Yousur Al-Hlou, senior video journalist at The New York Times, discusses how on-the-ground reporting works in concert with visual forensics. Image: Edvin Lundqvist for GIJN

How Old-School Field Reporting Powers High-Tech Visual Investigations

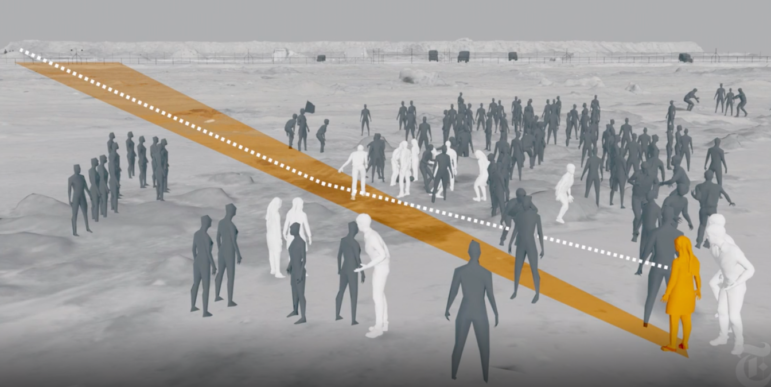

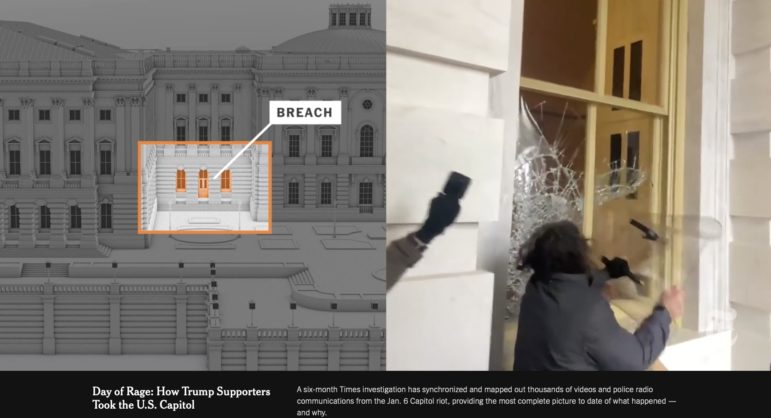

The breakthrough field of visual forensic investigations conjures a mental image of technical experts matching event timelines between video clips on their computer screens, far from the incident they’re probing.

But it turns out that the key to this technique — in which culprits are identified and events are reconstructed, moment by moment — is traditional, on-the-ground reporting, not the sophisticated forensic tools used later in the process.

That’s because field reporters without special tech skills are the team members who persuade witnesses to share their sensitive video clips; who help shopkeepers in war zones activate their CCTV units during electricity blackouts; who provide the emotional element to otherwise “cold” forensic stories by bearing witness to the harm.

In a session at the 13th Global Investigative Journalism Conference (#GIJC23) in Gothenburg, Sweden, Yousur Al-Hlou, senior video journalist at The New York Times’ pioneering visual investigations unit, revealed how she and her colleague, Masha Froliak, spent months in Ukraine in 2022 to gather the raw evidence for the Times’ award-winning Bucha war crimes investigation.

Al-Hlou credited her New York-based tech-savvy teammates for their epic work to verify and present the final evidence showing that a Russian paratroop regiment — and a commander they were able to name — were responsible for the massacre of civilians on Bucha’s Yablunska street last April. But she said it was important that the journalism community understood the role that field reporters play in these high-tech projects, for several reasons. One is that many newsrooms are currently in the process of designing their own visual investigations units from scratch; another is that dogged reporters without special computer science skills should feel confident in applying to join one of these teams.

Washington Post visual investigations reporter Meg Kelly, Yousur Al-Hlou, and Malachy Browne (left to right) speak at the Visual Investigations panel at GIJC23. Image: Edvin Lundqvist for GIJN

“A lot of people might assume that the work at The New York Times visual investigations team requires fancy tools, specific technologies, and office-based work, but that’s not always the case,” she explained. “I don’t know how to use any of the fancy tools. But, oftentimes, you’re only able to gather credible evidence if you meet with sources face to face, and if you can convince them that you’re the right person to work with their sensitive materials.”

Also speaking at the conference session on “Visual Investigations: Reporting Techniques” was Al-Hlou’s colleague Malachy Browne, senior story producer for the Times’ visual investigations team. He described an ever-expanding list of investigative subjects that visual forensic journalism is tackling. Recent Times projects include a missile attack against a civilian airliner in Iran, the classified military document leaks by a young US airman, and the police killing of Breonna Taylor. He said his team’s forensic toolbox now includes tools such as 3-D modeling software, facial matching, AI-driven object recognition, satellite imagery — and even satellite radar for cloudy days. However — echoing Al-Hlou — Browne said even the technical side of the team starts with sources and traditional reporting.

For the Bucha story, the key breakthrough involved the visual investigations team tracing social calls made by Russian soldiers — using phones the soldiers had stolen from murdered Ukrainian civilians. But the technique relied on the team’s field reporters collecting the phone numbers of those victims during interviews with their families in Bucha.

“The team used open source investigations methodology on the project, but the story was actually based on material we collected from on-the-ground field reporting, using the human touch,” Al-Hlou explained. “One day, we decided to talk to a man who was picking cherries. As we did every day here, we asked: ‘Were you here during the occupation?’ ‘Do you have a cell phone?’ ‘Did it have power?’ ‘Were you recording any footage in March?’ He took his phone out and said: ‘I don’t remember what I recorded, and I deleted some stuff. Why don’t you take a look?’ Well, he had the most important piece of evidence in there.”

She said the man’s phone included time-stamped photos and videos showing a clear chronology of the day Russian soldiers killed civilians in his neighborhood.

“We quickly went to the month of March in his phone, and we found a couple of videos that showed his perspective of the attack, where he was holding his camera at great risk to his personal safety because Russian soldiers threatened to kill residents who captured footage of them,” she said.

Al-Hlou said the months she and her colleague, Froliak, spent on a single street in liberated Bucha — producing half a dozen stories — transformed residents’ perception of them from “pestering” outsiders to trusted members of the community.

“The whole project was eight months, and, obviously, it’s not every story where you have the privilege of that kind of time, and it’s expensive. You have to book flights, book hotels, have a security advisor, take multiple trips. Every document you collect and every interview you do in a foreign language needs to be translated.”