information quickly. We put the form out with NPR on their Facebook page and our Facebook page and our Twitter accounts, and it just spread very quickly. Once the entries were coming, you know, I’m labeling them looking at location, causes, ages — all of the information that all of a sudden we were flooded with. We thought we’d get a couple hundred. We weren’t expecting thousands very quickly, and now we’re at about 3,300.

So you reach out to them individually. Do you convene them as a group in any way shape or form? Do you connect them together?

Gallardo: It’s something that we’ve thought about tons, and we haven’t connected them to each other yet. We’ve created other Facebook groups for investigations with ProPublica like Patient Harm with [reporter] Marshall Allen, and Agent Orange. We’ve been very careful because we don’t want to create a group that we can’t manage or a group that won’t have a moderator that can actually be a good leader for the specific group of women. We also really wanted to understand if the need is for the survivors, if the need is for the families left behind and is there overlap. And we’ve sent larger messages. We get very thoughtful replies from every time we send this type of email and I think after hearing from us over and over they definitely believe that it’s a continued effort. So it’s a very active group, and we take it very seriously.

What was the initial lightbulb spark for the whole project? Did you do some listening on social? Did someone come to the editorial meeting with an anecdote?

Gallardo: I think one of the editors of ProPublica had heard about the statistics that were alarming. So the US is moving in the opposite direction with maternal mortality. More women die every year. We knew the basis, the fundamentals. We were the worst among the developed nations.

But it was Nina Martin who has been reporting on women and health. She’s their gender and sexuality reporter in-house who really took it upon herself to begin looking for cases of women who had died recently. The challenges in her research really pointed to the lack of even public discourse.

Maternity is very much a romantic, mostly beautiful time for most women, but there are these cases that even the large mommy blogs tended to stay away from. We really couldn’t even read conversations about how complex and how traumatic some of these experiences were, because you know it wasn’t something that we saw as a leading discussion on any of the moms groups. We knew that it was a public health issue. Especially when you look at the racial disparities, this was something bigger than bad doctors or bad hospitals. This is a nationwide thing that we thought needed to be addressed.

Maternity is very much a romantic, mostly beautiful time for most women, but there are these cases that even the large mommy blogs tended to stay away from. We really couldn’t even read conversations about how complex and how traumatic some of these experiences were, because you know it wasn’t something that we saw as a leading discussion on any of the moms groups. We knew that it was a public health issue. Especially when you look at the racial disparities, this was something bigger than bad doctors or bad hospitals. This is a nationwide thing that we thought needed to be addressed.

The reporting is so rich in detail and terrifying all at once, particularly the lede of the first story and the story of Larry and Lauren.

Gallardo: It’s a devastating story, and you’ll hear about a second story soon that came off immediately on the heels of that story. Another woman died 10 miles away from where Lauren died (the woman in the first story), and she died of the same exact complications. Her husband reached out to us the day after the [first] story ran and said, “My wife just died of the same exact thing.”

So it’s time and time again we see how repetitive the issues are, and how apparently it’s happening everywhere — but it hadn’t been a national issue yet. So many people have reached out and said, “Help me talk about this. This is a very difficult thing to bring up to my pregnant friends. This is a difficult thing to bring up to women who I know almost died.” I actually asked the women in the group for advice on how to talk about this. That’s the kind of feedback loop that has been successful, and it’s true we definitely triggered a lot of things with the first article.

There’s a way in which journalism is moving more toward this connector role, with journalists bridging between communities. What is this type of work like, day in and day out?

Gallardo: I think what is different is that we’re not leaving throughout the story process. So we’re not thinking about this as a one-off — let’s [just] write a piece about the women who almost died. It’s more that we want to build a relationship with this group of people. We want to embed them in the process of reporting and then we want to stay in touch beyond the first story, second story, third story, because we know these are likely to be a series if we have that luxury. People need to know that somebody is watching areas of conflict. We’re reporters, but we’re also showing the vulnerabilities of how little we know about an issue. We’re creating a space where these folks feel in control of their narrative, but not just in a cheesy way of “sharing the mic.” You can tell when a story [has] been crowdsourced. There’s a human element in it. It’s not just data or editors or reporters talking about an issue.

This story first appeared on the Storybench website and is cross-posted here with permission.

John Wihbey is an assistant professor of journalism and new media at Northeastern University and an instructor in the Media Innovation Program. He is writing a book on the future of news.

Bridget Peery is a graduate student at Northeastern’s School of Journalism and a freelance photographer.