How Forensic Architecture Supports Journalists with Complex Investigative Techniques

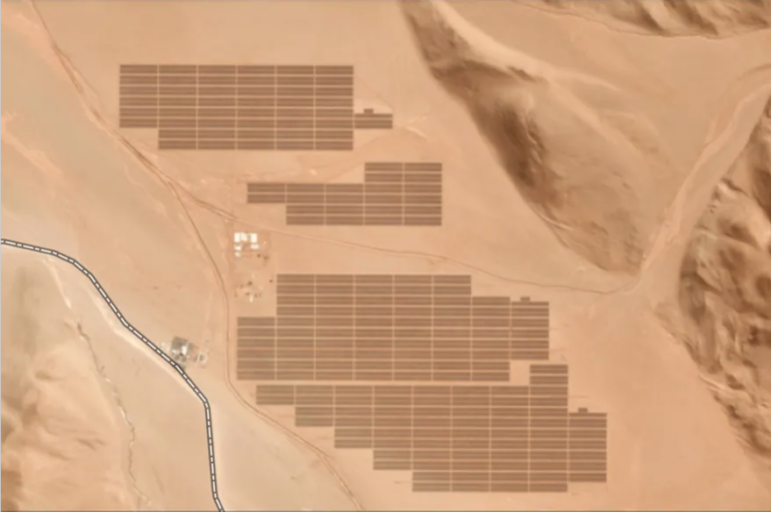

Forensic Architecture’s team members “hack into the source code of architecture” to investigate their stories. Image: Courtesy Forensic Architecture

In March, as the devastating potential of the COVID-19 pandemic came into full view, Israel’s prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced drastic measures ostensibly aimed at curtailing the spread of the virus.

To reduce social contact, he shut down the courts; to track the movements of those who had been infected, he authorized the use of cellphone data. But while both acts might indeed have carried health benefits, the former delayed the start of Netanyahu’s own trial on corruption and bribery charges by 10 weeks, while the latter legitimized a pre-existing but secret program of surveillance by the country’s Internal Security Agency.

“The pandemic in Israel is a kind of smoke screen behind which the buttressing of the right-wing government is taking place,” Eyal Weizman, the Israeli-British founder and director of human rights research group Forensic Architecture, tells GIJN. Elsewhere, too, governments have claimed to “follow the science” as they enact policies that curtail civil liberties in the interest of fighting the pandemic, often without releasing the full scientific basis for those decisions.

While withholding judgment on the various measures implemented, Weizman rages against that logic. “The moment you turn a certain scientific finding, or scientific data, into a guideline, into a decision, this is where the filtering of ideology comes in,” he says. “There is no pure science.”

Forensic Architecture is premised on the idea that civil society should be confident in employing science as a means to shape public debate and policy. By using forensic methods of investigation, many of which have historically been the preserve of law enforcement, Forensic Architecture is able to reclaim some of the legitimacy typically monopolized by state actors. This approach has allowed the organization to convincingly cast doubt on official accounts of airstrikes in Syria, land ownership in Israel, environmental destruction in Argentina, and disappearances in Mexico.

Today, it also makes it particularly well equipped to interrogate the ways in which authorities handle everything from health emergencies to police brutality. “The idea of civil society having access to scientific techniques in order to hold government to account is more important than ever,” Weizman says.

Activist Architecture

Few in the field of architecture would have seen that as their mission some 20 years ago. But Weizman, who was born in Haifa, Israel, and educated at the Architectural Association in London, came to realize the political potential of architecture early on, while studying how town planning in the Israeli-occupied territories might violate human rights. In 2002, the Israeli Association of United Architects cancelled an exhibition on settlements to which he had contributed, further reinforcing his view that architects had an important, if sometimes contentious, role to play in broader society.

Rather than working as an architect, he decided that he would “hack into the source code of architecture,” as he puts it, using its tools to shed light on political and social issues.

Weizman founded Forensic Architecture in 2010 to put this idea into practice. Its first project, commissioned by the human rights lawyer Michael Sfard, used 3D imagery to demonstrate the negative impact the proposed construction of an Israeli wall would have on the Palestinian village of Battir. The evidence bolstered an ultimately successful court case brought by Sfard.

Its latest project, published in June, revisited the contentious killing by British police of Mark Duggan, which ignited protests and riots in several English cities in 2011. The investigation, commissioned by lawyers for the Duggan family, brought into question the official account of the incident, and fed the ongoing debate around police violence in the United Kingdom.

Forensic Architecture has published close to 60 investigations in all, covering events in 18 countries. While some, such as the Battir project, have yielded tangible results, Weizman says that starting a debate and putting pressure on authorities is, in itself, a victory.

To give each project the greatest chance of reaching as broad an audience as possible, Forensic Architecture not only publishes its findings on its website, but also partners with media organizations, among them Bellingcat and BBC Africa, as well as with museums. One exhibition it held in 2017 in Kassel, Germany, showcased findings that undermined the testimony of a German intelligence officer for the state of Hessen, who had claimed not to have witnessed a killing by neo-Nazis in 2006, though he was at the scene of the crime. The exhibit brought much renewed attention to the case, and forced a response from German authorities.

But more than just guiding public discourse, Forensic Architecture aims to develop new tools that can be replicated by others. “We are not an investigative agency; we are like a lab for the development of new evidentiary techniques,” Weizman says. “The minute that our techniques and technology become more mainstream, we need to move on.”

Projects are chosen on their individual merit, but also on the basis of how much innovation they might require. “With every new project that we take on, we’re trying to figure out if there is some technique we could develop further,” says Christina Varvia, the agency’s deputy director.

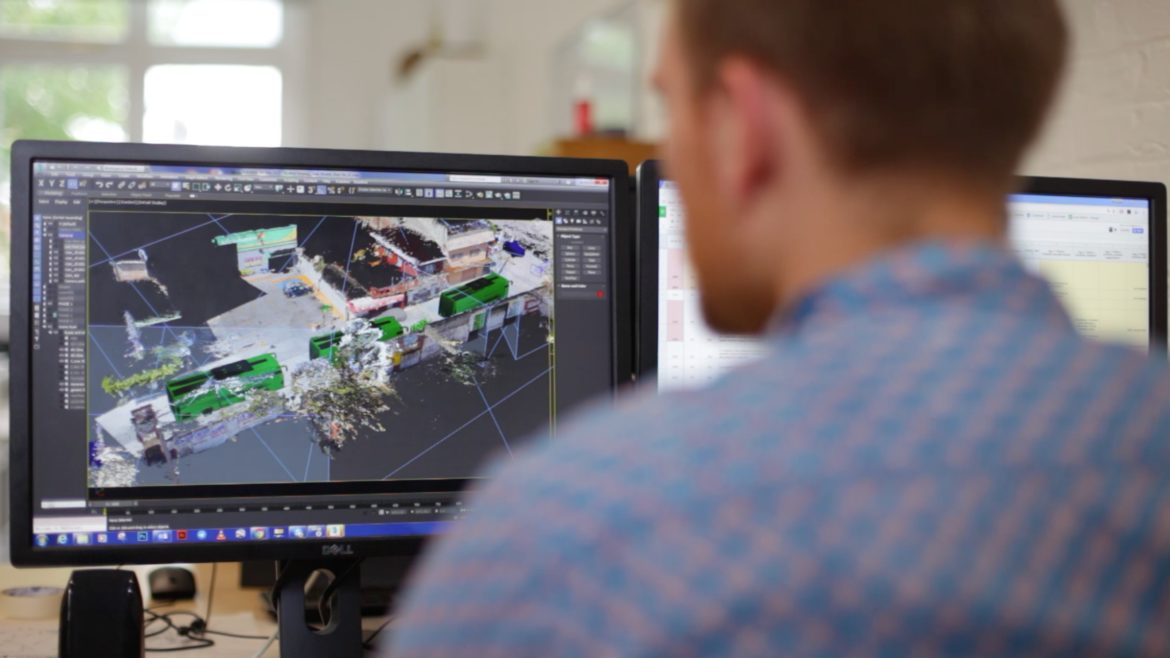

Forensic Architecture’s original project required the use of satellite imagery and on-the-ground measurements to develop 3D modelling. Since then, it has gone beyond the techniques most commonly found in architectural practice, by using data mining, software development, machine learning, and audio analysis, among other tools, to investigate events.

Some methods have been particularly innovative. To investigate a house in the east African nation of Burundi suspected of being used as a secret detention center, Forensic Architecture reconstructed a digital model of the building’s interior. The agency then interviewed witnesses, using the model to help them remember what they had experienced.

A journalist working on one of Forensic Architecture’s spatial investigations. Image: Courtesy Forensic Architecture

Conversely, in a separate project conducted in association with Amnesty International, Forensic Architecture was able to approximately reconstruct the inside of Saydnaya Prison, near the Syrian capital Damascus, by interviewing former detainees. Their account formed the basis of the prison’s virtual modelling, which in turn brought back further memories of torture and ill treatment.

“These models become another form of testimony, because they are made by the witnesses,” Varvia says, adding that one needs to be particularly sensitive to the trauma one might uncover in these sessions.

Collaborating in the Field

The Forensic Architecture team at their south London headquarters. Image: Courtesy Forensic Architecture

Investigative journalists are certainly paying close attention to Forensic Architecture’s work, and many have praised its innovative contributions to the field.

Ron Nixon, global investigations editor at Associated Press, tells GIJN: “The more we can incorporate these kinds of skills into how we do journalism, the better.” Nixon, who has not collaborated with Weizman’s agency but calls the Burundi investigation “freaking brilliant,” adds: “If we don’t do it ourselves, we can partner with groups like FA.”

Malachy Browne, senior producer of visual investigations at The New York Times, is equally enthusiastic. Browne, who has partnered with the research group on two projects thus far, says its work has influenced his team. “Forensic Architecture are forerunners and leaders in using advanced techniques to collect evidence, analyze it, and reconstruct events in time and space,” he tells GIJN.

The agency’s team is 20-strong, and includes architects, software developers, filmmakers, investigative journalists, artists, and lawyers. It is based at Goldsmiths, University of London, where Weizman is a professor of spatial and visual cultures, but it operates independently.

It has various sources of funding, but its largest donor is the European Research Council, which is providing a €2m ($2.2 million) grant over five years. A number of human rights organizations provide further core support through smaller grants, and the agency receives project-specific funding for commissioned investigations (some of which take an investigator a few months, while others take a whole team of people a number of years).

Lastly, some revenues are also drawn from the exhibition and acquisition of work to artistic and cultural institutions.

Unsurprisingly, the nature of Forensic Architecture’s work has also drawn rebukes from high places, from Germany’s Christian Democratic Union party to Syria’s president Bashar Assad. Most recently, in February this year, the United States revoked Weizman’s visa, after a Department of Homeland Security algorithm identified an unspecified security threat associated with him. The visa withdrawal was widely interpreted as push-back against the adversarial nature of Forensic Architecture’s work. Other members of the team are also barred from visiting certain countries, Weizman says.

Beyond such actions, Weizman sees reason to fear that increasingly authoritarian governments might seek to use the pandemic to tighten their hold on power. “We are obviously nervous about the kind of use and persistence of the new normal that would use the emergency in order to shift and erode principles of civil liberty,” he says.

All the more reason, he argues, to keep conceiving new ways to interrogate, and challenge, official narratives.

Olivier Holmey is a French-British journalist and translator living in London. His work has appeared in The Times, The Independent, Private Eye, NiemanLab, The Africa Report, and Jeune Afrique, among other publications.

Olivier Holmey is a French-British journalist and translator living in London. His work has appeared in The Times, The Independent, Private Eye, NiemanLab, The Africa Report, and Jeune Afrique, among other publications.