Residents of Solino, a suburb of Port-au-Prince, were forced to flee when gang violence erupted. When they returned, they found their houses had been destroyed and looted. Image: Courtesy of Jean Feguens Regala / AyiboPost

Seeking the Truth, in the Midst of a Country in Crisis: Haiti’s AyiboPost

Read this article in

Most mornings, when 26-year-old journalist Wethzer Piercin walks to work in Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s capital, he says he “sees corpses in the street.” Being a journalist in Haiti, he explained, means not only witnessing daily violence but also being one of its potential targets. “It is very difficult to live this,” Piercin says. “Anything can happen at any moment… you can get hit by stray bullets, you can be kidnapped,” he adds. But, “no matter what, you do your work.”

Piercin works at AyiboPost, one of Haiti’s most respected media platforms and one of its last remaining investigative journalism newsrooms. There, he says, they believe in a common mission: “Seeking the truth.”

Since last fall, armed gangs have torched TV and radio stations, kidnapped at least one journalist, nearly lynched others, and killed or injured several more. In 2024, the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) ranked Haiti first in its Global Impunity Index — above Israel — for failing to hold killers of journalists accountable. “A weak-to-nonexistent judiciary, gang violence, poverty, and political instability have contributed to the failure to hold killers to account,” the report stated.

The crisis escalated in 2021 after the assassination of then-President Jovenel Moïse, when gangs seized large swaths of the country. At the time, CPJ warned that Haiti’s press faced an “existential crisis,” forcing many outlets to shut down. Yet AyiboPost has endured — remaining unbowed and committed to investigative journalism despite grave threats.

“The streets are deadly, and international interest in Haiti’s stories is far lower than during past crises,” attests editor-in-chief Widlore Mérancourt. “As both an editor and a reporter, my concerns go far beyond the craft itself — I constantly have to think about the safety of my team, relocate staff who are in danger, and run a newsroom that adapts to fast-changing conditions.”

Founded in 2014 by Jetry Dumont and Naïké Michel, AyiboPost began as a participatory blog for Haitians worldwide to share analysis. It has since grown into one of the country’s most trusted newsrooms, with some 20 staff members and tens of thousands of monthly readers. The team publishes primarily in French and Haitian Créole and translates content into English and some in Spanish. AyiboPost finances its editorial operations through sister projects, including audiovisual and sports content, and partnerships with non-governmental organizations that allow it to maintain its independence. Its reporting has inspired youth protests for democracy, exposed corruption, and revealed overlooked details about Moïse’s assassination — including failures in his security systems. Threats resulting from reporting on Moïse eventually forced the team to vacate its offices.

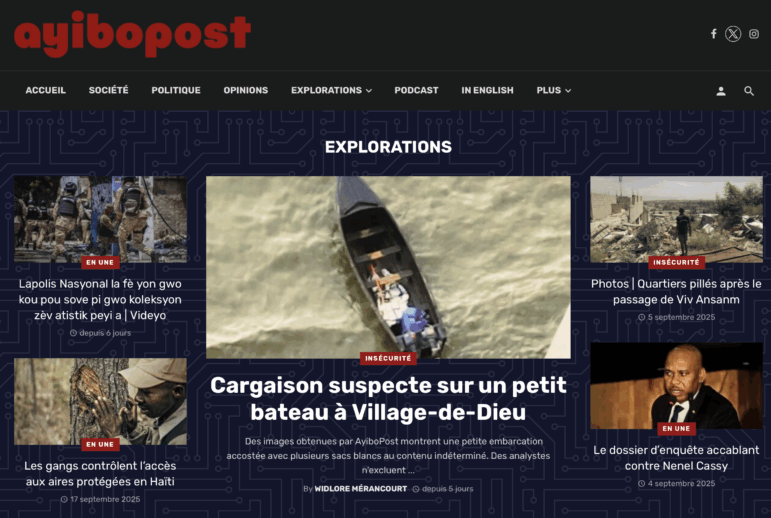

AyiboPost publishes its investigations in multiple languages, as seen in this selection of recent “Explorations” stories. Image: Screenshot, AyiboPost

Piercin joined AyiboPost in 2023. As a teenager, he launched a blog about art, music, and culture with friends, which sparked his love for storytelling. “I love giving meaning to things around me, and I love giving people voices,” he explains. “As a young Haitian, I have a duty to help this country, to involve myself in the memory of this nation that I love… that’s the reason I came to journalism.”

In 2024, Piercin co-authored one of his most notable stories with Mérancourt. It was an investigation that examined the gang coalition Viv Ansanm, showing its terrifying displacement of poor residents alongside its conspicuous luxury property investments in Port-au-Prince’s Village de Dieu. “The reality of Haiti is complex,” Piercin notes. “We are trying to tell the truth of Haiti — not only for Haitians, but also for people abroad — so they can understand the complexity of the situation.”

In 2025, Piercin collaborated with Forbidden Stories, a French nonprofit that continues the work of slain or threatened journalists. The joint investigation followed the reporting of Gary Tesse, a Haitian journalist murdered in 2022, and probed the alleged land-seizing schemes of a former prosecutor accused of orchestrating Tesse’s killing.

“AyiboPost is one of the few investigative outlets still left in Haiti,” says Eloïse Layan, a Forbidden Stories reporter who worked with Piercin. “AyiboPost continues to investigate, denounce the corruption of the political and economic elite, analyze the shortcomings of the international community’s actions, denounce gang abuse, and give a voice to victims,” she says. “It is quite remarkable to continue investigating in a country where corruption is rampant and a former president has been assassinated.”

David C. Adams, CPJ’s Caribbean correspondent who covers Haiti for The New York Times, noted that around 10 journalists have been killed in Haiti in recent years. Yet, he said, AyiboPost’s team continues doing “admirable work with very limited resources.”

“Their investigative pieces are the kind of journalism no one else is doing or is able to do in Haiti,” he said. “They want to give Haitians the truth, and it conforms to the highest standards of international journalism.”

Still, the risks are real. In 2024, AyiboPost’s Mérancourt revealed that Reuters journalists had offered gifts — including balaclavas, alcohol, and cigarettes — to gang leader Jimmy “Barbecue” Chérizier. The exposé raised ethical alarms about the practice and ensuing risk to Haitian reporters. (A spokesperson for Reuters said at the time: “This was an error in judgment. We are investigating and will take appropriate next steps.”) Mérancourt was later forced into hiding after Chérizier threatened to “come for him” over the story.

The team of the AyiboPost discuss stories in work at their current newsroom in the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince. Image: Courtesy of AyiboPost

For 27-year-old reporter Lucnise Duquereste, AyiboPost’s only female journalist, the dangers are compounded by gender challenges. “We expose ourselves to harassment and various violations,” she explains. “I’m very careful about what I post on social media, what I share, my location… it’s a maximum of prudence.” Duquereste reduces travel and doesn’t take public transport unless strictly necessary, preferring instead to speak to some sources by phone.

Duquereste’s reporting has spanned from the eel trade between Haiti and China to mystical practices that exploit women to local government mismanagement. “Each story, each reportage, each source remains engraved somewhere in my memory, their story, their past, their experiences,” she says. “It’s a collection of memories.” And, in part, why she says she believes journalism “chose me.”

To disconnect from the daily weight of her work, Duquereste turns to watching movies, engaging with friends, and enjoying social media. “We agree that the situation is difficult. There’s constant fear in your life. But as a professional, it’s a mission for me — to participate in Haiti’s change,” she says.

As an editor, Mérancourt is constantly having to assess the risks to his staff, but the confluence of recent events has created a “lethal environment for reporters.”

“Journalism has never been more necessary,” he emphasizes. “Yet too often the price we pay, both psychologically and physically, feels unbearably high.”

Annie Hylton is an award-winning investigative journalist and magazine writer from Canada. She writes about gender, migration, human rights, and conflict, and has reported from the Middle East, Central America, and Africa. Her work has been published by The New Yorker, Harper’s, The New Republic, and the London Review of Books. She teaches investigative journalism at Sciences Po Paris.

Annie Hylton is an award-winning investigative journalist and magazine writer from Canada. She writes about gender, migration, human rights, and conflict, and has reported from the Middle East, Central America, and Africa. Her work has been published by The New Yorker, Harper’s, The New Republic, and the London Review of Books. She teaches investigative journalism at Sciences Po Paris.